5) The Duilliae and the Vroicae

Significant goddesses of the plant kingdom may be the Duilliae, who are venerated in two dedications from Palencia (Vieille-Castille), in the Iberian Peninsula:1077 Annius Atreus Caerri Africani F(ilius) Duillis V(otum) S(olvit) L(ibens) M(erito), ‘Annius Atreus Caerrus son of Africanus to the Duillae paid his vow willingly and deservedly’,1078 and Cl(audius) Latturus Duillis v(otum) s(olvit) l(ibens) m(erito) [e]x vi(su), ‘Claudius Latturus to the Duillae paid his vow willingly and deservedly after having a vision’.1079 The two dedicators are Roman citizens, since they bear the tria and duo nomina. The goddess name derives from a Gaulish root dulio-, dulli- meaning ‘leaf’, cognate with Irish duille, duillén, ‘leaf’.1080 The Duilliae may therefore be glossed as the ‘Leaves’ or the ‘Leafy’. They may be related to the god Dulovius, worshipped both in Gaul and Celtic Hispania. He is indeed honoured in two lost inscriptions discovered in Vaison-la-Romaine (Vaucluse). The first one, probably found at the beginning of the 17th c., read: Dullovio M(arcus) Licinius Goas v.s.l.m., ‘To Dullovius Marcus Lucinius Goas paid his vow willingly and deservedly’.1081 The second inscription: Dulovio, ‘To Dullovius’ was engraved on an altar, which had the engraving of a god surrounded by palm leaves on the other side.1082 In the Iberian Peninsula, he is venerated in Cáceres (Estramadure): M(arcus) F(abius) […] Scelsus Aram Qua(m) Donavit [P]os(uit) Anim(o),1083 and in Villaviciosa (Grases), where he is given the epithet Tabaliaenus: [Dul]ovio Tabaliaeno Luggoni Arganticaeni haec mon(umenta) possierunt.1084 Like the Dulliae’s name, Dulovius’ name signifies ‘the Leafy’ or ‘the One of the Leaves’; an aspect illustrated by the palms leaves surrounding the god in the relief* from Vaison.1085

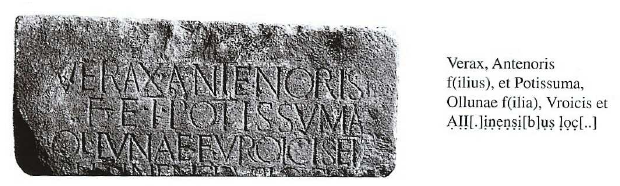

Even though the nature and etymology* of the Vroicae remain unsure, they are worth mentioning here. They are honoured along with the Aldemehenses (?) in a dedication from Rogues (Bouches-du-Rhônes). Their name literally means ‘heather’ in Celtic – an old form *vroica survived into the Old Irish froích, fróech, ‘heather’.1086 The inscription was found in the park of the Château de Beaulieu in 1887, 3.5 kms to the south-east of Rognes: Verax Antenoris f(ilius) et Potissuma, Ollunae f(ilia), Vroicis et AII[.]inensi[b]us loc[..], ‘Verax, son of Antenor, and Potissuma, daughter of Olluna, to the Vroicae and to the A[…]inenses […]’ (fig. 46).1087 As their unique name indicates, the two dedicators are peregrines, who bear Celtic names: Antenor and Potissuma.1088 Potissuma’s mother, Olluna, has a Celtic name and Antenor’s father, Verax, has a Germanic name according to Dondin-Payre.1089 Being known by this single inscription, those deities remain difficult to apprehend. Their gender was even questioned, but today they are commonly accepted as female deities.1090 Allmer suggests the Vroicae and the Aldemehenses are rural deities, while Yves Burnand maintains they are protective deities of the place.1091 As for Paul Aebischer, he has argued that the Vroicae were water-goddesses, whose cult survived in some hydronyms* of Switzerland.1092 They could be etymologically related to the god Vorocios, whose name is evidenced on a bronze ring found in a well in Vichy (Allier) and survived in the antique name of Vouroux, Vorocium, situated 20 kms from Vichy.1093 His name might indeed be a deformation of Vroici, Vroicae, ‘heather’, but its composition does not seem to support that idea.1094