2) Folk survivals

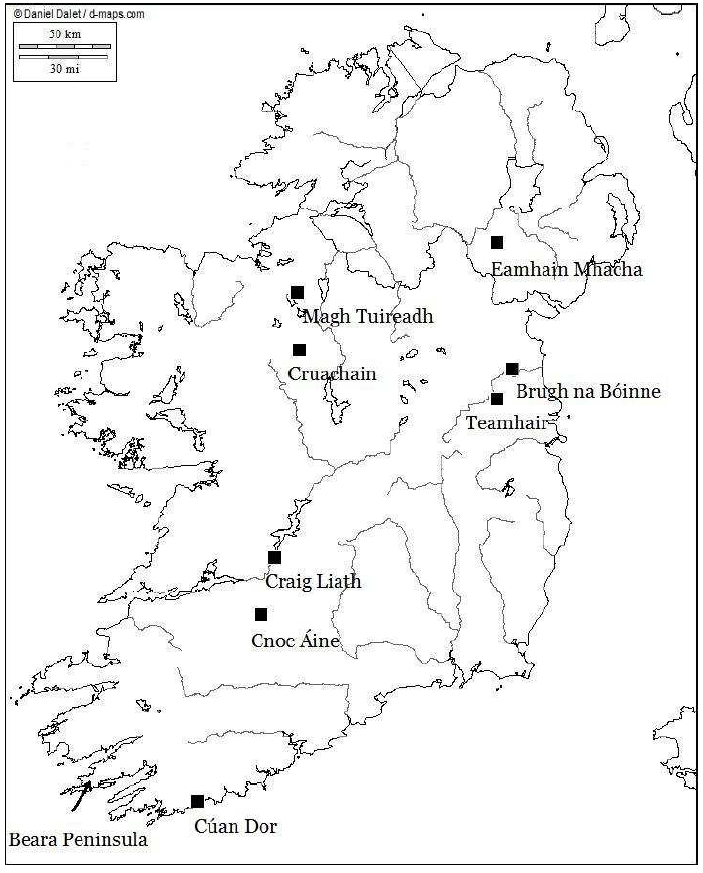

The character ofMór Muman endured in various folk accounts, particularly in County Kerry, and her character of sovereignty over the territory survived in several other preternatural ladies who were later attached to specific parts of the land of the province of Munster. Clidna, whose name means ‘the Territorial One’, is associated with Cúan Dor, the bay of Glandore, in Co. Cork, where she was said to have drowned (fig. 4).1305 Her dwelling is believed to be situated under a rock called Carraig Chlíona in the parish of Kilshannig, to the south of Mallow, in Co. Cork. Through oral lore, her cult extended to the whole of Munster and she became one of the most important and famous otherworld patronesses of the province. As her name indicates, Cailleach Bhéarra (‘the Hag of Beara’), also called Boí (‘Cow’) or the sentainne (‘old woman’) of Beara, is related to the Beara Peninsula, located between Bantry Bay and the Kenmare estuary, in the west of Co. Cork (fig. 4).1306 In literature and folklore, Cailleach Bhéarra is generally featured as an old and sinister woman, representing the dark side of the land-goddess. She is clearly associated with the land, agriculture and harvest time, configurating the landscape with her fingers and bringing prosperity to the province.1307 Her aspect of sovereignty is reflected in an 8th-century or early 9th-century poem, entitled ‘The Lament of the Old Woman of Beare’, relating she had drunk mead and mated with the kings of Ireland in her youth (see Chapter 5).1308 In Scottish folklore, she is known as Cailleach Bheur (‘the Genteel Old Woman’), and her counterpart is Cailleach Beinne Bric (‘the Old Woman of Speckled Mountain’). Moreover, she has some connections with Scottish winter spirits also represented as hags, such as Cailleach Uragaig (‘Old Woman of Uragag’) of the Isle of Colonsay (Strathclyde), and Caillagh ny Groamagh (‘Old Woman of Gloominess’). There was a similar hag called Caillagh ny Gueshag (‘Old Woman of the Spells’) on the Isle of Man.1309

The fairy lady Aoibheall (‘Sparkling’ or ‘Bright’), who is studied later in this chapter, presided over the territory of east Co. Clare and north-west of Co. Tipperary and protected the sept* of the Dál gCais (O’Briens), who had a stronghold built on the rock Craig Liath (Craglea, near Killaloe, Co. Clare) in the 6th c. AD (fig. 4).1310 The legends make this promontory the dwelling of Aoibheall. Finally, the fairy lady Áine, whose name signifies ‘Brightness’, ‘Glow’ or ‘Lustre’, is specifically attached to Cnoc Áine (Knockainey), a hill located near Lough Gur in east Co. Limerick (fig. 4).1311 She was one of the patronesses of the tribe of the Eóganacht. She is either identified as the daughter of the sea god Manannán mac Lir,1312 or as the daughter of the fairy king Eógabal.1313 She is generally described as a beautiful radiant fairy lady, as in the poem entitled Bend Etair, published in the Metrical Dindshenchas, which relates that Etar pined for her and died of a broken heart when he was rejected.1314 Áine’s territorial and sovereign aspect is clearly emphasized in a passage of an 8th-century text, entitled Cath Maige Mucrama [‘The Battle of Mag Mucrama’].1315 The legend recounts that Ailill, after falling asleep twice at Samhain on Cnoc Áine, wondered who had stripped the grass of the hill during the night and came to inspect the mount with the help of Fearcheas mac Comáin, a seer-poet.1316 They discovered that fairy people inhabited the hill: the king Eógabal and his daughter Áine. Fearcheas murdered Eógabal and Ailill abused the girl, who cursed him for misconduct. From that time on, the name of Áine was given to the hill.1317 The text as we have it from the 8th c. goes as follows:

‘Luid Ailill íarum aidchi shamna do [fh]recaire a ech i nÁne Chlíach. Dérgither dó is’ tilaig. Ro lommad in tilach in n-aidchi-sin 7 ni fes cía ros lomm. Fecht fo dí dó fon inna[s]-sin. Ba ingnad les-seom. Foídis techta úad co Ferches mac Commáin éices ro baí i mMairg Lagen. Fáith side 7 fhénnid. Do-lluid-side dia acallaim. Tíagait a ndiis aidchi shamna issin tilaig. Anaid Ailill is’ tilaig. Baí Ferches frie anechtair. Do-fuitt didiu cotlud for Ailill ic costecht fri fogilt na cethrae. Do-llotar asint síd 7 Éogabul mac Durgabuil rí int sída ina ndíaid 7 Áne ingen Éogabuil 7 timpán créda ina láim oca seinm dó ara bélaib. At-raig dó in Ferches co toba(i)rt buille dó. Ro ráith Éogabul reme issa síd. Atn-úarat Ferches di gaí mór co rróemid a druim triit. In tan donn-ánic co Ailill cond-ránic-side frisin n-ingin. Eret ro buí i ssuidiu ro den in ben a ó cona farcaib féoil na crocand fair connáro ássair fair ríam ónd úair-sin. Conid Ailill Ó-lomm a ainm ó sein. ‘Olc ro bábair frim’, ar ind Áne, ‘mo sárugud 7 marbad m’athar. Not sáraigiub-sa ind .i. nocon fháicéb-sa athgabáil latt in tan immo-scéram’. Ainm na ingine-sin fil forin tilaig, .i. Áne Chlíach.Ailill went then one Samhain night to attend to his horses on Áne Chlíach. A bed is made for him on the hill. That night the hill was stripped bare and it was not known who had stripped it. So it happened to him twice. He wondered at it. He sent off messengers to Ferches the poet son of Commán who was in Mairg of Leinster. He was a seer and a warrior. He came to speak to him. Both go one Samhain night to the hill. Ailill remains on the hill. Ferches was aside from it. Sleep then comes to Ailill while listening to the grazing of the beasts. They came out of the fairy mound with Éogabul son of Durgabul king of the fairy mound after them and Áne daughter of Éogabul with a bronze timpán in her hand playing before him. Ferches rises up to meet him and struck him. Éogabul ran on into the fairy mound. Ferches attacks him with a great spear so that his brack broke when he reached the fairy mound. Ailill had intercourse with the girl. While he was so engaged the woman sucked his ear so that she left neither flesh nor skin on it and none ever grew on it from that time. So that Ailill Bare-ear is his name since then. ‘You have been wicked to me’, said Áne, ‘[in] violating me and slaying my father. I will cause great injury to you for it. I will leave no property in your possession when we part’. That girl’s name is on the hill, that is, Áne Chlíach.1318 ’

The form of the relationship between Ailill and Áine – rape rather than marriage – reflects a hostile twist to the tradition, and properly the lore must have been that Ailill became the husband of the land-goddess Áine. Because of this connection with Ailill Ólom, the mythical king of the Eóganacht, Áine became viewed as the ancestress of the sept*, and because of her relation with the territory of this tribe, she is clearly an emanation of the ancient Munster land-territorial goddess of sovereignty. Her name cannot however be etymologically related to the name of the land-goddess Ana, as Eleanor Hull stipulates in Folklore of the British Isles.1319

The Irish mythological and folk legends thus reflect several aspects of early tradition. First of all, it is clear that each tribe worshipped particular goddesses embodying the land where they had settled. Each province of Ireland, ruled by different peoples, became represented by a distinctive goddess: Medb Lethderg presided over Leinster, the land of the Laighin, Medb Cruachan ruled Connaght and the Connachta, Macha (the Mórrígain) protected Ulster and the Ulaid and Mór Muman, the patroness of the Érainn, guarded over Munster. As demonstrated in Chapter 2, those goddesses clearly have land and agrarian aspects: Macha is the ‘Field’, Mór Muman is the ‘Great Nurturer’, etc. They are all emanations of the primary goddess embodying the land and bringing fertility, prosperity and wealth to the people. Becoming attached to certain parts of the territory, inhabited by septs* of different origins, the earth-goddess took on different names and various functions were attributed to her.

What emerges from the legends is the role of sovereignty pertaining to the territorial or tribal-goddesses. As her title proves, Queen Medb, who subdues kings and heroes, is the sovereign par excellence. The accounts of Medb Lethderg, Medb Cruachan, Macha and Mór Muman are reminiscent of the archaic belief of the land-goddess mating with the sky-father god, illustrated by the legend recounted in Cath Maige Tuired of the Dagda (‘Good God’) and the Mórrígain (‘Great Queen’), who couple at the ford of the river Uinsinn, in Co. Sligo, right before the beginning of the mythical battle between the Tuatha Dé Danann and the Fomhoire: Medb Lethderg, Medb Cruachan, Macha and Mór Muman clearly accede to the sovereignty of the territory by coupling with the reigning kings. The text is the following:

‘Boí tegdas den Dagdae a nGlionn Edin antúaith. Baí dano bandál forsin Dagdae dia blíadhnaehimon Samain an catha oc Glind Edind. Gongair an Unius la Connachta frioa andes. Co n-acu an mnaí a n-Unnes a Corand og nide, indarna cos dí fri Allod Echae (.i. Echuinech) fri husci andes alole fri Loscondoib fri husce antúaith. Noí trillsi taitbechtai for a ciond. Agoillis an Dagdae hí 7 dogníad óentaich. Lige ina Lánomhnou a ainm an baile ó sin. Is hí an Morrígan an bhen-sin isberur sunn.The Dagda had a house in Glen Edin in the north, and he had arranged to meet a woman in Glen Edin a year from that day, near the All Hallows of the battle. The Unshin of Connacht roars to the south of it. He saw the woman at the Unshin in Corann, washing, with one of her feet at Allod Echae (i.e. Aghanagh) south of the water and the other at Lisconny north of the water. There were nine loosened tresses on her head. The Dagda spoke with her, and they united. ‘The Bed of the Couple’ was the name of that place from that time on. (The woman mentioned here is the Mórrígain.1320 ’

The evidence in Gaul and Britain of goddesses bearing ethnonyms* or names of tribes, such as Brigantia of the Brigantes, Dexiva of the Dexivates, the Matres Treverae of the Treveri, the Nervinae of the Nervinii, the Matres Remae of the Remi, the Matres Senonae of the Senones, the Matronae Vediantiae of the the Vediantii, prove that the worship of tribal-goddesses was part of the religious beliefs of the Celts. The Irish territorial-goddesses are not eponymous of the sept* they represent, but their stories shed light on the possible nature and functions of the Gallo-British tribal-goddesses. As primary land and agrarian goddesses, they ensure prosperity to the province and its inhabitants. As representatives of the tribe, they preside and rule over the territory and people; a sovereign role which leads to a significant function of protection and defence of the land. The Irish mythological legends indeed evoke the pronounced war-like character of the territorial/tribal-goddesses. Thus, Macha rises up in arms and fiercely fights to gain queenship, while Medb declares war on the Ulstermen to obtain the great bull of Cooley. Furthermore, Medb Lethderg (‘Half-Red’), Medb Cruachan (‘Bloody Red’) and Macha Mong Ruad(‘Red-Haired’) bear epithets referring to the colour red, which symbolises blood and war, as Dumézil points out: “red was the colour of war and warriors for the Celts, as well as in Rome and in India”.1321 Those epithets are accordingly redolent of the bloody contests which occurred to obtain the power of a province.

In addition to her function of sustenance, the goddess presiding over the land and the tribe was given regal and martial attributes, conveying protection of the territory and its inhabitants. This role is clearly illustrated by the British goddess Brigantia, tutelary goddess of the Brigantes, who is portrayed with helmet and spear on a relief* from Birrens (Dumfries and Galloway, Scotland),1322 and equated with the Romanized goddess Caelestis, to whom was attributed protective functions of the city, and the Roman goddess of war Victory in three inscriptions from Corbridge and Yorkshire (see below).1323 The land-goddess was thus turned into a war-goddess when protection was needed in time of conflict.