3) Goddesses in Brig- (‘the High One(s)’)

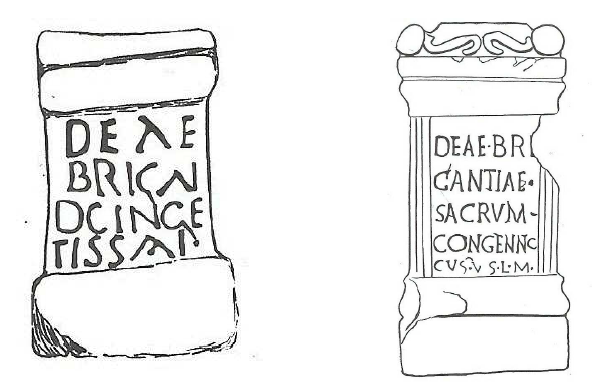

In Great Britain, seven inscriptions are dedicated to the goddess Brigantia. Three come from South West Yorkshire, while the four others come from about a hundred miles away, in the region of Hadrian’s Wall. Brigantia is obviously cognate with the name of the tribe of the Brigantes, who inhabited the region where the inscriptions were found (see Chapter 3). The inscription from Brampton (Hadrian’s Wall) describes her as a nymph,1170 while the dedications from Birrens, Greetland, Castleford and Corbridge equate her with Roman goddesses of war, such as (Minerva) Victory and (Juno) Caelestis.1171 The last two inscriptions are significant, for they are offered by dedicators of Celtic stock, although they come from Roman military camps or sites (Adel and South Shields). This shows the attachment of indigenous people to their roots and religious beliefs. The first one, discovered on the Roman site at Adel, north-west of Leeds (Yorkshire), is dedicated by a woman Cingetissa, whose name means ‘warrior’ or ‘attacker’.1172 It is engraved on a sandstone altar which has a serpent on its left side: Deae Brigan(tiae) d(onum) Cingetissa p(osuit), ‘To the goddess Brigantia, Cingetissa set up this offering’ (fig. 56).1173 The use of the formula dea indicates that the dedication is not prior to the mid-2nd c. AD.1174 The second altar, discovered in 1895 south of the fort at South Shields, Co. Durham, bears the following inscription: Deae Brigantiae sacrum Congenn(i)ccus u(otum) s(olvit) l(ibens) m(erito), ‘Sacred to the goddess Brigantia, Congennicus willingly and deservedly fulfilled his vow’ (fig. 56).1175 On the back of the altar is engraved a bird, on the right side a patera* and on the left side a jug; elements which may represent the functions of fertility of the goddess. The name of the dedicator Congennicus is Celtic and appears in other inscriptions from Narbonne and Nîmes.1176

Brigantia’s name is undeniably Celtic. It comes from the Gaulish word briga, cognate with Old Irish brí, Cornish, Welsh and Breton bre, ‘hill’, denoting highness and designating a high place, that is a hill or a mount.1177 These words come from an Old Indo-European adjective *bherĝh signifying ‘high’. By extension, the word briga, brigant- took on the significance of ‘fortified mount’ or ‘hill fort’, describing then the mount where the tribes had settled and built their fortified city. For instance, the oppidum* situated on Mount-Avrollot, overhanging the city of Avrolles (Yonne), was called Eburobriga (‘Mount or Fort of the Yew’).1178 In a recent study, Juan Luis García Alonso demonstrated that briga was very frequent in Celt-Iberian toponymics.1179 Being far less attested in Gaul, Delamarre advances that briga may have had the same significance as the word dunum, ‘hill fort’ found in many a Gaulish place name, such as Lugdunum.1180

Brigantia is etymologically linked to the Matres Brigaecae, who are venerated in an inscription from Peñalba de Castro, in Celtic Hispania: Ma(tribus) Brigaecis Laelius P[h]ainus v(otum) s(olvit) l(ibens) m(erito), ‘To the Mothers Brigeacae Laelius Phainus paid his vow willingly and deservedly’.1181The epithet of the Matres is clearly composed of the root brig-, ‘high’ and of the suffix –ko, which is probably localizing.1182

Brigantia is also related to the goddess Brigindona, honoured in a dedication engraved on a stone found in re-employment* in the building of an old funerary vault in Auxey (Côte d’Or), in the territory of the Aedui. The inscription is in Gaulish language and Latin lettering: Iccavos Oppianicnos ieuru Brigindon cantalon, ‘Iccauos son of Oppianos offered (this) cantalon (circular monument or pillar) to Brigindona’ (fig. 57).1183 As the name Brigindona is not preceded by the word dea ‘goddess’, it is difficult to determine whether Brigindona is a divine or proper name. However, the use of the dedicatory verb IEVRV, similar to Gallo-Greek ειωρου and signifying ‘(who) offered’ or ‘(who) dedicated’, is revealing.1184 Inscriptions or monuments were usually offered and dedicated to deities rather than to people. As the inscription was discovered at the bottom of the plateau of Montmélian, the worship of Brigindona (‘The High One’) must have been in relation to this mount. A Gaulish city might have been situated on this hill, but no archaeological data evidencing such a theory have been discovered so far.1185 Lacroix specifies that Brigindona’s name may have survived in the toponym* Brigendonis, the ancient name of the city of Brognon or Broindon (Côte d’Or), situated about 40 kms from Auxey.1186

British Brigantia, Celtiberian Matres Brigiacae and Gaulish Brigindona are etymologically related to the Irish goddess Brigit; the loss of unstressed ‘n’ in such words being typical of the Irish variety of Celtic. Brigit is described in the Lebor Gabála Érenn [‘The Book of Invasions’] as the daughter of the Dagda and listed among the Tuatha Dé Danann.1187 Very little information about Brigit has survived in Irish mythology. In Cath Maige Tuired, she is said to be the wife of Breas (‘Brave’), with whom she begot a son called Ruadhán (‘Red-Haired’).1188 When her son was murdered by Goibhniu the Smith, she wept him and gave thus the first lament (caoineadh) of Ireland. This legend clearly illustrates her in her role of mother-goddess. Sanas Cormaic [Cormac’s Glossary], dated c. 900, gives a hint of her functions and describes her as a threefold goddess. She is said to have had two sisters of the same name fulfilling specific roles:

‘Brigit .i. banfile ingen in Dagdae. Isī insin Brigit bē n-ēxe .i. bandēa no adratis filid. Ar ba romōr 7 ba roán a frithgnam. Ideo eam deam uocant poetarum. Cuius sorores erant Brigit bē legis 7 Brigit bē Goibne ingena in Dagda, de cuius nominibus pene omnes Hibernenses dea Brigit uocabatur.Brigit, i.e. lady poet, the daughter of the Dagda. It is she who was Brigit the woman of poetry, i.e. the goddess whom the poets adored. Because very great and very famous was her protection. Accordingly, they call her the goddess of the poets. Whose sisters were Brigit the woman of curing and Brigit the woman of smith craft, daughters of the Dagda, from whose names among all the Irish a goddess was called Brigit.1189 ’

In this text, Brigit appears as a goddess who possesses filidhecht, that is ‘poetry, divination and prophecy’, and protects poets. The two other Brigits respectively preside over medicine and metal work. The three Brigits are the triplication of the very same figure.1190 As studied in Chapter 1, triplism emphasizes and sublimates the various abilities and powers of the gods. Brigit is thus the patroness of arts, crafts and healing. In view of those attributes, it can be assumed that the word briga could have taken on a different meaning. In addition to its original geographical dimension, briga must have had a figurative sense as in Irish brí, signifying ‘vigour’ or ‘meaning’. It must have denoted force, vigour, nobility and sacredness, especially when referring to deities.1191 It is also interesting to note that briga is the same word as Sanskrit brhatī and Avestic bərəzaiti, signifying ‘high’ or ‘noble’.1192 It gave terms referring to kinship and nobility in the Celtic languages, such as Old Welsh breenhin, ‘king’, Cornish brentyn, ‘noble’ and Old Breton brientin, ‘noble person’. Therefore, the goddess names Brigantia, Brigit, Brigindona and Matres Brigiacae can be glossed either as ‘the High or Eminent Ones’ or ‘the Noble or Exalted Ones’.1193 Highness can thus refer to a high place or to the spirituality of the soul. By their summit rising toward the sky, mounts and mountains stand out in the landscape and compel respect and sacredness. It is thus not surprising that highlands became invested with spirituality and exaltation.

All those occurrences show that Ireland, Britain, Gaul and Celtic Hispania shared the worship of a ‘High, Exalted’ goddess. Brigit being described as a goddess of arts and crafts in Irish mythology, she is likely to correspond to the goddess Minerva, mentioned by Caesar in Book 6 of De Bello Gallico [The Gallic War] as one of the five deities honoured by the Gauls. He indeed stipulates that Minerva has the knowledge of craftsmanship and bestows it on her people:

‘Deum maxime Mercurium colunt. Huius sunt plurima simulacra: hunc omnium inventorem artium ferunt, hunc viarum atque itinerum ducem, hunc ad quaestus pecuniae mercaturasque habere vim maximam arbitrantur. Post hunc Apollinem et Martem et Iovem et Minervam. De his eandem fere, quam reliquae gentes, habent opinionem: Apollinem morbos depellere, Minervam operum atque artificiorum initia tradere, Iovem imperium caelestium tenere, Martem bella regere.1194They worship as their divinity, Mercury in particular, and have many images of him, and regard him as the inventor of all arts, they consider him, the guide of their journeys and marches, and believe him to have very great influence over the acquisition of gain and mercantile transactions. Next to him they worship Apollo, and Mars, and Jupiter, and Minerva; respecting these deities they have for the most part the same belief as other nations: that Apollo averts diseases, that Minerva imparts the invention of manufactures, that Jupiter possesses the sovereignty of the heavenly powers; that Mars presides over wars. To him when they have determined to engage in battle, they commonly vow those things they shall take in war.1195 ’

As we know, the Roman goddess Minerva also possesses the ability of healing. She was venerated in Rome with the epithet Medica (‘the Physician’).1196 This is another quality that Minerva shares with Brigit, who is said to preside over curing. Minerva is also a goddess of war in Roman mythology1197 and the goddess Brigantia, equated with Victory in three inscriptions and represented as a warrioress in a relief* from Birrens (Dumfries and Galloway, Scotland),1198 has a pronounced war-like aspect.

As for the possible connection between the goddess Brigit and Saint Brigit (later, Brighid) of Kildare (c. AD 439 - c. 524), whose cult was widespread in Ireland, Scotland, Wales, Cornwall, the Isle of Man and Brittany, it will not be considered in detail here, but it can be noted that on account of the similarity in names, feasts, attributes and functions, some scholars believe that the goddess and the saint were one, while others take them for two different characters.1199 Green even challenges the historicity of the Saint, arguing that:

‘Although Brigit is said to have been the founder-abbess of Kildare, there is no firm evidence for the abbess as a historical figure; descriptions of her life are based almost entirely on legend, which gives rise to the suspicion that she may be a mythic figure who underwent a humanisation-process and was thus endowed with a false historicity.1200 ’On account of their name, the syncretism between the two characters must have been uncomplicated and inevitable. Some attributes and functions of the ancient goddess, such as healing, the protection of farm animals and Imbolc, the 1st February Irish feast, were associated with Saint Brigit in later times and survived in her imagery. It is most likely, in fact, that the saint and the goddess are two different characters: one a mythical personage, while the other is recorded as a historical saint who was traditionally claimed to have founded the convent at Cill Dara (Kildare) and to have died in the year 524 AD. From that time onwards, many miracles and legends were attributed to her.1201 She would have been known in living memory for at least two generations after her death. The earliest reference to her is in a text which has been dated on linguistic evidence to the 6th c. AD. It occurs in the form of a prophecy, in a somewhat obscure rhetorical style, in a genealogical tract concerning the Fotharta people in Leinster.1202 The prophecy is represented as given to a fanciful prehistoric chieftain Eochaidh Find, brother of the mythical Conn Céadchathach, and it therefore reflects an attempt by the Fotharta to present themselves as related to the Tara kings. The prophecy is the following:

‘Cain gein cain orddan iartain dodoticfa dit genelgib clann. Condingerthar dia mor-buadaib Brig-eoit fhir-diada. Bid ala-Maire mar-Choimded mathair.A fair birth, fair dignity, afterwards which will come to you from your children's progeny. Who will be called due to her great virtues Brig-eoit the truly holy. She will be another Mary, of the great Lord the mother.1203 ’

Although an invention of the 6th c., this text would imply that Brigit (Brig-eoit) was well-known at that time, perhaps recently deceased. It would hardly make sense to people unless it referred to a real person who was known, or had been known recently, to the listeners. All the other texts, such as the c. 650 AD Vita Brigitae by the priest Toimtenach – who used the pen name Cogitosus - are however replete with legendary and unhistorical stories of the deeds and miracles of the saint.1204 Some of these deeds and miracles may indeed be fallout from the lore of the goddess.