V) Triplism: a mark of Celtic tradition?

As we have seen, ‘three’ is a recurrent figure in the iconography of the Mother Goddesses. Could triplism393 be a mark of Celtic tradition, as some scholars maintain? Joseph Vendryes indeed stipulates that “triplism is a Celtic conception, according to which a person is divided into three persons, each representing one of the aspects of the total activity.”394 In Irish mythology, for example, trebling is characteristic of the divinities, who are often represented threefold or as trios. For instance, the gods who forge the weapons for the Tuatha Dé Danann in Cath Maige Tuired [‘the Second Battle of Moytirra’] are three in number. Goibniu, the smith (Old Irish goba), Luchta, the carpenter (Irish sόer), and Credne, the worker in bronze (Irish cerd), are known as na trí Dée Dána (‘the Three Gods of Craftsmanship’) in literature.395

As regards the gods, the concept of triplism is also widely found in iconography from Gaul, Britain and Ireland.396 There are indeed many representations of three-headed or three-faced gods in Gaul, such as the god from Reims, who is often equated with Mercury,397 the bearded god with prominent eyes from Langres,398 the Bronze god from near Autun,399 and those portrayed on the pots from Bavay (Nord), Jupille (Belgium) and Troisdorf (Germany).400 In Britain, reliefs* showing a three-faced stone head were discovered at the temple at Viroconium, now Wroxeter (Shrophire).401 In Ireland, in Corleck (Co. Cavan) was unearthed the famous bald round-faced tricephalos, which is a head with three identical faces, probably dating from the 1st c. AD.402

Significantly in the Irish texts, several triads of goddesses could echo the triadic groups of the Gallo-British Matres or Matronae. The Lebor Gabála Érenn [‘The Book of Invasions’] mentions that the isle of Ireland is personified by three goddesses: Ériu, Banba and Fótla.403 Similarly, the goddesses of war form a trio composed of the Mórrígain (‘Great Queen’), Badb (‘Crow’) and Macha (‘Field’), who is sometimes replaced by Nemain (‘Panic’).404 In an old glossary, Badb, Macha and the Mórrígain are said to be the three Mórrígain. This implies that the primary divine character of the trio was the Mórrígain and that she is herself envisaged as a tripled deity. This text is of great importance, for it is the only mention of the Mórrígain in triple form:

‘Badhbh, Macha ocus Mórrígain na téora Mórrígnae.Badb, Macha and Mórrígain are the three Mórrígna.405 ’

Similarly,Macha, whose name is derived from mag, ‘field’ (Magesiā > Macha), is viewed as being three in number. There are several versions in literature of the three Machas: Macha, the wife of Nemed, the Ulster Queen Macha Mong Ruadh (‘Red-haired’), daughter of Aed Rúad and wife of Cimbáeth, and Macha, the wife of Crunniuc mac Agnomain, who brings ‘debility’ to the Ulstermen.406 While the goddesses of war seem to be separate figures on account of their different roles, the three Machas might be emanations of a single deity.407 According to Georges Dumézil, whose ideas are repeated by De Vries, the three Machas are distinct figures possessing a specific role and character.408 He argues that they are the representation of the ‘functional tripartition’, reflected in most of the Celtic female triads. Indeed, the first legend presents her as a Seer (sacerdotal function), the second one as a Warrioress (war function) and the third one as a Mother-Farmer (agrarian and fertile function).409 Likewise, the daughter of the Dagda, Brigit, is a threefold goddess, for she is said in Sanas Cormaic [‘Cormac’s Glossary’], dated c. 900, to have two sisters bearing her name.410 The first Brigit possesses filidhecht, that is ‘poetry, divination and prophecy’, while the other two preside respectively over curing and smithcraft. It seems that the three Brigits are the triplication of the very same figure; triplication emphasizing and sublimating her various abilities and powers.

In Gaul, the idea of a goddess envisaged in triple form might be echoed in the name of the goddess Trittia meaning ‘Third’, related to Gaulish tritos, ‘third’.411 The goddess Trittia is mentioned in three inscriptions discovered in the Var - in Fréjus: Trittiae L(ucius) Iul(ius) Certi f(ilius) Martinus v(otum) s(olvit) l(ibens) m(erito), ‘To Trittia, Lucius Iulius Certi, son of Matinus, paid his vow willingly and deservedly’ ;412 in Pierrefeu: Trittiae M(arcus) Vibius Longus v.s.l.m., ‘To Trittia, Marcus Vibius Longus paid his vow willingly and deservedly’ ;413 and possibly in Carnoules, but the dedication is very damaged: Tritt]i(a)e Iu[lius?] Tenci[-] v.s.l.m. 414 Olmsted and Anwyl suggest that Trittia is the eponymous goddess of the city of Trets, situated near Aix-en-Provence (Bouches-du-Rhône), which Albert Grenier and Jules Toutain refute, pointing out that the inscriptions were not found precisely in the area of this town. They add that the ancient name of Trets, which is Tritis or Tretis - sometimes Trecis, then Treds - , was never written with two ‘t’s.415 The fact that the inscriptions were not very far from Trets may, however, be relevant, and the duplicated ‘t’ in Trittia may be an effect of the personification of the place. The conundrum can perhaps be best solved by considering that the town was called after the goddess Trittia, whose name in the sense of ‘third’ would more properly be written Tritia. Significantly, an inscription discovered in Duratón, Segovia, Castilla y León, in Celt-Iberia, alludes to the trinity concept of the Matres and to their potency, as their epithet Termegiste (‘the Three Almighty’) indicates: Matribus termegiste v(otum) s(olvit) l(ibens) m(erito), ‘To the Three Almighty Mothers (the dedicator) paid his vow willingly and deservedly’.416

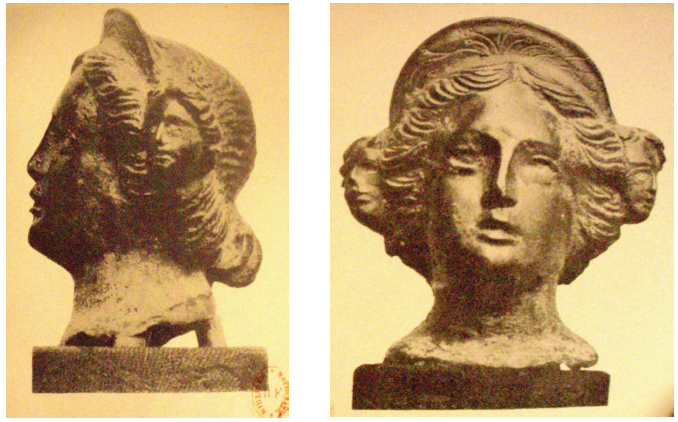

If the female triadic groups are widely represented in the iconography with the Matres, there are yet very few three-headed or three-faced goddesses. One of the few surviving examples is the small statue of a goddess in bronze discovered in 1890 in Cébazat, near Clermont-Ferrand (Puy-de-Dôme), whose head is triplicated (fig. 18).417 According to Jean-Léopold Courcelle-Seneuil, the goddess wears a diadem decorated with a plant, possibly artemisia, which was devoted to Diana.418 It is worth noting that the idea of triple-headed female supernatural beings is encountered in an 11th-century legend belonging to the lore of the hero Fionn Mac Cumhaill. In this story, entitled Finn and the Phantoms, the hero, along with his companions Caoilte and Oisín, rode to a hillock called Bairneach south of Killarney on his new black horse, won in a horse-race at Clochar (Co. Limerick).419 In the evening, they decided to stop in a mansion to have some sleep, but they rapidly realized that the place was gloomy and inhabited by weird frightening creatures, such as a grey churl, a headless man with a single eye on his chest and a hag with tri cind for a caelmuneol, i.e. ‘three heads on her scrawny neck’.420 A terrible fight broke out between the macabre supernatural beings and the three warriors which lasted until dawn, when the three creatures suddenly disappeared. The 13th-century legend Bruidhean Chéise Corainn [‘The Mansion of Keshcorran’ (Co. Sligo)] also tells of a visit of Finn mac Cumhail to the otherworld. He encountered three otherworld ugly sisters, who played sinister tricks on him and his comrade Conán Maol to punish them for hunting and sleeping on the hill of Keshcorran which belonged to their father.421 Interestingly, the concept of a threefold goddess also survived in the Welsh 12th-century Trioedd Ynys Prydein [‘Triads of the Isle of Britain’], Triad 56, which mentions that there were three Queens Gwenhwyfar at the court of Arthur:422

‘Teir Prif Riein Arthur:Gvenhvyuar verch Gvryt Gvent,

A Gvenhvyuar verch Vthyr ap Greidiavl,

A Gvenhvyuar verch Ocuran Gavr.

Three Great Queens of Arthur’s Court:

Gwennhwyfar daughter of (Cywyrd) Gwent,

and Gwenhwyfar daughter of (Gwythyr) son of Greidiawl,

and Gwenhwyfar daughter of (G)ogfran the Giant.’

According to Rachel Bromwich, Triad 56 is the only Welsh source which alludes to three Queens Gwenhwyfar; all the other texts mentioning only one Gwenhwyfar, daughter of (G)ogfran the Giant.423 In her view, the threeGwenhwyfars are a reminiscence of Welsh and Irish traditions, which offer many examples of triple goddesses.

As the iconography and literature show, triadic groups of female figures were widespread and common to Irish, British and Gaulish peoples. Threeness undeniably had a strong magico-religious dimension for the Celts, who, in triplicating their deities, dignified them and emphasized their potency and magnificence.424 Those divine trios are generally understood as the emanation and multiplication of a single deity, rather than as three distinct beings.425 They are thus seen as ‘three-in-one figures’. However, one cannot say that divine triplism is peculiar to the Celts only, for the concept of triadism is shared by many other ancient religions of Indo-European origin.

In Hinduism, for example, the trimūrti, meaning ‘trimorphic’ or ‘three forms’, is the triple aspect of the supreme being, symbolized by a triad* of primordial gods, that is Brahmā, the creator of the world, Visnu, the preserver of nature, and Shiva, who destroys the world at the end of each age.426 In Slavic mythology too, the primary god is called Triglav, literally ‘Three-Headed’.427 He represents the unity of three gods, called Svarog, Perùn and Dažbog - later Veles or Svetovid. He also reigns over three realms. His first head indeed presides over the Sky, his second head over the Earth and the third one over the Under-World, symbolizing thus the three powers of the universe: expansion, retention and balance. A three-sided god governing the same three worlds is also found in the religion of the Toba-Bataks of Sumatra in Indonesia,428 while in the religion of ancient Iran, triads of gods are also found, such as Mithra, Ahura Mazdâh and Anâhita, or Zervân, Ohrmizd and Mihr.429

Three-fold goddesses are also widely represented in Classical mythology. As we will see, the goddesses of Fate, the Roman Fatae and Greek Moirai are generally represented three in number. Similarly, the Nymphs, who are the embodiment of Nature, appear as a trio of goddesses. Such is also the case of the Greek Graces, who are generally depicted as three women symbolizing beauty, gentleness and friendship, sometimes bearing the names of Aglaia, Charis and Pasithea.430 The Greek goddess of the dead, Hecate (‘she who has power far off’), is also represented as a three-faced or three-bodied figure in the iconography.431 She is, besides, usually called ‘the Triple Hecate’. Moreover, the terrifying snake-haired and fanged Gorgons are three sisters, called Medusa (‘Ruler’), Stheno (‘Strength’) and Euryale (‘Wide-Leaping’), who turn into stone whoever meets their eyes.432 They are related to the three grey-hairedGraiae (‘Old Women’), named Enyo (‘Furious’), Pemphredo (‘Waspish’) and Deino (‘Dreadful’), who live in Atlas’ cave and possess a single eye and a single tooth which they lend to each other.433 Even though the Muses are generally said to be nine in number, they were originally envisaged as a trio of goddesses, presiding over music, dance, fine arts and above all poetry.434 On Mount Helicon, in the region of Thespiai, in Boeotia (Greece), the Muses Melete (‘Practice’), Mneme (‘Memory’) and Aoede (‘Song’) inhabit two springs, the Aganippe and the Hippocrene, while in Sicyone (Peloponnese) and in Delphi they personify the three strings of the ancient lyre, as their respective names Nete (‘Bottom’), Mese (‘Middle’) and Hypate (‘Top’) show.435

From all of this, it follows that triplism is a typical characteristic of Celtic deities but is not specifically a mark of Celticity, threefold dieties being found in many other ancient mythologies. Divine triplism actually goes back to Indo-European times, but it is significant that it survived so strongly in Welsh and Irish literatures and in Gallo-British iconography.