B) Atesmerta

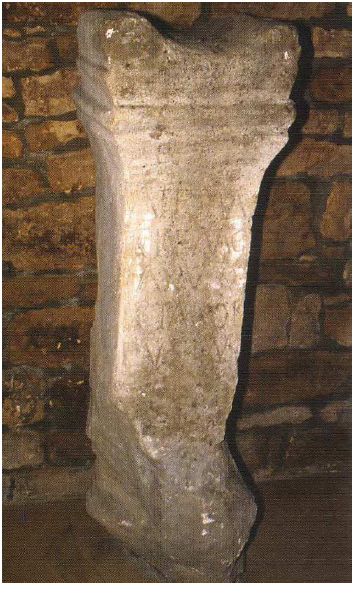

The goddess Atesmerta is known from a single inscription, discovered in 1918, at a place known as ‘Combe-du-Champ-Bas’, located in the heart of the Forest of Corgebin, in the commune of Chaumont-Brottes (Haute-Marne), in the territory of the Lingones.816 The altar was found together with bones, fragments of pottery and coins from the mid-3rd c. AD: Atesmert(a)e Magiaxu(s) Oxtaeoi f(ilius) v.s.l.m., ‘To Atesmerta, Magiaxus, son of Oxtaeus/Oxtaius paid his vow willingly and deservedly’ (fig. 20).817 The goddess name Atesmerta is composed of the intensive prefix ate-, ad-, ‘very’ and of the root smerto-, ‘distribution’.818 Atesmerta is therefore equivalent in meaning to the goddess name Rosmerta and can also be glossed as ‘Great Purveyor’. The names of the dedicators Magiaxus, based on magi, ‘great’, ‘big’,819 and of his father Oxtaeus or Oxtaius,820 are Gaulish. This attests of the indigenous character of her cult. Her name is seemingly the feminine version of the god names Atesmertius (Apollo) venerated in Le Mans (Sarthe),821 Atesmerius honoured in Meaux (Seine-et-Marne)822 and Adsmerius mentioned in Poitiers (Vienne).823

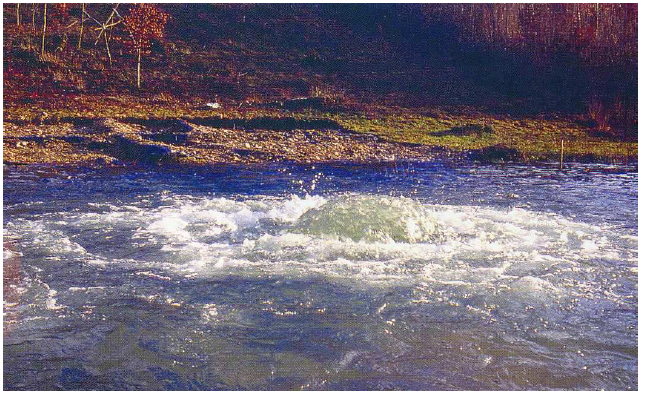

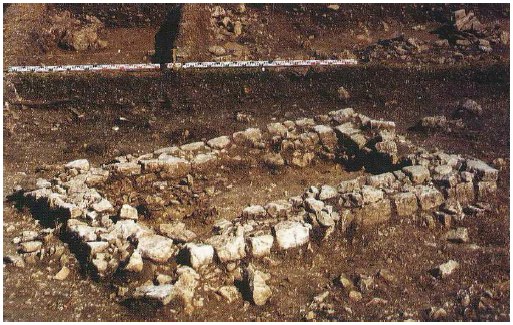

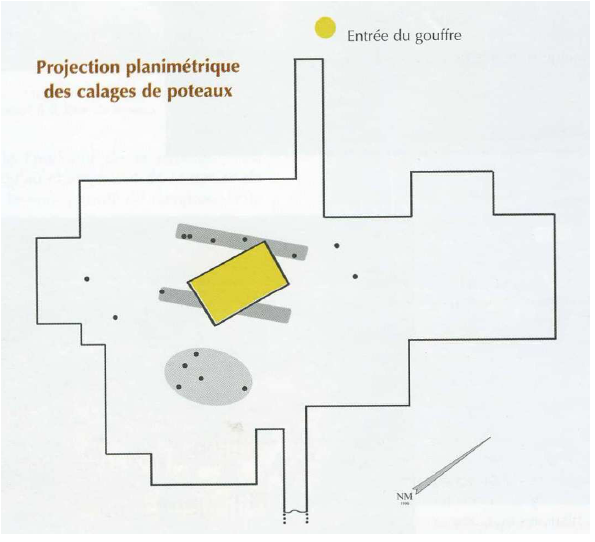

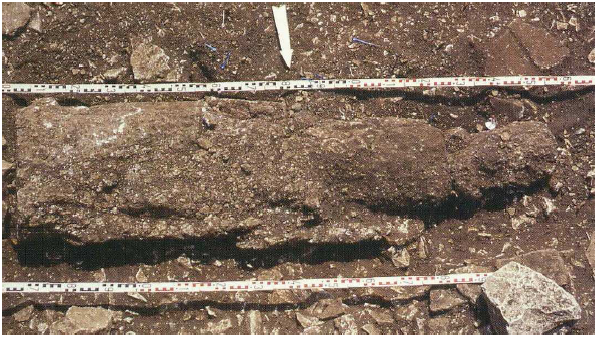

Excavations carried out unofficially by Luc Thomas between 1989 and 1992 revealed a 15-metre deep chasm, called the ‘Gouffre des Bonshommes’, and a subterranean river, where a bowl in ash wood and 300 Roman coins and a few Gaulish coins were found.824When the water-level rises, the river gushes from the chasm and provokes a sort of geyser, rising sometimes up to 1.50m and flooding the valley over several kilometres (fig. 21). Nearby, a small rectangular temple, called cella*, probably built over a primitive place of worship in wood, evidenced by the alignment of five pole holes of previous date, was unearthed (fig. 22 and 23).825 In the area of the temple was discovered a much damaged 1.55m high statue of a woman, which may be the representation of the goddess Atesmerta (fig. 24). Various anatomical ex-votos*, such as a webbed hand, a leg, heads and busts, similar to those from the Sources-de-la-Seine, were also found (fig. 25).826 Thomas explains that other alignments of pole holes discovered on the site could be indicative of a place where the ex-votos were deposited.827 A study of the coins revealed that the sanctuary was in use from c. 50 BC to the second half of the 3rd c. AD, when it was then destroyed. It seems clear that the sanctuary was erected in connection with the ‘geyser’, the appearance of which was limited in time and unidentifiable, and thus mysterious and sacred. It must have been understood as a divine manifestation or a benediction from the gods. The altar dedicated to Atesmerta clearly proves that she was the goddess presiding over the place and the anatomical ex-votos* suggest that people came to pray her so as to have their pains soothed. From this, it can be affirmed that Atesmerta was a local healing spring-goddess.