6) The Black Forest: Abnoba (Diana)

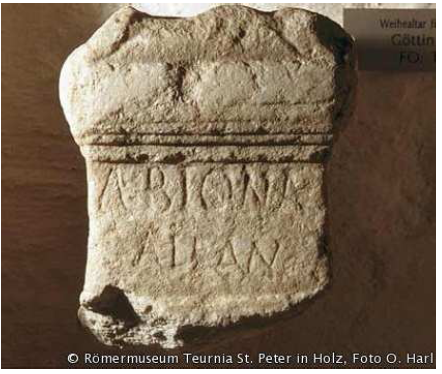

The name, functions and attributes of the goddess Abnoba, known from nine inscriptions discovered in the area of the Black Forest in Germany, remain somewhat obscure. It is significant that both Pliny and Tacitus gave her name to the mountain of the Black forest: Montis Abnovae or Abnobae.1095 It tends to prove that Abnoba was the personification of this peak, like the god Vosegus was the embodiment of the Vosges Mountains. The meaning of her name is indefinite. Alfred Holder proposes to relate it to theCeltic word abona signifying ‘river’, cognate with Old Irish aba, abainn (standard spelling abha, abhainn), Welsh afon, Breton aven, ‘river’, all coming from an IE root *ab- designating ‘the waters’ as supernatural beings.1096 Several rivers in Britain, such as the various rivers Avon and the Scottish River Awe, are derived from Abona.1097 Two other goddess names from Portugal and Austria are based on the same root ab-, ‘divine water’. The goddess Abna is known from a single inscription discovered in Santo Trison (Douro Littoral, Portugal)1098 and the goddess Abiona is honoured in Sankt Peter in Holz, Austria: Abionae Albanus […], ‘To Abiona, Albanus […]’ (fig. 47).1099 The dedicator Albanus has a Celtic name, derived from the root alb-, ‘celestial’.1100

Abnoba is venerated on her own in dedications from Cannstatt: Abnobae sacrum M. Proclinius Verus Stator v. s. l. l. m ; [a]bn[obae] [s]a[crum],1101 from Pforzheim: In h(onorem) [d. d.] Abn[obae et] Quad[rubis] ; [Ab]nob(a)e […] Iulius […],1102 from Waldmössigen: Abnobae Sacrum L Vennon[i]us Me[…],1103 and from Rötenberg: Abnobae Q. Antonius Silo leg(ionis) I aduitricis et leg(ionis) II adiutricis et leg(ionis) III Aug(ustae) et leg(ionis) IIII F(laviae) f(elicis) et leg(ionis) XI C(laudiae) p(iae) f(idelis) et leg(ionis XXII p(iae) f(i)d(elis) v.s.l.l.m (dated 89-96 AD).1104

Abnoba is equated with the Roman woodland-goddess Diana in two dedications. The one from Mühlenbach reads: In h(onorem) d(omus) d(ivinae) Deanae Abnobae Cassianus Casati v(otum) s(olvit) l(ibens) l(aetus) m(erito) et Attianus frater Falcon(e) et Claro co(n)s(ulibus).1105 The dedicator bears the duo nomina; he is thus a Roman citizen. His gentilice* Cassianus is a Latinized name of Celtic origin and his cognomen* Casatus is Celtic.1106 The votive formulas In h. d. d. and dea indicate that the inscription dates from the first half of the 3rd c. AD.1107 The second inscription was discovered in the ruins of a Gallo-Roman thermal establishment, in Badenweiler. Dianae Abnob[ae], ‘To Diana Abnoba’ was engraved on the socle of a statue which had disappeared.1108 Excavations carried out by Werner Heinz and Rainer Wiegels around 1980 at Badenweiler revealed other fragments from this altar. The archaeologists were then able to reconstruct the complete dedication: Dianae Abnob[ae] M(arcus) Senn[i]us [F]ronto s[---] ex voto, ‘To Diana Abnoba, Marcus Sennius Fronto offered (this altar)’.1109 The dedicator bears the tria nomina of Roman citizens. While his praenomen* Marcus and cognomen* Fronto are Latin,1110 his nomen* is Celtic: Sennius (‘Old’).1111 This proves that the Celtic origin of the dedicator and his attachment to his roots and cults. Jacqueline Carabia argues that Abnoba was given curative water functions specifically in Badenweiler, like Diana Tifatina had a famous healing water sanctuary in Capoue.1112

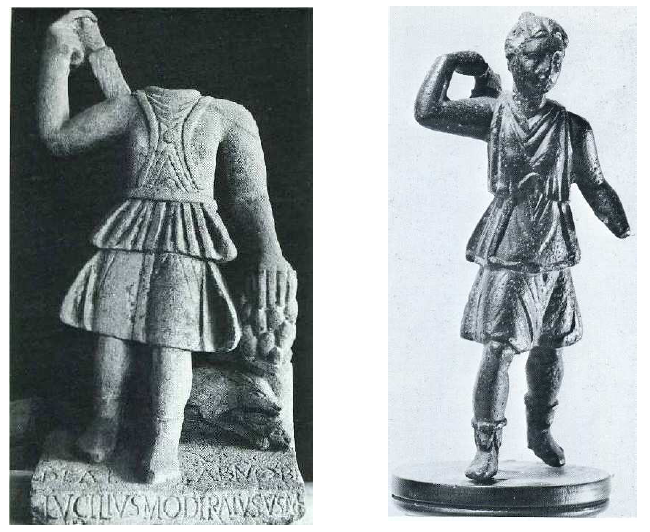

In Mühlburg, near Carlsruhe, the dedication Deae Abnob(a)e Lucius Moderatus v.s.(l.) m., ‘To the Goddess Abnoba Lucius Moderatus paid his vow willingly and deservedly’, is engraved on the socle of a statue, the head of which is missing, found in 1850 (fig. 48).1113 The dedicator Lucius Moderatus is a Roman citizen. He bears the duo nomina, a form particularly in use at the end of the 2nd c. AD.1114 The goddess is represented in the features of Diana, but the style is crude and of indigenous character.1115 The proportions are not respected and the goddess does not have the acknowledged grace of Diana. Carabia adds that “the male features of the goddess evoke the stocky Gaulish women who participated in the fighting”.1116 The subject is nevertheless very similar to the statue in bronze of Artemis/Diana housed in the Musée des Beaux-Arts de Lyons (fig. 48).1117 In the Carlsruhe statue, Abnoba wears a short tunic (chiton*) and small boots. She leans her left hand on a sort of mound of round fruit or a rock and plunges her right hand into a quiver tied up on her back. A dog holding a hare in its paws lies at her feet.

As her name might mean ‘divine waters’ and is given to the mountain of the Black Forest and as she is equated with Diana in two inscriptions and a portrayal, it can be assumed that Abnoba was the embodiment and protectress of the mountain, the Black Forest and its rivers, perhaps even the Danube which rises in the forest.