2) Inscriptions

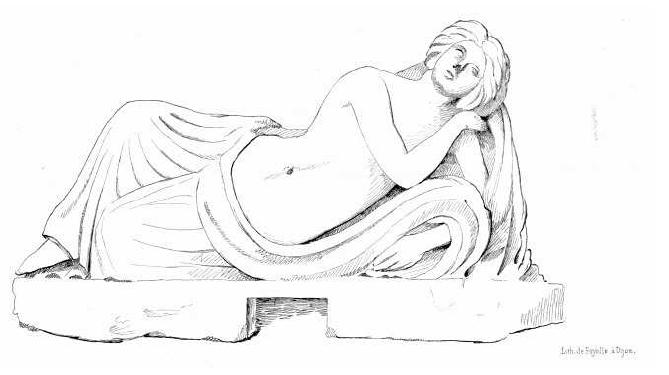

Pierre Lambrechts saw in Rosmerta a mere female duplication of the god Mercurius, explaining that she did not have any peculiar functions or roles, apart from being the consort of the god.781 This is actually incorrect to say, since recent archaeological evidence has proved that Rosmerta was worshipped in her own right. This is the case in five inscriptions, two of which are combined with a figuration. Therefore, it can be affirmed that Rosmerta fulfilled far more important functions in ancient times than being the mere partner of a Gallo-Roman god. In Gissey-le-Vieil (Côte d’Or), in the territory of the Aedui, she was honoured in a now lost inscription: Aug(usto) sa[c(rum)] Deae Rosm[er]tae Cne(ius) Cominius Candidus et Apronia Avitilla v(otum) s(olve)runt l(ibentes) m(erito), ‘Sacred to the August Goddess Rosmerta, Cneius Cominius Candidus et Apronia Avitilla paid their vow willingly and deservedly’ (fig. 12).782 The two dedicators may be husband and wife. While the man is a Roman citizen, for he bears the tria nomina, the woman’s first name Apronia is a patronymic Latin name and her second name Avitilla is Celtic – it is possibly based on avi-, ‘desir’.783 On account of the use of the formula Dea, the inscription was not prior to the mid-2nd c. AD.784 Dr Morelot, who studied the altar in 1843, assumed that Rosmerta was a topical* deity whose cult was attached to the curative waters of Gissey.785 According to him, Gissey is a Celtic name meaning ‘place filled with water’, with Celtic gi, ‘water and cey, ‘full of’. In the same area, a statue of a half-naked woman lying down, probably dating from the end of the 2nd c. AD or the beginning of the 3rd c., was discovered. She may be the personification of the waters of Gissey, for river- and spring-goddesses are very often depicted in such a position, wearing only a cloth around their hips (fig. 13).786 It may be thus inferred that the worship of Rosmerta in this locality was connected to the thermal waters of Gissey-le-Vieil.787

Rosmerta is also invoked by herself in a dedication unearthed in the locality of ‘La plaine au-dessus des Bois’, in Dompierre-sur-Authie (Somme), situated in the territory of the Ambiani. The inscription, engraved on a silver band, belonging to the wooden pedestal of a statuette, was found in 1989 during the excavations of a sanctuary, dating from the end of the 1st c. AD, composed of a fanum* and open-air areas where deposits of offerings were made. This inscription reads: Rosmert(ae) Aug(ustae) Exstipibus, ‘To the August Rosmerta Exstipibus (offered this)’ (fig. 14).788

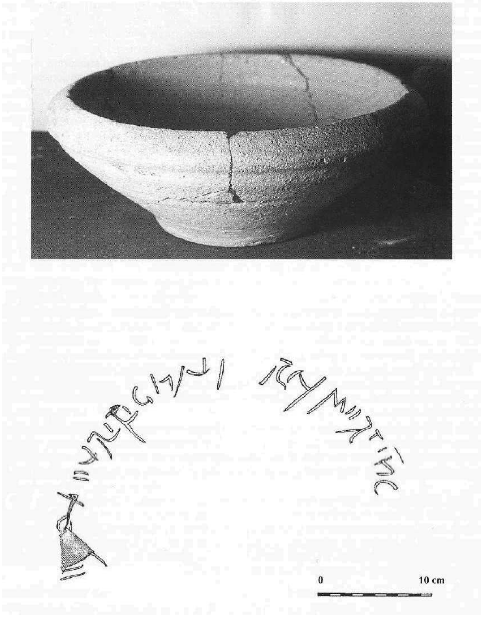

Furthermore, an early inscription in Gaulish language and Latin lettering, engraved along the inside brim of an earthenware vessel unearthed in Lezoux (Puy-de-Dôme), comprises the divine names Rosmerta and Rigani (fig. 15). The ‘Terrine de Lezoux’ was discovered in 1974 on the site of the Neolithic and Proto-historic necropolis ‘Chassagne’, also called ‘des Religieuses’, excavated between 1972 and 1976 in the ‘Pré Tardy’, which is situated west of Lezoux (Puy-de-Dôme), in the territory of the Arverni. It was found in a funerary well dating to the time of Tiberius (1st half of the 1st c. AD).789 The RIG II.2 gives the following transcription:

‘e[..]o i euri rigani rosmertiac.790 ’Several interpretations of this inscription have been proposed. On the one hand, Rigani and Rosmerta could be the name of two different goddesses. Rigani is the Celtic equivalent of Latin Regina (‘Queen’). The ‘Queen Goddess’ is honoured in Worringen (Germany),791 Lanchester (GB),792 and Lemington (GB)793 (see Chapter 3). The offering would have thus been made to both Rigani and Rosmerta and the inscription would read:

‘I have offered this to the ‘Queen’ (and) to Rosmerta.794 ’On the other hand, Rigani and Rosmerta may be two epithets designating the same deity. This is the more likely interpretation, for Regina is a title which is sometimes given in the epigraphy to the Roman goddesses Juno, Minerva and Fortuna and to the Gallo-Roman horse goddess Epona.795 The inscription would then read:

‘I have offered this to Rigani Rosmerta, i.e. the Queen Rosmerta.796 ’However, Lambert in the RIG II.2 suggests another possible interpretation, which he argues is the most probable one.797 According to him, the coordination between the words Rigani and Rosmerta is definitely not possible. Therefore, it cannot be an offering to two separate deities. He interprets the final word Rosmertiac as an abbreviated form of Rosmertiac[on], a word in –āko- designating a name of feast, that is ‘the feasts of Rosmerta’. Feasts held in honour of land-goddesses are known in Irish medieval literature, such as Óenach Macha (‘Macha’s Assembly’) for Macha and Óenach Tailten (‘Tailtiu Fair’) for Tailtiu, two earth-goddesses par excellence (see above). This theory is thus plausible. Lambert reckons that the word rigani could refer to a (human) queen, who would have made the offering. From this, it follows that the inscription should be read:

‘This I offered, (me) the queen of the feasts of Rosmerta.798 ’

Finally, the name of the goddess may appear on a fragment of vase in marble, found in Austria (Noricum*) between 1980 and 1990 in an unidentified field: [----Ros]mertai [----].799This object has been interpreted as an offering to the Goddess.