C) The Land as the Body of the Goddess

In Irish literary tradition, other goddesses have marked agricultural features and bear names referring to the earth. Legends tell of their death and their burial in the land, which then became called after them. From that moment on, earth and goddess were as one and parts of her body could be seen in the landscape.

The Irish goddess Clidna is etymologically related to the land, for she has a name meaning ‘the Territorial One’.647 Moreover, she is associated with Cúan Dor (‘Harbour of Gold’), the bay of Glandore, in Co. Cork, and remembered as Tonn Chlíodhna (‘Clíodhna’s Wave’), because she was drowned there. She will be studied in more detail in Chapter 4.

Another noteworthy example is the queen-goddess Tailtiu, who was married to the last Fir Bolg King Eochaid mac Eirc and is sometimes said to be the foster mother of the powerful Lugh Lámfhota.648 De Vries explains that Tailtiu’s name was originally *talantiu, cognate with Irish talam, ‘earth’, from IE *tel, ‘flat, flat floor’.649 Tailtiu thus means ‘Earth’ or ‘Plain’. In the Metrical Dindshenchas, she is said to be the daughter of Mag Mór (‘Great Field’) and to have cleared the forests and dug the plain of Brega, situated between the Boyne and the Liffey (mostly Co. Meath). This is indicative of a significant agrarian character. The legend tells of her death, due to exhaustion, and of her interment in a field which became called after her: Mag Tailtiu (‘Plain of Tailtiu’), now Teltown, in County Meath. On her deathbed, she asked to have a feast held in her honour each year. It is known as Óenach Tailten (‘Tailtiu Fair or Assembly’). The legend is the following:

‘A chóemu críche Cuind chain éitsid bic ar bennachtain; co n-écius duíb senchas sen, suidigthe óenaig Thalten.Trí chét blíadan, fodagaib, teora blíadna do blíadnaib co gein Críst, coistid rissein, ón chét-óenuch i Taltein.

Taltiu ingen Magmóir maill, ben Echach gairb maic Dúach daill, tánic sund ria slúag Fer mBolg co Caill Cúan iar cath chomard. […]

Mór in mod dorigned sin al-los túagi la Taltin athnúd achaid don chaill chóir la Taltin ingin Magmóir.

Ó thopacht aicce in chaill chain cona frémaib as talmain, ria cind blíadna ba Bregmag, ba mag scothach scoth-shemrach.

Scaílis a cride 'na curp iarna rige fo ríg-brutt; fír nach follán gnúis fri gúal, ní ar fheda ná fhid-úal.

Fota a cuma, fota a cur i tám Thalten iar trom-thur; dollotar fir, diamboí i cacht, inse h-Érend fria h-edacht.

Roráid-si riu 'na galur, ciarb énairt nírb amlabur, ara n-derntais, díchra in mod, cluiche caíntech dia caíniod.

Im kalaind Auguist atbath, día lúain, Loga Lugnasad; imman lecht ón lúan ille prím-óenach h-Erend áine.

Dorairngert fáitsine fír Taltiu tóeb-gel ina tír, airet nosfaímad cech flaith ná biad h-Ériu cen óg-naith.

O nobles of the land of comely Conn, hearken a while for a blessing, till I tell you the legend of the elders of the ordering of Tailtiu's Fair!

Three hundred years and three it covers, from the first Fair at Tailtiu to the birth of Christ, hearken!

Tailtiu, daughter of gentle Magmor, wife of Eochu Garb son of Dui Dall, came hither leading the Fir Bolg host to Caill Chuan, after high battle.

Great that deed that was done with the axe's help by Tailtiu, the reclaiming of meadowland from the even wood by Tailtiu daughter of Magmor.

When the fair wood was cut down by her, roots and all, out of the ground, before the year's end it became Bregmag, it became a plain blossoming with clover.

Her heart burst in her body from the strain beneath her royal vest; not wholesome, truly, is a face like the coal, for the sake of woods or pride of timber.

Long was the sorrow, long the weariness of Tailtiu, in sickness after heavy toil; the men of the island of Erin to whom she was in bondage came to receive her last behest.

She told them in her sickness (feeble she was but not speechless) that they should hold funeral games to lament her—zealous the deed.

About the Calends of August she died, on a Monday, on the Lugnasad of Lug; round her grave from that Monday forth is held the chief Fair of noble Erin.

White-sided Tailtiu uttered in her land a true prophecy, that so long as every prince should accept her, Erin should not be without perfect song.650 ’

Likewise, the goddess Macha is closely related to the land, agriculture and fertility, for her name can be glossed as ‘a marked portion of land’.651 In Irish, the singular word macha, plural machada, signifies ‘an enclosure for milking cows, a milking yard’, while machaire is ‘a large field or plain’.652 M. J. Arthurs relates her name to Irish mag, Gaulish magos, ‘field’ and supposes that the original form of Macha is *Magosia (‘Plain’, ‘Field’ or ‘Earth’).653

A poem of the Metrical Dindshenchas, entitled Ard Macha [‘The High Place of Macha’], relates that the first Macha, the wife of the third invader of Ireland, Nemed, was murdered and then buried in one of the twelve plains which her husband had cleared:

‘In mag imríadat ar n-eich, do réir Fíadat co fír-breith, and roclass fo thacha thig in mass, Macha ben Nemid.Nemed riana bail ear blaid dá sé maige romór-slaid: ba díb in mag-sa, is maith lemm, dara rag-sa im réim rothenn.

Macha, robráena cach mbúaid, ingen ard Áeda arm-rúaid, sund roadnacht badb na mberg, dia rosmarb Rechtaid rig-derg.

In the plain where our horsemen ride, there, by the will of the right-judging Lord, was buried in fair seclusion a lovely woman, Macha wife of Nemed.

Twice six plains did Nemed clear before his home, to win renown; of these was this plain, to my joy, across which I shall wend my steady way.

Macha, who diffused all excellences, the noble daughter of red-weaponed Aed, the raven of the raids, was buried here when Rechtaid Red-Wrist slew her.654 ’

The Lebor Gabála Érenn [‘The Book of Invasions’] gives the same account and indicates that her name was given to the plain where she was buried: Ard Macha, modern Ard Mhacha, anglicised Armagh, understood by mediaeval writers as ‘The High Place of the goddess Macha’. Actually, this place name would have originally meant no more than ‘the high point of the plain’, with ard signifying ‘height’, ‘raised point’ and macha, ‘plain’. The reversion to goddess-imagery in the context of such a placename is significant. Such imagery was enduring:

‘Acht is muchu atbath Macha ben Nemid oldās Andind, .i. in dara lāithe dēc īar tiachtain dōib in Hērinn atbath Macha, 7 issī cēt marb Ērenn do muintir Nemid. Ocus is ūaithe ainmnigter Ard Macha.But Macha wife of Nemed died earlier then Annind; in the twelfth year after they came into Ireland Macha died, and hers is the first death of the people of Nemed. And from her is Ard Macha named.655 ’

In those two legends, Macha is clearly associated with the land and agriculture. And yet, Dumézil, who relies on the Edinburgh Dinnshenchas, asserts that Macha does not have an agrarian character. According to him, she has an obvious function of ‘seer’.656 If this attribute is indeed plainly described in the poem, it seems yet difficult to dismiss the idea that Macha is linked to the land. It must be borne in mind that the Edinburgh Dinnshenchas date from the 15th c., which means they are later than the Metrical Dindshenchas. Despite their late date, the Edinburgh Dinnshenchas remain interesting, for they speak of the three Machas and relate how they were killed and buried in a land which was then named after them. The first part on Macha, wife of Nemed, is the same as the one related in the Metrical Dindshenchas and the Lebor Gabála Érenn [‘The Book of Invasions’], apart from the function of foreseeing attributed to her. The second part of the poem depicts how Macha Mong Ruadh (‘Red-haired’) was slain and interred in the field now bearing her name: Mag Macha (‘the Plain of Macha’), surrounding Emain Macha. Finally, the third part tells of Macha, wife of Crunniuc mac Agnomain, who engendered the debility on the Ulstermen and was buried in a place known as Ard Macha (‘Macha’s Height’). The poem is the following:

‘Ard Macha, cid dia ta? Ni ansa.Macha ben Nemidh meic Agnomain atbath ann, 7 ba he in dara magh deg roslecht la Nemhead, 7 do breatha dia mhnai go mbeith a ainm uasa, 7 is i adchonnairc i n-aislinge foda reimhe a techt ina ndernad do ulc im Thain bho Cuailngi ina cotludh tarfas di uile ann rocesad do ulc and do droibhelaib 7 do midhrennaib, go ro mhuidh a cridhe inti. Unde Ard Macha.

Atchonnairc Macha marglic tri fhis,

ratha na raidmid,

tuirthechta trimsa Cuailghne

fa gnim ndimsa nimuaibre.

Nó Macha ingen Ædha Ruaidh meic Baduirnn, is le rotoirneadh Eomuin Macha, 7 is and roadnacht día ros-marbh Rechtaid Rígderg, is dia gubhu rognídh ænach Macha. Unde Macha magh.

Ailiter, Macha dano bean Cruind meic Agnomhain doriacht ann do comrith ann ri heocho Conchobair, ar atbert a fear ba luathe a bean inaid na heocho. Amlaidh dano bai in bean sin, inbhadach, go ro chuindigh cairde go ro thæd abru, 7 ní tugadh di, 7 dogní in comhrith iarum 7 ba luaithiamh si, 7 o roshiacht cend in chede berid mac 7 ingin, Fir 7 Fíal a n-anmann, 7 atbert go mbeidis Ulaidh fo cheas oitedh in gach uair dos-figead eigin, conid de baí in cheas for Ultu fri re nomaide o re Conchobhair go flaith Mail meic Rocraide, 7 adberar ba si Grian Banchure ingean Midhir Bri Léith, 7 adbeb iar suidhiu 7 focreas a fert i nArd Macha, 7 focer a gubha, 7 roclannad a lía. Unde Ard Macha.

Ard Macha, whence is it? Not hard (to say).

Macha, wife of Nemed, son of Agnoman, died there, and it was the twelfth plain which was cleared by Nemed, and it was bestowed on his wife that her name might be over it, and ’tis she that saw in a dream, long before it came to pass, all the evil that was done in the Driving of the Kine of Cualnge. In her sleep there was shown to her all the evil that was suffered therein, and the hardships and the wicked quarrels: so that her heart broke in her. Whence Ard Macha, ‘Macha’s Height.’

Macha, the very shrewd, beheld

Through a vision — graces which we say not —

Descriptions of the times (?) of Cualnge —

’Twas a deed of pride, not of boasting.

Or, Macha, daughter of Aed the Red, son of Badurn: ’tis by her that Emain Macha was marked out, and there she was buried when Rechtaid Red-arm killed her. To lament her Oenach Macha, ‘Macha’s Assembly,’ was held. Whence Macha Magh.

Aliter. Macha, now, wife of Crunn, son of Agnoman, came there to run against the horses of King Conor. For her husband had declared that his wife was swifter than the horses. Thus then was that woman pregnant: so she asked a respite till her womb had fallen, and this was not granted to her. So then she ran the race, and she was the swiftest. And when she reached the end of the green she brings forth a boy and a girl — Fír and Fíal were their names — and she said that the Ulaid would abide under debility of childbed whensoever need should befall them. So thence was the debility, on the Ulaid for the space of five days and four nights (at a time) from the era of Conor to the reign of Mál, son of Rochraide (A.D. 107). And ’tis said that she was Grian Banchure, ‘the Sun of Womanfolk,’ daughter of Midir of Brí Léith. And after this she died, and her tomb was raised on Ard Macha, and her lamentation was made, and her pillar-stone was planted. Whence is Ard Macha, ‘Macha’s Height.’657 ’

It is interesting to note that Macha is etymologically related to epithets of Gaulish Mother Goddesses. The byname* of the Matres Mageiae, mentioned in an inscription from Anduze (Gard), may be derived from Celtic *magos, cognate withOld Irish mag, gen. maige, meaning ‘field’, ‘plain’.658 Could the Matres Mageiae be understood as ‘The Mother Goddesses of the Field/Plain’? The inscription is the following: Q. Caecilius Cornutus Matris Mageis v(otum) s(olvit) [l(ibens) m(erito)], ‘To the Mothers Mageiae, Q. Caecilius Cornutus paid his vow willingly and deservedly’. The dedicator bears the tria nomina of Roman citizens.

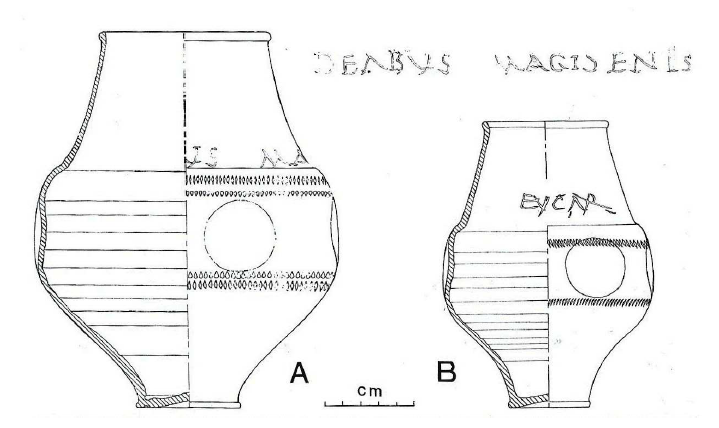

This root is also found in the name of the goddesses Magiseniae, known from some graffiti engraved on a goblet discovered in Strasbourg (Bas-Rhin): Deabus Magiseniis, ‘To the Goddesses Magiseniae’ (fig. 2).659 Their name seems to be composed of Gaulish magi-, ‘broad’, ‘big’, ‘vast’ (*magos ‘field’) and seno-, seni-, sena-, ‘old’, ‘ancient’.660 The Magiseniae might therefore mean something like ‘The Broad Ancient Ones’ or ‘The Old Fields’. From this etymology*, it follows that the Magiseniae were land-goddesses and ancestresses; an aspect reflected in the story of Irish Banba, who simultaneously appears as the ancestress of the divine race and the embodiment of the isle itself. On account of the similarity of the names, some scholars have assumed that the Magiseniae were the consorts of Hercules Magusanus/Magusenus of the military camps, venerated in 22 inscriptions from Romania, Germany, Belgium, the Netherlands, Britain and Rome.661 This is actually not the case, for his epithet is to be related to Celtic magus, ‘servant’ and not to *magos, ‘field’. Magusenus, composed of magus and senos, is ‘the Old Servant’.662

The concept of the land as the goddess’s body is mirrored in accounts specifying that Danu’s and the Mórrígain’s breasts are eminences in Co. Kerry and Co. Meath. Danu, the mother and ancestress of the Tuatha Dé Danann, brings prosperity to the province of Munster. The Lebor Gabála Érenn [‘The Book of Invasions’],663 Sanas Cormaic [‘Cormac’s Glossary’]664 and Cóir Anmann [‘The Fitness of Names’]665 mention that two hills in Co. Kerry are called Dá Chích Anann, that is ‘The Paps of Anu’. These two hills, situated 10 miles east of Killarney, near Clonkeen, have the shape of two breasts and cairn burials at their summit (fig. 3 and 4):

‘Nó Muma .i. mó a hana nás ana cach coigidh aili a nEirinn, ar is innti nó adhradh bandía in tsónusa .i. Ana a hainm-sein, 7 is uaithi sidhe isberar Da Chigh Anann ós Luachair Degad.Or Muma, that is mó, ‘greater’ its ána, ‘wealth’ than the wealth of every other province in Erin; for in it was worshipped the goddess of prosperity, whose name was Ána, and from her are named the Two Paps of Ána over Luachair Degad.666 ’

The Mórrígain’s body also shapes the landscape, for two small mounts, near Newgrange, in Co. Meath, are named after her: Dá Chích na Mórrígana, ‘The Paps of the Mórrígain’.667 In the Metrical Dindshenchas, they are alluded to as “the two Paps of the King [Dagda]’s consort”, that is the Mórrígain:

‘[…] Fégaid Dá Cích rígnai ind ríg / sund iar síd fri síd blai síar: / áit rogénair Cermait coem / fégaid for róen, ní céim cían […].[…] Behold the two Paps of the king’s consort[i.e. the Mórrígain]/ here beyond the mound west of the fairy mansion: / the spot where Cermait the fair was born, / behold it on the way, not a far step […].668 ’

It is worth noting that the Mórrígain is equated with Anu/Danu in the Lebor Gabála Érenn [‘The Book of Invasions’]. This tends to prove that the Mórrígain, who is part of the trio of war-goddesses, was originally a land-goddess possessing fertility and nurturing aspects:

‘Badb 7 Macha 7 Annan .i. Mórrígan .i. diatat Da Chich Anann i l-Luachair, tri ingena Ernbais na bantuathaige 7 de bl aithmn.Badb and Macha and Anann [i.e. the Morrigu] of whom are the Two Paps of Ana in Luachair, the three daughters of Ernmas the she-husbandman i.e. [….?]669

Tri ingena aile dana oc Ernmais, .i. Badb 7 Macha 7 Mórrigu, .i. Anand a hainmside.

Ernmas had other three daughters, Badb and Macha and Morrigu, whose name was Anand.670

In Mor-rigu, ingen Delbaith mathair na mac aile Dealbaith .i. Brian 7 Iucharba 7 Iuchair: 7 is dia forainm Danand o builead Da Chich Anann for Luachair, 7 o builed Tuatha De Danann.

The Morrigu, daughter of Delbaeth, was mother of the other sons of Delbaeth, Brian, Iucharba, and Iuchair: and it is from her additional name ‘Danann’ the Paps of Ana in Luachair are called, as well as the Tuatha De Danann.671 ’

The Lebor Gabála Érenn [‘The Book of Invasions’] also stipulates that the Mórrígain and Macha are identical. Fertility is also personified by their mother Ernmas, who is a ‘she-farmer’, like Be Chuille and Dianann:

‘Badb 7 Macha .i. in Mórrígan 7 Anann .i. diata da chích Anann .i. l-Luachair trī ingena Ernbais na bantūathige.Badb and Macha [i.e. the Morrigu], and Anann of whom are the Two Paps of Anna in Luachair were the three daughters of Ernmas the she-farmer.

Bē Chuille 7 Dianand na dī ban-tūathig.

Be Chuille and Dianann were the two she-farmers.672 ’

The Mórrígain is clearly associated with the land and agriculture in an early text, entitled Compert Con Culainn [‘The Conception of Cú Culainn’], dating from the beginning of the 8th c. This legend describes her ploughing a piece of land, which her husband, the Dagda, offered to her. This meadow is called after her: Gort-na-Morrigna (‘Mórrígain’s Field’). It is now identified with Óchtar nÉdmainn (‘Top of Edmand’), situated on the border of Co. Armagh and Co. Louth.673 The text is the following:

‘In Gort na Mórrígnae asrubart is Óchtar nÉdmainn insin. Dobert in Dagdae don Mórrígain in ferann sin 7 ro aired leesi é íarom.The ploughing/field of the Great Queen which he said is Óchtar nÉdmainn. The Dagda gave to the Great Queen that land and it was ploughed by her after that.674 ’

Finally, the pattern of goddess’s body shaping the landscape is mirrored in an in-tale* of Compert Con Culainn [‘The Conception of Cú Culainn’], entitled Tochmarc Emire [‘The Wooing of Emer’].675 Cú Chulainn describes his journey to his lover Eimhear and gives onomastic* information concerning the places he passed through. He recounts then the story of the River Boyne, flowing to the north of Dublin, and explains how the goddess Bóinn was drowned in the river after making trial of the enchanted well of her husband Nechtan (see Chapter 4). What is particularly interesting in this legend is that parts of the river are clearly described as body-parts of the goddess. A portion of the river is her forearm and her calf, while another is her neck and another her marrow:

‘For Smiur mná Fedelmai asrubrad .i. Bóann insin. Is de atá Bóann fuirri .i. Bóann ben Necthain meic Labrada luid do choimét in topair díamair baí i n-irlainn in dúine la trí deogbairiu Nechtain .i. Flesc 7 Lesc 7 Lúam. 7 ní ticed nech cen aithis ón topur mani tísed na deogbairiu. Luid in rígan la húaill 7 duimmus dochum in topair 7 asbert ná raibhe ní no collfed a deilb nó dobérad aithis fuirri. Tánic túaithbél in topair do airiugud a cumachtai. Ro memdatar íarom teora tonna tairis cor róemaid a dí slíassait 7 a dessláim 7 a lethsúil. Rethissi dano for imgabáil na haithise sin asin tsíth co ticed muir. Cach ní ro reithsi, ro reith in topar ina diaid. Segais a ainm isin tsíth, sruth Segsa ón tsíth co Linn Mochai, Rig Mná Núadat 7 Colptha Mná Núadat íar sin, Bóann i mMidi, Mannchuing Arcait í ó Findaib co Tromaib, Smiur Mná Fedelmai ó Tromaib co muir.On the Marrow of Fedela’s wife as said i.e. Boánn she was. She is called Boánn from this, i.e. Boánn the wife of Nechtan, son of Labhraidh, who went to observe the mysterious well that was at the verge of the fortress along with the three cupbearers of Nechtan, i.e. Flesc and Lesc and Lúann. And nobody used to come without a blemish from that well except for the cupbearers. The queen went with ostentation and pride to the well, and she said that there was nothing which would damage her appearance or would cause blemish to her. She came left-handwise around the well to feel its power. Then three waves rose up from it, so that her two sides and her right hand and one of her eyes were fractured. She ran then to avoid that blemishing, from the mound until she reached the sea. Wherever she ran, the well ran after her. Segais was its name in the mound – the stream of Segais from the Pond of Mochae, the Forearm of Nuadhu’s wife and the calf of Nuadhu’s wife following that. Boánn in Midhe (Middle), she is the Mannchuing (neck) of Silver from the [rivers] Finn to the [rivers] From. It is the Marrow of Fedhelm’s wife676 from the [rivers] From to the sea.677 ’

This tale undeniably predates the 10th c., for Tochmac Emire [‘The Wooing of Emer’] was continually revised from the 8th c. to the 10th c. The same story is related in the first version of a poem, entitled Bóand, published in the Metrical Dindshenchas (see Chapter 4).678