2) A Celtic Deer Goddess?

Flidais, in Modern Irish Fliodhais, is usually understood as a woodland deer-goddess, presiding over the wild animals, forests and hunting, which is why she is generally compared to the Greek Artemis and Roman Diana. The analysis of the various texts mentioning her will however demonstrate that these ideas are inaccurate and give a misleading image of the goddess.

First of all,Flidais is remembered in Irish medieval literature for her cattle called buar Flidais (‘cattle of Flidais’), mentioned for instance in the Lebor Gabála Érenn [‘The Book of Invasions’], in which she is said to be one of the Tuatha Dé Danan and the mother of four daughters:

‘Flidais, diatá buar Flidais; a cethri ingena, Airgoen 7 Bé Chuille 7 Dinand 7 Bé Theite.Flidais, of whom is the ‘Cattle of Flidais’ ; her four daughters were Argoen and Be Chuille and Dinand and Be Theite.979 ’

In T á in B ό Flidais [‘The Cattle Raid of Flidais’], the earliest versions of which date from the 9th and 10th c., she is made the wife of Fergus Mac Rόich and is similarly associated with cattle and cows. Here is an extract of the earliest version (9th c.) contained in the Book of Lecan:

‘Et doberat Flidais assin dún, 7 dobreth a m-bái di chethrai and .i. cét lulgach 7 secht fichit dam, 7 tricha cét di chethrai olchena.And they took Flidais out of the fortress and they took all the cattle that were there and a hundred calved cows and seven twenties calving cows and thirty hundred of cattle in general. It was after that that Flidais went to Fergus Mac Róich.980 ’

As for the translation by Olmsted of the 10th-century version of T á in B ό Flidais, comprised in the Book of the Dun Cow, it is inaccurate and misleading.981 Flidais is indeed not identified with cows and does, as he maintains, but with cows and bullocks (damaib):

‘7 toberat Flidais leo assin dun […] 7 oberat a m-bái di cethrib and .i. cet lulgach, 7 da fichit arc et do damaib, 7 tricho cet di mincethri olchenae […] Ba sé sin búar Flidais.982And they took Flidais out of the fortress […] And they took all of the cattle that were there, that is a hundred calved cows and a hundred and forty of bullocks and thirty hundred of small cattle in general […] That was the cattle of Flidais.983 ’

Flidais is once again paired with cows in a text entitled Benn Boguine [‘The Peak of Bogun’],984 dated 9th c., mentioned in the Metrical Dindshenchas:

‘Fecht dia tánic sunda, mar cach ngábit ngalla, ón mnaí cen lúaig lumma bó da búaib dar Banna.Flidais ainm na mná-sin ingen Gairb maic Grésaig ind fairenda fial-sin, ben Ailella fésaig.

Co rothόed in bó-sin dá lόeg ar in lúth-sin, gnό garb, nárbu gnáth-sin, bό ocus tarb don túr-sin.

Hither came, once on a time, as it were any foreign [...] straying from a woman, a beast of price, one of her cows, across the river Bann.

Flidais was the name of that woman, daughter of Garbh son of Gréssach; that well-accompanied generous one, wife of bearded Ailill.

That cow dropped two calves on that run; a rough business, which was not unusual, a cow and a bull on that journey.985 ’

Thurneysen believes that Flidais is the archetype of the woodland-goddess, guardian of the forests and wild animals, comparable to Diana or Artemis.986 To support this idea, he proposes to relate the name Flidais to the word os signifying ‘faun’. This theory would imply that Flidais is written in two words, that is Flid Ois, ‘wetness of faun’, with the significance of ‘untamed’. This would give a genitive buar Flid Ois. It is however noticeable that this form never appears in the texts. In addition to always being written as one word, Flidais is never spelt with the letter ‘o’. Therefore, it is clear that Flidais cannot be connected to the word os, ‘faun’ and be envisaged as a woodland-goddess. Besides, Ó hÓgáin points out that the antiquity and genuineness of Flidais is problematic, for her name is never declined in the texts, whereas all the other divine names are.987 Indeed, Flidais should be Flidaise in the genitive, and buar Flidais (‘Cattle of Flidais’) should be written buar Flidaise, but these forms are never encountered in the texts. This must be indicative of a medieval invention. In view of this, it must be acknowledged that Flidais is highly likely not to be a genuine goddess. To support that idea, it is necessary to study her relation to Niad Ségamain, to which her association with cows and does is actually due.

In the c. 9th-century Corpus Genealogiarum Hiberniae [‘Corpus of the Geneaologies of Ireland’], a corpus containing all the important Irish pedigrees and genealogical material from the earliest literary period down to c. 1,500 AD, Flidais is said to be the mother of Niad Ségamain and they are both associated with milking, cows and does:

‘Niad-Segamain lasa mbligtis diabulbuar .i. baī 7 elti. Flidais Foltchaīn a māthair diambtar bāe eltiNiad-Segamain, by whom were milked double cattle, that is cows and does. Flidais ‘the Fine-haired’, his mother, to whom does were cows.988 ’

If the name Flidais seems not to be genuine, Niad Ségamain undoubtedly is. The antiquity of his name is certain, for the first element Niad, known in Old Irish as nía, genitive niath, ‘warrior’, is derived from a Celtic form *netos meaning ‘leader’ or ‘warrior’, attested as a divine name in inscriptions from Spain (Lusitania): Neto in Conimbriga and Netoni in Trujillo.989 Similarly, the second element of his name Segamain is similar to the god name Segomo(ni), known from various dedications found in Gaul.990 Segamain and Segomoni are both based on the Celtic root sego- meaning ‘force’, ‘vigor’, ‘victory’.991 Finally, the name of Niad Ségamain appears in two Ogam scripts, dated 5th or 6th c. AD, discovered in Waterford: Neta Segamonas and Netta Segomonas.992

The fanciful etymology* proposed for the name Nia Ségamain in the c. 13th-century Cóir Anmann [‘The Fitness of Names’] is obviously due to the inability of the medieval writers to understand its significance. This misled them to relate Ségamain to words, such as seg ‘milk’, segamail, ‘milk-producing’ or ségnat, ‘little deer’, extrapolating from this that Nia Ségamain was connected to the milking of cows and does, which is pure medieval speculation.993 The text explains that his father is Adammair and his mother Flidais:

‘Niadh Séghamain .i. is ségh a maín, ar is cuma nόblighthea bai 7 eillti fon aenchumai cach día ré linn, ar bá mόr in main dό na neiche sin sech na righu aili. Ocús is sí in Flidhais sín máthair Níadh Ségamain maic Adamair, 7 do bhlightheá a flaith Niadh Ségamain in búar sin .i. diabulbhúar .i. bá 7 eillti do bhliaghan re linn Níadh Ségamain, 7 issí a máthair tuc in cumhachta tsidhamail sin dó.Nia Ségamain, that is, ség ‘deer’ is a máin ‘his treasure’ ; for during his time cows and does were milked in the same way every day, so to him beyond the other monarchs great was the treasure of these things. And it is that Flidais (above-named) who was the mother of Nia Ségamain son of Adammair ; and in Nia Ségamain’s reign those cattle were milked, that is, double cattle, cows and does, were milked in the time of Nia Ségamain, and it was his mother that gave him that fairy power.994 ’

And in the Lebor Gabála Érenn [‘The Book of Invasions’], it is worth noting that his father is called:

‘Adamair Flidais de Mumain .i. mac Fhir Chorb.Adamair Flidais of Mumu, son of Fer Corb.995 ’

This tends to indicate that Flidais was originally an epithet for Adamair and must have been misunderstood by some glossators as a separate name designating the wife of Adamair. From this was invented the supernatural female figure Flidais to whom were given the same fanciful functions of milking and protecting cattle, cows and does as her son Niad ; those attributes actually ensuing from the medieval speculations over the significance of Niad Ségamain’s name.

From this, it follows that Flidais is a pure invention of medieval writers and therefore not a goddess in origin. Moreover, she is not a deer-goddess, protecting and reigning over the wild animals and the forest, as it is often claimed by scholars,996 but presides over domestic animals, for medieval literature associates her with cattle and cows. She is sometimes related to does because of her filiation to Niad Ségamain, but as pointed out, this relation in only due to an etymological speculation in the medieval period. Her association with does might also have been encouraged by an equation with Greek Artemis, who is usually accompanied by a doe in the iconography.997 As for the belief, advanced by Marie-Louise Sjoestedt, in Celtic Gods and Heroes - which has unfortunately been repeated in many works - that Flidais is a woodland deity reigning over the beasts of the forests and travelling in a chariot drawn by deers, there is no textual evidence for such an idea.998 This assumption by modern scholars must come from the discovery of votive models of carriages, pulled by stags, oxen or swans, sometimes with a divinity standing in the middle, such as the bronze model cult wagon, dated 7th c. BC, from Strettweg (Austria). In the centre, a female deity supports a massive vessel with her head and two hands and is surrounded by deer, horses and soldiers (fig. 37).999 The theory of Flidais driving a cart led by deer may have also sprung from a fanciful assimilation with Diana, who is sometimes represented on coins driving a chariot drawn by does (fig. 38).1000

As regards Gaulish mythology, the deer cult seems to be represented mainly by gods, the most significant example being Cernnunos, whose name is generally accepted as meaning ‘the Horned One’.1001Cernunnos is known from a single inscription engraved on one of the four sides of the Nautes Parisiacae monument, dated c. 14-37 AD, discovered under the choir of the Cathedral Notre Dame de Paris, in Paris.1002 The name Cernunnos is engraved above the representation of a bearded god wearing two antlers, from each of which a torque* hangs (fig. 39).1003 This representation is very similar to the god figured on one of the plaques of the Gundestrup Cauldron (fig. 40).1004 The god is seated cross-legged and has long antlers coming out of his skull. He wears a torque* around his neck and holds another one in his right hand. In his left hand is a ram-headed snake, which is a typical Celtic mythological animal. The god is surrounded by various animals: a huge stag with long antlers stands on his right-hand side. On account of those two representations, it seems that the antlers, the torque* and the cross-legged sitting position are the attributes particularizing Cernunnos. It is nonetheless difficult to assert with certainty that all the portrayals of antlered gods, such as the relief* from Reims, the statuette from Autun or the relief* from Vendoeuvres (fig. 41) are figurations of Cernunnos.1005 The cult of a god in the shape of a stag may be reflected in Irish tradition in the supernatural figure of Derg Corra, a weird servant of Fionn mac Cumhaill, dismissed after one of Fionn’s lovers had fallen for him. Fionn went to search for him one day in the forest and saw him in a tree partaking a meal with a stag, a blackbird and a trout. This legend, dating from the 8th century, entitled The Man in the Tree, relates that Derg Corra went about the forest “on shanks of deer”, which is redolent of his shape-shifting power.1006 It is also worth noting that his name means ‘the Red Peaked One’. This, according to Ó hÓgáin, relates him to Cernunnos (‘the Horned or Peaked One’).1007 Other names in the Fianna lore may be evocative of such a cult. When he was young, the hero Fionn mac Cumhaill was called Demne, which is seemingly a corruption of damne, ‘little stag’.1008 Furthermore, the name of his son Oisín, earlier Oiséne, is a diminutive of the word os, ‘fawn’: Oisín is therefore the ‘Little Fawn’.1009 Finally, the name of the grand-son of Fionn mac Cumhaill, Oscar, may signify something like ‘deer-love’.1010 It is clear that deer cults and names particularly survived in the Fianna lore because of Fionn’s passion for deer-hunting.1011

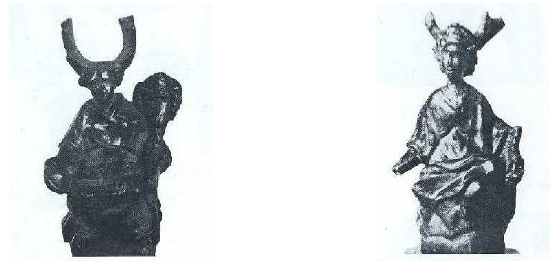

Representations of female deities with deer antlers are almost non-existent. There are only two instances, the place of discovery of which is imprecise and uncertain. The first example come from the Puy-de-Dôme and is now in the Musée de Clermont-Ferrand (fig. 42),1012 while the other example was found in Besançon (Doubs) and was then believed to be lost, but it is actually the statuette housed in the British Museum (fig. 42).1013 Those antlered goddesses are portrayed seated cross-legged, holding a patera* and a sort of bowl in their hands. Two other horned or antlered goddesses may be depicted on a fragment of pottery from Richborough (Kent), showing the bust of a goddess, and on the stone from Ribchester (Lancashire), but those instances remain questionable.1014 Wearing antlers and sitting cross-legged, those atypical goddesses could be viewed as the female equivalent and consort of Cernunnos. This might indeed be the case, for female partners can bear the attributes of their consort. As we noted above, the goddess accompanying Mercurius on some reliefs* from the east of Gaul sometimes has a purse and caduceus*.1015 However, Stéphanie Boucher points out that while the cross-legged antlered god is sometimes associated with a goddess in the imagery, the latter is never pictured crouching or antlered.1016 The goddess is a mere Mother Goddess bearing attributes of fertility.1017 Consequently, the two antlered goddesses from Clermont-Ferrand and Besançon cannot be envisaged as consorts ofCernunnos.

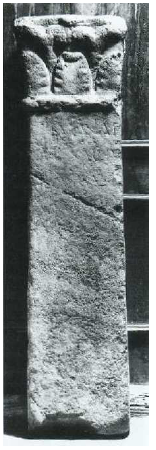

Their nature and functions are thus somewhat puzzling. They are undoubtedly not fountain- or river-goddesses as Camille Jullian suggests.1018 In Roman mythology, rivers are indeed personified by powerful bearded gods with two horns on their forefront or in the shape of bulls, such as the river god Achelous.1019 In Mosella, Ausonius also specifies that the river Mosel is horned.1020 Being female deities, definitely not wearing horns but antlers, those two goddesses cannot be viewed as personifications of rivers. According to Boucher, the cross-legged position and the antlers can be interpreted as “supplementary powers” magnifying the nature of the Mother Goddess,1021 but it must rather be the survival of some ancient belief in deities in deer-shape. In support of that idea comes an inscription engraved on a column discovered at Dobrteša vas, near Šempeter, in the territory of Celeia (Croatia), dedicated to the goddess Carvonia, whose name literally means ‘Doe’. It is based on the Celtic word carvo signifying ‘stag’, ‘deer’, cognate with Irish carr, Welsh carw, Old Cornish caruu, Breton karo.1022 The significance of her name implies that the goddess was worshipped in the shape of a deer, just as Artio (‘Bear’) must have been in bear shape or Damona (‘Cow’) and Bóinn (‘Cow White Goddess’) in bovine shape. The inscription reads: [Ca]rvoniae Aug(ustae) sacr(um) p[r]o salute C[n.] Atili Iuliani, ‘Sacred to the August Carvonia for the safety of C[n.?] Atilius Iulianus’ (fig. 43).1023 The fact that the dedication was made for the safety of Cn. Atilius Iulianus, who bears the tria nomina of Roman citizens, tends to indicate that Carvonia was a protective and salutary goddess. Šašel Kos compares her to Artemis/Diana and makes a woodland hunting goddess of her.1024 This dedication to a deer-goddess serves to illustrate the representations from Clermont-Ferrand and Besançon, where the goddesses have only kept the distinctive elements of the deer, that is the antlers.

Moreover, the concept of a deer-shaped goddess is well represented by several legends of Irish medieval literature which relate that certain female characters have the ability to transform into a doe. An 11th-century legend belonging to the tradition of Fionn mac Cumhaill tells that Blái Dheirg,1025 the mother of Oisín, generally appeared in the shape of a doe and gave birth to Oisínin this form, justifying thus his name ‘Little Fawn’:

‘Ticed i rricht eiltehi comdáil na díbergge.

co ndernad Ossine de

ri Blai nDeirgg i rricht eilte.1026

Blái used to come in the shape of a doe

And join the díbherg-band

So that Oisín was thus begotten

Of Blái Derg in the shape of a doe.1027 ’

The legend survived in 18th- and 19th-century popular oral versions of both Ireland and Scotland with some folk variants. They relate that Fionn’s wife was turned into a doe after being enchanted by a nasty personage and that she gave birth to Oisín while hunted by Fionn.1028 The pattern of the supernatural lady transformed into a deer appears in another 12th-century text of the Fianna cycle, Accallamh na Senórach [‘The Colloquy of the Old Man’], in which Caoilte mac Rónáin, a loyal friend of Fionn mac Cumhaill,1029 is told by the underworld lord (‘The Dark One’)1030 on a visit to the otherworld ráth (fortified place) that he sent the lady Máil to him in the form of a deer so as to allure him to his place. The meaning of that legend is that Donn had attracted Caoilte and a Fianna troop to visit him by using the ‘deer’ as a decoy, while the Fianna were hunting. They conversed with Donn and the Tuatha Dé Danann, feasted with them, and spent the night in the ráth:

‘[…] 7 ro chuirsemar in ingin Máil út ar do chennsa co Toraig thuaiscirt Eirenn, ar-richt baethláig allaid, 7 ro lensabairsi hé co rangabair in síd sa, 7 in maccaem út atchithi 7 in brat uaine aendatha uimpi ac in dáil, issí sin hí’, ar Donn.[…] and we sent that maiden Máil to meet you [i.e. Caoilte] to Tory (Island) in the north of Ireland, in the shape of a young wild deer-calf, and ye followed her until ye reached this dwelling, and the young one that ye see with the fully green mantel on her, that is her’, said Donn.1031 ’

This aspect is also mirrored in a 12th-century poem, entitled Faffand, comprised in the Metrical Dindshenchas, which recounts how the supernatural woman Aige was changed into a wild doe by the evil spirits:

‘Broccaid brogmar co n-gním gíall do chiniud gorm-glan Galían, dó ba mac Faifne in file, ní gó taithme tiug-mire.Ba hí máthair in maic maiss Libir ind láthair lond-braiss; ingen dóib in dían dírmach ind Aige fhíal il-gnímach.

Oll-mass in cethrur cáem cass; ba clethchur sáer co sognass; athair is máthair co n-áib, ingen is bráthair bláth-cháin.

Tucsat na siabra side– nír gním tiamda téithmire– delbsat i n-deilb láig allaid Aigi sáir co serc-ballaib.

Roshír h-Érinn or i n-or re cach n-albín rúad rogor, corchúardaig Banba m-brethaig co calma fo chaém-chethair.

Tarnic a gním is a gal, fríth sund co sír a sernad; tucsat i m-brianna i m-bine fianna Meilgi Imlige.

Broccaid the powerful with winning of hostages, of the bright and famous race of the Galian, he had a son, Faifne the poet; the record of his final madness is no falsehood.

It was she was the mother of the comely son,– even Libir quick and eager of mood: their daughter was the swift lady of the hosts Aige, the noble and skilful.

Exceeding fair were the four, curled and gentle; they were a noble kin, of virtuous behaviour, the father and the lovely mother, the daughter and the brother soft and fair.

The evil spirits made an onset (it was no feeble deed of wanton folly):–they changed into the form of a wild doe the noble Aige of the love-spots.

She traversed Erin from shore to shore fleeing before all the fierce and fiery packs; so that she coursed round Banba, land of judges, bravely, four fair times.

Her doings and her valiance had an end, here came to pass her final dissolution; they tore her in pieces in their wickedness, did the warriors of Meilge of Imlech.1032

The two Gaulish statues of antlered goddesses from Clermont-Ferrand and Besançon, the inscription from Dobrteša (Croatia) dedicated to the goddess Carvonia, whose name literally means ‘Doe’, and the 11th- or 12th-century Irish legends telling of deer-shape-shifting goddesses are suggestive of a belief in the existence of a Deer Goddess in Celtic times. Flidais, however, cannot be understood as an indication of such a cult, for, as demonstrated, she is not a genuine goddess and is clearly not related to does but to cattle. Her presumable association with deer is actually due to fanciful and inaccurate medieval and modern interpretations.’