II) The Epigraphic Evidence

A) The forms Matres – Matronae

1) Differences

The inscriptions to the Matres and Matronae fall into two main groups. On the one hand, about 150 inscriptions are dedicated to the ‘Mothers’ without specific epithets, around sixty of which mention the forms Matres or Matrae and eighty of which refer to the term Matronae, prevalent in Cisalpine Gaul (51) and Germany (25).127 Here are two instances coming from the Meseta region, in Northern Spain: Arria Nothis Matribus pro secundo v(otum) s(olvit) l(ibens) m(erito), ‘To the Matres, Arria Nothis for the second time paid her vow willingly and deservedly’, and Matrib(us) T(itus) Racilius Valerianus ex vot(o), ‘To the Matres Titus Racilius Valerianus offered this’.128 On the other hand, another hundred or so inscriptions associate their name with peculiar attributive bynames*. Indeed, about forty different epithets are known for the Matres and Matrae,129 such as, among others, the Matres Nemetiales in Grenoble (Isère),130 the Matres Britannae in Winchester (GB),131 the Matres Masanae in Cologne (Germany),132 the Matres Arsacae in Xanten (Germany),133 the Matres Brittiae in Fürstenberg and Xanten (Germany),134 or the Matres Remae in Gereonsweiler (Germany).135 As for the Matronae, around sixty different epithets have been recorded,136 such as the Matronae Ambiamarcae in Floisdorf (Germany),137 the Matronae Valabneiae in Cologne,138 the Matronae Caimine[h]ae in Euskirchen139 or the Matronae Tummaestiae in Sinzenich.140

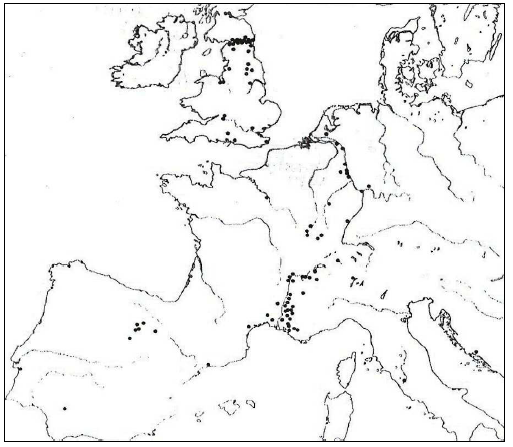

In Gaul, the terms Matres and Matrae are particularly represented in Narbonese Gaul (around 37 inscriptions), particularly in the territories of the Allobroges (10) and of the Vocontii (10), and in the north-east of Gaul, notably in the territories of the Lingones, the Aedui, the Senones and the Mediomatrici.141 Their cult is also evidenced in the territories of the Helveti and of the Sequani, even though the inscriptions are far less numerous.142 The term Matres is found in Britain, notably in the north, along Antonine’s and Hadrian’s Wall, in the east, in Chester (Cheshire), in the south-east and south, in Cirencester (Gloucestershire), Bath (Somerset) and London. It is also mentioned in various inscriptions from Germany, particularly along the Rhine, in Northern Spain, especially in the north of Meseta, and in Rome (Italy) (fig. 5).143 If the form Matres is used outside Gaul, the form Matrae seems to be confined to Gaul. As a general rule, it seems that the term Matres/Matrae is generally associated with epithets of Celtic origin. Nonetheless, it happens to be sometimes combined with a Germanic epithet, such as for the Matres Annaneptae in Xanten,144 the Matres Kannanef(ates)in Cologne,145 the Matres Suebae in Cologne and Deutz,146 theMatres Vapthiae, whose inscription was found in the Rhine,147 and the Matres Frisavae in Wissen (see below).148

As for the termMatronae, it could be viewed as the Germanic ‘counterpart’ or ‘equivalent’ of the Celtic Matres, insomuch as it ismainly confined to the Rhineland, i.e. in the regions of Jülicher, Zülpicher and the Voreifel - the area between Neuss, Bonn and Aachen -, which corresponds to the territory of the Ubii tribe.149While the Matronae are generally honoured with attributive bynames* in the Rhineland, they are venerated without specific epithets in various dedications from Cisalpine Gaul, especially in the area from Verona to the Maritime Alps and the Ligurian Riviera (fig. 6).150 As we will see, the term Matronae is generally associated with divine bynames* of Germanic origin in the Rhineland, but there are some examples of it coupled with Celtic epithets, for instance the Matronae Lubicaein Cologne151 or the Matronae Dervonnae in Milano and Brescia (Italy).152 Finally, the dedicators honouring the Matronae are sometimes of Germanic origin, such as Chamarus and Allo from Zülpich-Enzen: Matronis M(arcus) Chamari f(ilius) et Allo, ‘To the Mother Goddesses, Marcus, son of Chamarus, and Allo’.153