2) Iconography with inscriptions

One clear portrayal of the couple accompanied by a dedication naming them is the altar discovered in Eisenberg, located near Göllheim and Grunstadt (Germany) (fig. 30).888 The inscription engraved under the figuration is the following: Deo Mercu(rio) et Rosmer(tae) Marcus Adiutorius Memmor d(ecurio) c(ivitatis) st(…) ex voto [v(otum)] s(olvit) l(ibens) m(erito), ‘To the god Mercurius and to Rosmerta, Marcus Adiutorius Memmor, decurio civitatis, st(...)? offered this and paid his vow willingly and deservedly’. The dedicator bears Latin names and the tria nomina of Roman citizens. He is a member of the ruling class, since he is a decurio civitatis*, that is a member of a city senate who was in charge of public contracts, religious rituals, order, local tax collection, etc.

The Roman god Mercurius, counterpart of the Greek god Hermes, is easily recognizable on this relief*. Naked and beardless, he bears the attributes which are characteristic of him, such as the petasus* or winged hat and the caduceus*, a herald’s staff crowned with two snakes, standing for his role as messenger of the gods. The purse he holds in his right hand symbolises his functions as protector of commerce, merchants and travellers - his role being illustrated by his name derived from Latin merx, ‘merchandise’ and mercari, ‘to trade’, ‘to traffic’.889 As for the goddess standing beside him, she wears a tunic and a coat, and holds a patera* in her right hand and a purse in her left hand. This typifies her role of land-goddess and echoes the functions of her consort. Another anepigraphic stele* of the same type was discovered in Eisenberg.890 The god bears the exact same attributes and the goddess probably holds a patera* with her two hands. A goat, which is, with the cock and the tortoise, the emblematic animal of Mercurius, is placed between the two divinities. In view of the other portrayal with inscription, it can be inferred that this altar is a representation of Mercurius and Rosmerta.

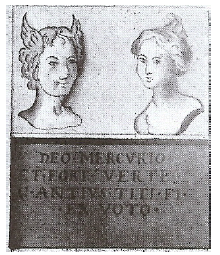

The second epigraphic stele* was discovered in 1615 in Langres, in the territory of the Lingones.891It is now lost and only a somewhat doubtful drawing, made by Montfaucon, remains. It represents the busts of a god with petasus* and a goddess wearing a coat on her shoulders, under which the following inscription is engraved: Deo Mercurio et Rosmerte Cantius Titi filius ex voto, ‘To the god Mercurius and Rosmerta, Cantius son of Titi according ot his vow’ (fig. 31). According to Dondin-Payre, the name of the dedicator Cantius is an indigenous Latin unique name, while the name of his father Titi is Celtic.892Cantius and Titi are peregrines.

As one can notice, the two epigraphic reliefs* from Eisenberg and Langres do not shed light on the nature and functions of Rosmerta, who appears as a mere goddess of prosperity beside the god Mercurius.