C) The Nymphs

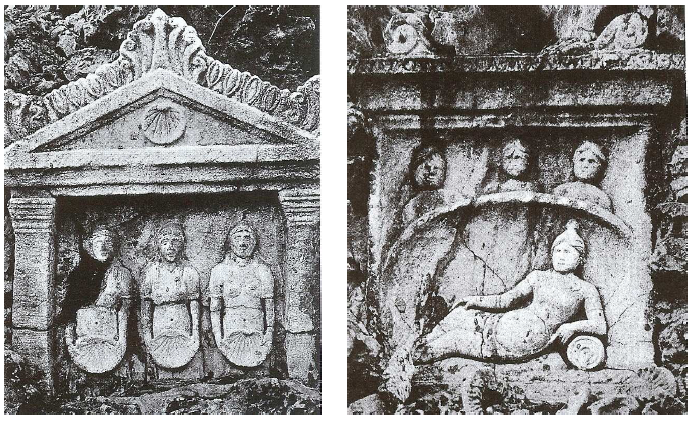

From the Roman invasion, particularly in the south and south-east of Gaul, the cult of the ‘Mothers’ seems to have often been replaced by the Greco-Roman Nymphs, whose name in Greek nýmphai and in Latin nymphae means ‘young woman’, ‘bride’.490 In Classical mythology, the Nymphs are youthful and beautiful female Nature deities who inhabit the sea, rivers, springs, trees, mountains, and generally appear in groups.491 The association between the ‘Mothers’ and the Nymphs was made especially in the context of healing waters and sanctuaries, for the Nymphs are usually remembered as female water-spirits and represented in the Greco-Roman iconography as half-naked or naked women, generally appearing three in number.492 An altar from the springs of Allègre-les-Fumades or Fonts-Belles (Gard) combines an inscription Nymphis Casunia Quintina v.[s . l.] m., ‘To the Nymphs, Casunia Quintina paid her vow willingly and deservedly’, with a depiction of three Nymphs, who stand half-naked, holding a shell in front of them. Their hair is loose and they wear bracelets around their arms, above the elbow (fig. 21).493 On the same site was discovered another altar having a goddess, lying on an urn, surmounted by three busts of Nymphs (fig. 21). The figuration goes with the following inscription: Nymp(his) Quintina Maximi f(ilia) v.s.l.m., ‘To the Nymphs, Quintina daughter of Maximus paid her vow willingly and deservedly’.494

Only one dedication associates the terms Matres and Nymphs. It is engraved on a votive altar and was discovered in a place known as ‘Val des Nymphes’, situated east of the village of La Garde-Adhémar (Drôme), in the territory of the Tricastini: Matris Nymphis [...o...]ernus Ply[ca]rpus v(otum) s(olvit) l(ibens) m(erito), ‘To the Mothers Nymphs, [...o...]ernus Polycarpus paid his vow willingly and deservedly’.495 The altar can be seen at the entrance of the church of Saint-Michel de la Garde-Adhémar (fig. 22).

The Nymphs are venerated on their own in numerous inscriptions from the Continent and Britain. In Britain, they are for instance venerated at the foot of Croy Hill (Dunbarton), at Greta Bridge fort (Rokeby, Yorkshire), in Chester (Cheshire), in Risingham (Northumbria) and in Carvoran (Northumbria): Deabus Nymphis Vetti[a] Mansueta e[t] Claudia Turi[a]nilla fil(ia) v(otum) s(oluerunt) l(ibentes) [m(erito)], ‘To the Goddesses Nymphs Vettia Mansueta and Claudia Turianilla, her daughter, willingly and deservedly fulfilled their vow’.496 In Gaul, they are more specifically honoured in Narbonese Gaul, where more than thirty dedications to the Nymphs have been discovered,497 notably in St-Saturnin d’Apt (Vaucluse),498 Vaison-la-Romaine (Vaucluse),499 Carpentras (Vaucluse),500Allègre-les-Fumades (Gard),501 Uzès (Gard),502 Nîmes (Gard),503 Montpellier (Hérault),504 Aix-en-Provence (Bouches-du-Rhône).505 This can be explained by the fact that there are many curative springs in the area. They are also worshipped in other areas from Gaul and Germany, such as in Auch (Gers),506 Lyons (Rhône),507 Langres (Haute-Marne),508 Tongres (Belgium),509 Miltenberg (Germany),510 Zingsheim (Germany),511 Dormagen (Germany),512 etc.513

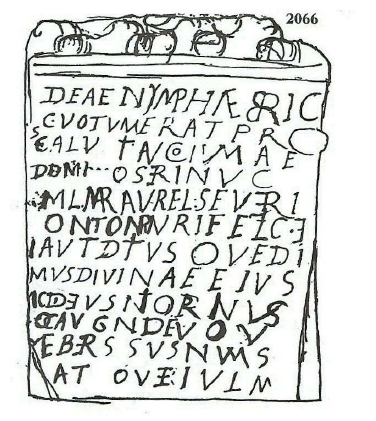

The Nymphs are generally anonymous, but a few inscriptions from Britain and Gaul impart them divine titles, some of which are definitely Celtic, while others are not. The Nymphs are for instance called ‘Percernes’ in a single dedication from Vaison-la-Romaine: Nymphis Aug(ustis) Percernibus T(itus) Gingtius Dionysius ex voto, ‘To the August Nymphs Percernes Titus Gingtius Dionysius offered this’.514 Their name might be derived from Indo-European *perkw-, ‘oak’, which became *kw-erkw-, in Common Celtic.515 Lambert yet specifies that Percernibus is likely to be Ligurian rather than Celtic.516 As for the goddess Brigantia, who undeniably bears a Celtic name,517 she is surprisingly called deae Nymphae (dative sing.) on an altar discovered near Hadrian’s Wall (GB), although she is generally associated with war deities, such as Victoria or Caelestis.518 The inscription is the following (fig. 23):

‘Deae Nymphae Brig(antiae) quod [uo]uerat pro sal[ute et incolumitate] dom(ini) nostr(i) Inuic(ti) imp(eratoris) M(arci) Aurel(i) Seueri Antonini Pii Felic[i]s Aug(usti) totiusque domus diuinae eius M(arcus) Cocceius Nigrinus [pr]oc(urator) Aug(usti) n(ostri) deuo[tissim]us num[ini maies]tatique eius u(otum) s(oluit) l(ibens) m(erito)This offering to the goddess-nymph Brigantia, which he had vowed for the welfare and safety of our Lord the Invicible Emperor Marcus Aurelius Severus Antoninus Pius Felix Augustus and of his whole Divine House, Marcus Cocceius Nigrinus, procurator of our Emperor and most devoted to his deity and majesty, gladly, willingly, and deservedly fulfilled.519 ’

The goddess Coventina, known by fourteen inscriptions at the holy well of Carrawburgh, (South Northumbria, GB), is also called Nymphae (dative sing.)in two dedications.520The origin of her name is not yet determined with certainty. She might be a Celtic goddess or not. Another famous example illustrating this association between the Mothers and the Nymphae is that of the Nymphs Griselicae, who presided over the healing spring at Gréoux-les-Bains (Alpes-de-Haute-Provence), but the Celticity of their name is however unlikely. One can admit at least the Celticity of the suffix ika- in Griselica. As a consequence, even though the place-name (or god name) Grisel- is not Celtic, the derived form Griselica may have been invented by the Celts. The inscription is the following: [Annia M(arci) ---] fil(ia) Faustina T(iti) Vitrasi(i) Poll[i]onis co(n)s(ulis). II. Praet(oris) [q]uaest(oris) Imp(eratoris) pontif(icis), [proc]o(n)s(ulis) Asiae uxor Nymphis Griselicis, ‘Annia Faustina, daughter of Marcus, [...] wife of Titus Vitrasius Pollion, consul for the second time, praetor, quaestor of the Emperor, pontiff, proconsul of Asia, to the Nymphs Griselicae’ (fig. 24).521

The Nymphs are also called ‘Volpiniae’ in an inscription from Tönnistein (Germany), a term which does not seem to be of Celtic origin: […?] et Nimpis Volpinis Cassius Gracil[i]s Veteranu[s] v.s.l.m., ‘[...] and to the Nymphs Volpiniae, Cassius Gracillis Veteranus paid his vow willingly and deservedly’.522 Finally, in a very damaged inscription from Gonsenheim (Germany), the Nymphs are termed ‘Laurentes’: [Ny]mphis Lauren[tibus], ‘To the Nymphs Laurentes’.523 Olmsted suggests that the Nymphs Laurentes are the protective Celtic goddesses of a local spring near Gonsenheim and that their name must refer to a toponym*,524but in this he is mistaken, for a reference to the Nymphs Laurentes is found in Virgil’s Aeneid.525 They are indeed invoked in a prayer by Aeneas when he sails to Pallenteum (Mount Palatine, in Rome):

‘Nymphae, Laurentes Nymphae, genus amnibus unde est, tuque, o Thybri tuo genitor cum flumine sancto,accipite Aenean et tandem arcete periclis.526

Nymphs, Laurentine Nymphs, who give birth to rivers come, and you, O father Thybris with your hallowed stream, receive Aeneas and guard him at last from danger.527 ’

Their epithet actually refers to the territory of the people of the Laurentines, which was situated south of ancient Ostia, in Latium, at the mouth of the Tiber, in Central Italy. They must have been the water spirit inhabiting the rivers of that particular area and are therefore Latin.