B) The Nursing Mothers or Nutrices

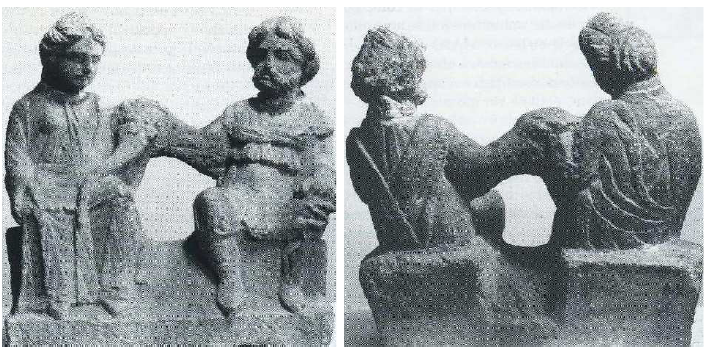

The generosity of their curves – a round abdomen and ample breasts sometimes bared - and their association with a consort or wrapped infants represent fecundity, procreation and the renewal of the human race. In the representations of divine couples, which are numerous in Autun (Saône-et-Loire), Entrains (Nièvre) and Alésia (Côte d’Or) - where around seventeen reliefs* were discovered - the goddess symbolises the concept of the ‘wife-goddess’, who marries the god to procreate.362 The deities are generally seated side by side on a throne and hold various attributes of fertility. They are sometimes turned towards each other and have affectionate gestures for one another, such as on the relief* from Alésia (fig. 14).

The theme of the Mother Goddesses nursing children is widespread in the iconography of the Matres. A high-relief* found in Vertault (Côte d’Or) shows a triad* of nursing goddesses with one breast bared, who are about to get a baby washed. 363 The first goddess holds a wrapped infant in her hands, the second one a baby’s flannel blanket and the third one a washbowl and a sponge (fig. 15). Similarly, a votive relief* discovered in Cirencester (Gloucestershire, GB) has the central goddess holding a baby in her arms, while the two other ones may have baskets of fruit or swaddling clothes for the baby on their knee (fig. 15).364 This representation is interesting, for it seems to have some indigenous peculiarities, which might differentiate it from the figurations of marked Classical character. The Mother Goddesses indeed wear their hair loose and do not wear a diadem. Other examples of such a role are the five small statuettes in white terracotta found in 1991 in a well in Auxerre (Yonne) representing seated Matres, wearing a diadem and long garments, feeding one or two infants at their breast (fig. 16).365 Similar pipe-clay figurines have been found in Britain,366 in Gaul, such as in Alésia,367 Dijon (Côte d’Or),368 and Autun (Saône-et-Loire),369 and in Germany, such as in Trier, notably in the temple dedicated to the goddess Aveta370 and in the precinct near Dhronecken.371 Those figurines are generally found in temples, houses and more particularly in sepulchral contexts.372 They may have been sorts of amulets, which women could easily carry with them because of their small size, protecting them and their children in their everyday life or during pregnancy, as well as in the afterlife when deposited in tombs. Those terra-cotta figurines were made in large numbers from the 1st c. AD to the 3rd c. AD in workshops situated for instance in Toulon-sur-Allier, Bourbon-Lancy or Autun and were easily distributed throughout Gaul and even further on account of their compact size.373

Those Gaulish and British Nursing Mother Goddesses clearly echo the cult of the Nutrices, which was significant in and around Poetovio (Slovenia) where two sanctuaries and numerous depictions, very often combined with inscriptions, were discovered. Their name is the plural of Latin nutrix, designating ‘a woman’s breast’ or ‘a wet nurse’ - cf. the verb nutricare, ‘to suckle, to nurse, to nourish, to promote the growth of (plants and animals)’.374 In Poetovio, the Nutrices are always venerated in the plural form and are often portrayed as three women, but only one of them holds and breast-feeds the baby, while the two others may be servants.375Some of the depictions are combined with inscriptions naming them, such as the one from Zgornji Breg, dating from the 2nd c. AD, which shows three women, similarly dressed, under which is engraved the following inscription: Nutricibus Aug(ustis) sacrum Aurelius Siro pro salute Aureli Primiani v.s.l.m, ‘Sacred to Augustus and to the Nutrices, Aurelius Sirus for the safety of Aurelius Primianus paid his vow willingly and deservedly’. 376 The woman in the middle is seated and feeds a baby at her left breast, while the two other ones, standing on each side, hold a patera*, a towel, a dish and an urceus* (fig. 17). It is interesting to note that the Nutrices are worshipped only at Poetovio and that a significant number of dedicators have Celtic names, such as Malia, Donnia (‘Noble’), Siro (‘Star’) and Vintumila.377 Šašel Kos maintains that these nursing goddesses were brought there by “a Celtic group which had settled the region along with other Celtic tribes when they occupied the later Regnum Noricum*”.378

There is, besides, an inscription found near Utrecht honouring the Matres Noricae, ‘The Mother Goddesses of Noricum’: Matribus Noricis Anneus Maximus mil(es) leg(ionis) I M(inerviae) v.s.l.m., which might have been offered by a soldier coming from Noricum*.379 This could be further proof of the existence of the Matres-Nutrices cult in Poetovio.380 Therefore, the Slovenian Nutrices are very similar to the British and Gaulish Nursing Mothers. They should be related to the RomanDea Nutrix (‘Wetnurse Goddess’), who was venerated alone or together with Saturnus/Frugifer or Tanit Caelestis in North Africa during the Roman period. There are examples of inscriptions dedicated to her in Lambaesis, near modern Tazoult and Azîz ben Tellis (Algeria): Nutrici Deae Aug(ustae) Sacr(um) ; Nutrici Aug(ustae) templum C. Hostilius Felix sacerdos Saturni s p. f. id. d. 381 Dea Nutrix is generally portrayed in the reliefs* breast-feeding babies or accepting children presented to her so as to gain her protection.

This nursing function is echoed in the very name of the Matres Mopates, venerated in Nimwegen (the Netherlands): Matribus Mopatibus suis M(arcus) Liberius Victor cives Nervius neg(otiator) frum(entarius) vslm.382Their epithet (*map-at-eis) is undeniably Celtic, for it is derived from Gaulish mapat-, ‘child’.383 It can be glossed as ‘The Mothers with a Child’.384 They are etymologically linked to the god Maponos (‘The Young Son’), whose name comes from Gaulish mapo-, ‘son’, ‘young boy’.385 He is venerated in various inscriptions from the north and north-west of Britain, such as in Chesterholm (2), Hadrian’s Wall (1), Corbridge (3) (Northumbria) and Ribchester (1) (Lancashire) and from Gaul, in Saint-Rémy-de-Provence (Bouches-du-Rhône), and in a Gallo-Latin inscription from Chamalières (Puy-de-Dôme).386

The Gallo-British god Maponos is an etymological forerunner of the Welsh divine hero Mabon, literally meaning ‘Youth’ or ‘Young God’ in Middle Welsh.387 The 11th-century Arthurian legend Culhwch ac Olwen recounts that Mabon son of Modron is kidnapped when he is three nights old. Culhwch goes in search of him, but it is Arthur who eventually saves him from prison in Gloucester.388 The name of Mabon’s mother, Modron, signifies ‘Mother’ and is philologically a development of the name of the Goddess of the River Marne in Gaul, Matrona (‘Mother’).389 This of course leads scholars to think that Maponos (‘Son’) was the son of Matrona (‘Mother’), like Mabon (‘Youth’) is the son of Modron (‘Mother’). A Mother–Son pattern therefore stands out from both Welsh literature and Gallo-British epigraphy. Significantly, this archetype is found again in Irish mythology. The god Oengus (‘True Vigour’), the son of the river-goddess Bóinn and the Dagda, who resides at Brugh na Bóinne (Newgrange) in County Meath, is indeed nicknamed Mac ind Óc. This form is ungrammatical and seems to have been interpreted as ‘the Son of the Youth’. It has been reasonably suggested that the true original form was different,*Maccan Óc or In Mac Óc, that is the ‘Young Boy or Son’. He is thus clearly identical to Gallo-British Maponos and Welsh Mabon.390

In this role of Nursing Mothers, the Matres appear very clearly as dispensers of fecundity and protectresses of childbirth and childhood. This is actually a universal principle found in many other ancient religions. For instance, the main role of the Egyptian Isis, the wife of Osiris, is to breast-feed Harpocrate - the name of Horus as a child.391 As for the Roman Juno, the wife of Jupiter, she is famous for presiding over childbirth and protecting women.392 She is besides nicknamed Lucina, that is ‘she who brings to the light’, when specifically fulfilling this function.