2) Bergusia / Bergonia (‘the Hill’)

The goddess name Bergonia is known from a single inscription discovered in 1847 in the area of Viens, a commune located on the Monts de Vaucluse, a massif of the South PreAlps, between Apt and Céreste (Vaucluse), in the territory of the Albiques, where important oppida* have been unearthed. The inscription is the following: Bergoni(a)e G(aius) L(---) Calvo v(otum) s(olvit) l(ibens) m(erito), ‘To Bergonia Gaius L(---) Calvus paid his vow willingly and deservedly’ (fig. 52).1144 The dedicator is a Roman citizen, for he bears the tria nomina.

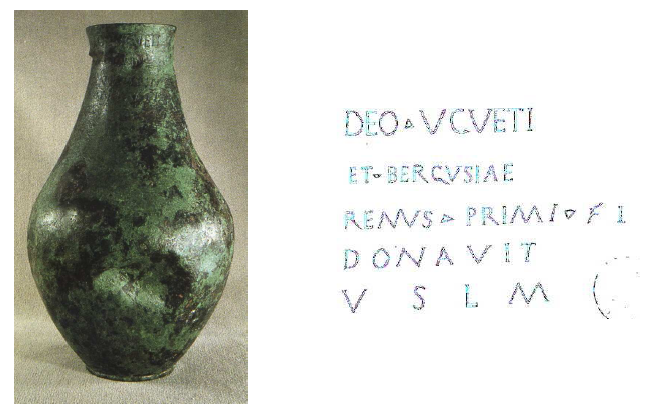

According to Guy Barruol, Bergonia is etymologically linked to the goddess Bergusia,1145 who is venerated with the god Ucuetis in a single inscription engraved on the neck of a bronze vase, discovered in the crypt of an antique monument dating from the 1st c. BC, excavated between 1908-1911 and 1961-1962 on Mont-Auxois, the hill overhanging Alise-Sainte-Reine (Côte d’Or), in the territory of the Mandubii.1146The dedication reads: Deo Uceti et Bergusiae Remus Primi fil(ius) donavit v.s.l.m., ‘To the god Ucetis and to Bergusia, Remus, son of Primus, offered (that vase) and paid his vow willingly and deservedly’ (fig. 53).1147 The dedicator is a peregrine*, since he has a unique name, but his name and his father’s name are Latin.

The god Ucuetis is venerated on his own in two other dedications from Burgundy. The first inscription was found in Entrains-sur-Nohains (Nièvre) and reads: In hono[rem domus divinae] deo Ucu[eti---], ‘In honour of the Divine House and to the God Ucuetis […]’.1148 The use of the abbreviated formula In h.d.d. indicates the inscription dates from the beginning of the 3rd c. AD.1149 The second dedication was discovered in 1839 on the same site as the bronze vase: Martilis Dannotali ieuru Ucuete sosin celicnon etic gobedbi dugiíontiío Ucuetin in Alisia, ‘Martialis, son of Dannotalos offered to Ucuetis this building (celicnon), and this with the smiths who honour Ucuetis in Alise’.1150 This dedication is of great interest, for it is in Gaulish language and Latin lettering and mentions the erection of a monument in homage to the god. This monument was excavated during the two campaigns of excavations in 1908 and 1960.1151 The edifice, probably dating from the 3rd c. AD, is composed of a 25mx13m rectangular yard, surrounded by a 4-metre portico, of various buildings and rooms, where many iron and bronze tools and debris were found,1152 and of an underground crypt, where the bronze vase dedicated to Ucuetis and Bergusiawas discovered (fig. 54 and 55).1153 The dedicators being smiths (gobedbi), these iron scraps were interpreted as votive offerings deposited in the sanctuary to honour the patrons of smiths and metal work. Roland Martin and Pierre Varène, who were in charge of the 1960 excavations, explain:

‘Unless the building is to be understood as a workshop or a shop, all these objects - which are grouped together in series (keys, locks, rings, adorned handles, hinges and split hinges, etc.) - cannot be considered to have had a merely practical purpose, since the two rooms do not have enough doors or enough furniture to explain this accumulation of objects. We would suggest that most of them were ex-votos or offerings deposited near an altar, in a room with a ritual use. They represent tokens of favour or recognition towards deities affording protection for smiths, and for bronze- and other metal-workers, whose skills were a source of considerable wealth and fame for the town of Alésia.1154 ’Lambert adds that this monument must have been a place of worship as well as a place where the guild of smiths could gather, meet and work.1155

Scholars do not agree on the significance of Ucuetis and diverse etymologies have been suggested. At the end of the 19th c. and the beginning of the 20th c., several etymologies, now dismissed, were put forward. A radical uc-, ‘elevation’ was first recognized andUcuetis was glossed as ‘the god of the summit’.1156 Then, John Rhys proposed to relate Ucuetis to a verbal theme ucu- meaning ‘act of choosing’, ‘choice’. Ucuetis was translated as ‘the Loving or Choosing One’.1157 Léon Berthoud, on the other hand, denied the Gaulish origin of this divine name,1158 Georges Poisson recognized in Ucuetis a Celtic root *cuet- signifying ‘to beat the metal’ or ‘to forge’, derived from an IE root (but which one?) meaning ‘to strike’ or ‘to beat’, which gave in Middle Irish cuad and in Latin cudo, ‘to beat’.1159 According to him, Ucuetis would thus be ‘the (Good) Striker’. This would illustrate his role of metal beater and relate him to the hammer-god Sucellus. As for the theory of Eugène van Tassel Graves that Ucuetis means ‘Swift Flyer’ and is a horse-god, it is fanciful and baseless, as Lambert points out.1160 The etymology* advanced by Olmsted is not convincing either. He considers Ucuetis a purely local god, whose name would be a toponym* meaning ‘Pine Saplings’.1161 As for Schmidt, he proposes ‘the One who is invoked’, relating his name to the verbal theme *uekw- / *ukw, ‘to speak’ or ‘to invoke’.1162 Finally, Lambert suggests to see a theme in *okuo-, ‘sharp’ or ‘pointed’ - cf. Latin accus - with an agent name in –ti-. Ucuetis would thus be ‘The Sharpener’; an etymology* perfectly suiting his function of patron of smith craft.1163 Lambert’s etymology* is the most cogent, but Schmidt’s cannot be ruled out.

Seven stone reliefs* representing a seated hammer-god and a goddess bearing the traditional symbols of abundance and fertility were discovered from 1803 to 1923 in Alise-Sainte-Reine.1164 It is generally agreed that those reliefs* are depictions of Ucuetis and Bergusia, but this is not possible to assert, for they all are anepigraphic. Moreover, those images do not differ from the various depictions of divine couples found throughout Gaul. It could be for instance the portrayal of the god Sucelluswith a Mother Goddess, notably when the god is represented with a hammer.

While Ucuetis is clearly a guardian of metalwork, Bergusia must have originally been a goddess attached to the Heights, Mounts or Mountains, for her name is based on a Celtic root berg(o), bergusia, literally signifying ‘mount’, from an IE root *bherĝh, ‘high’.1165 It is besides interesting to note that the root brig-, ‘high’, ‘eminent’, comprised in the divine names Brigantia, Brigit and Brigindona, comes from the same IE root.1166 They are thus goddesses of the same type and essence. The goddess name Bergonia and the epithet of the Germanic Matronae Berguiahenae, venerated in Gereonsweiler, Bonn and Tetz (see Chapter 1), are also derived from the root berg-.1167 Berg- is found again in the epithet of Damona Matuberginis, mentioned in a dedication from Saintes (Charente-Maritime). This attributive byname* can be either descriptive and mean ‘The High Favourable’, with matu-, ‘favourable, good’, or topographical and designate a local mount where the goddess would have been specifically venerated, possibly ‘the Hill of the Bear’(?), with matu-, ‘bear’ (see Chapter 4 for more details).1168

Bergonia and Bergusia are therefore to be understood as goddesses personifying and reigning over the mount. While Bergonia was certainly linked to the Monts de Vaucluse, situated near Viens, Bergusia was undoubtedly worshipped in Alise-Sainte-Reine in connection with Mount-Auxois. Poisson’s theory that Bergusia was more than a mere goddess of mounts, because she was coupled with a god of metal work, is somewhat unlikely but is worth reporting here.1169 Poisson argues that the root berg- must have by extension designated the mining riches of the mountains. From this, he assumes that Bergusia was ‘a Goddess of Mines’, protecting ores and completing the role of her metal-worker partner.