A) Divine Crows of War: Badb, Cathubodua and Cassibodua

The name of the crow-shaped war-goddess Badb, later Badhbh, derives from Celtic boduos, bodua, which must originally have had a connotation of fury, rage and violence and signified ‘fight’.1328 As Lambert argues, it may be derived from *bhu-dh-wâ, a participial formation in -wo-, -wâ, coming from the verbal theme *bheu-dh- meaning ‘to inform’, ‘to warn’, ‘to awaken’.1329 Badb would thus mean the ‘presage’ or the ‘prediction’. This theory is interesting, for the war-goddess clearly fulfils a role of prophetess and harbinger of death. Furthermore, the apparition of a crow is viewed in Irish mythological and folk traditions as a bad omen, foreshadowing disaster or death. The word bodb later evolved with the meaning of ‘raven’, ‘crow’ or ‘fighting lady’ because the war-goddess was represented in such a shape. As Badb appears in time of war and hovers over the carnage of the battlefield, she is often given the epithet of Cath which means ‘battle’ in Irish and is cognate with Welsh cad, Old Breton cat and Gaulish catu, ‘battle’.1330 The Cath-Bhadhbh or later Badb Catha is thus the ‘Battle Crow’. The Irish Cath-Bhadhbh indeed would linguistically go directly back to a Celtic *Catu-bodua.

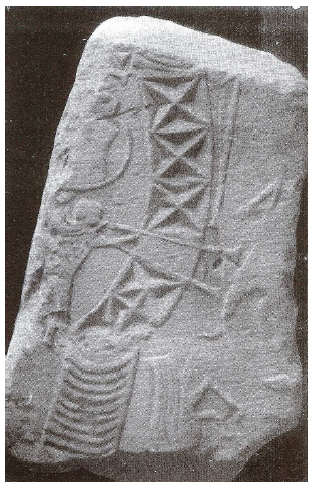

It is of great significance to find the exact same name in an inscription from the south-east of Gaul, discovered in a field called ‘Vers Fan’, at a place known as Les Fins de Ley, in the hamlet Ley, near Mieussy (Haute-Savoie) in 1860: [C]athuboduae Aug(ustae) Servilia Terentia v(otum) s(olvit) l(ibens) m(erito), ‘To the August Cathubodua, Servilia Terentia paid her vow willingly and deservedly’ (fig. 5).1331 The dedicator is a woman who has Latin names and bears the duo nomina of Roman citizens. Scholars are divided on the spelling and meaning of the name of this goddess. The altar being damaged on the left side, some specialists, such as Alfred Pictet, William Hennessy and Olmsted, maintain that the first letter of the name is missing. In view of Irish Cath-Bhadhbh, they reconstruct the divine name as [C]athubodua, ‘Battle Crow’ and see in her a war-goddess in crow shape.1332 Others, such as Allmer, Toutain and Bernard Rémy, deny the possibility of a missing letter and assert that the name is to be read Athubodua. According to them, the first element of her name athu can be related to the name of a nearby lake or swamp called Anthon, near the village of Anthon. Athubodua would therefore be the name of a topical goddess presiding over the waters of this lake.1333 Nonetheless, this etymology* does not take the second element bodua into account, and, as the altar is mutilated on the left side, the possibility of a missing letter cannot be dismissed.

At any rate, this Gaulish inscription proves that the belief in a raven-shaped goddess (bodua) certainly goes back to ancient times and was shared by various Celtic peoples. Significantly, Delamarre adds that there might have been some similarity between Irish Badb, Gaulish Bodua and an archaic Germanic goddess of war and storm called Baduhenna, whose name could be derived from a proto-Germanic root *badwa - meaning ‘battle’.1334 Tacitus, who recounts the revolt of the Germanic Frisians against the Romans at the end of Book 4 of The Annals, mentions that Baduhenna had a grove bearing her name in Frisia, where, in 28 AD, 900 Roman soldiers were slain by the Frisians:

‘mox compertum a transfugis nongentos Romanorum apud lucum quem Baduhennae vocant pugna in posterum extracta confectos, et aliam quadringentorum manum occupata Cruptorigis quondam stipendiari villa, postquam proditio metuebatur, mutuis ictibus procubuisse.Soon afterwards it was ascertained from deserters that nine hundred Romans had been cut to pieces in a wood called Baduhenna's, after prolonging the fight to the next day, and that another body of four hundred, which had taken possession of the house of one Cruptorix, once a soldier in our pay, fearing betrayal, had perished by mutual slaughter.1335 ’

![Fig. 5: Altar dedicated to [C]athubodua (‘Battle? Crow’) discovered in Mieussy (Haute-Savoie). In the Museum of Annecy. Hennessy, 1870, p. 32.](/documents/getpart.php?id=1266&file=10000000000001CC000002B83BD41E75.png)

Moreover, a goddess Cassibodua is mentioned in a dedication from Herbitzheim (Germany): I(n) h(onorem) d(omus) d(ivinae) Victoriae [C]assi(b)oduae, ‘In honour of the Divine House and to Victoria Cassibodua’.1336The use of the abbreviated votive formula In h. d. d. allows us to date this altar from the beginning of the 3rd c. AD.1337 The significance of the first element of her name cassi is still much debated. Various translations have been proposed, such as ‘elegant’, ‘full of hatred’, ‘saint or sacred’, and recently ‘tin’ or ‘bronze’, with a connotation of hardness or power and probably of brightness.1338 The second element of her name bodua refers to the ‘crow’.1339 Cassibodua might therefore be the ‘Sacred Crow’ or the ‘Strong, Powerful Crow’ (?). This goddess is undeniably related to war, since she is associated with Victoria, the Roman goddess who attends to the war successes of her people and ensures victory.1340

The existence of Irish Badb and Gaulish (C)athubodua and Cassibodua strongly suggests that the tradition of a war-goddess in the shape of a crow was extant in Celtic times. The texts describe the raven-shaped goddess flying over the field of battle and devouring the corpses of the dead soldiers. The 13th-century Glossary of O’Mulconry indeed specifies that Macha, that is Badb, eats the heads of the warriors slain in combat:

‘Machae .i. badb nó así an trés morrígan, unde mesrad Machae .i. cendae doíne iarna n-airlech.Macha, i.e. Badb, or it is she who is the third Mórrígain, therefore the fruit crop of Macha, the heads of men after the massacre.1341 ’

Where does this belief come from? The carrion-crow is a bird of prey which was seen hovering over the battleground after the carnage of a fight, waiting for the moment when it would satisfy its hunger with the flesh of the dead soldiers. Thus the crow became an important symbol of war for the Celts, as some helmets adorned with a raven illustrate.1342 A noteworthy example is the impressive iron helmet from Ciumesti (Romania), dated beginning of the 3rd c. BC, which is surmounted by a huge crow in bronze (fig. 6).1343 Similarly, on one of the plaques of the Gunestrup Cauldron, a warrior is featured wearing a crow-crested helmet (Chapter 5, fig. 8).1344

It is interesting to note that some Classical texts tell of a tradition in Celtic times not to bury the bodies of the dead warriors after the fighting but to leave them on the battlefield to be devoured by carrion crows or birds of prey.1345Such a practice is recounted by Pausinias in around AD 180, in his Description of Greece (Graciae Descritpio), which tells of the incursion of the Celtic chief leader Brennos into Greece, through the pass of Thermopylae ‘Hot Gates’ to reach the centre of Greece from Thessaly:

‘touto men dê epegegrapto prin ê tous homou Sullai kai alla tôn Athênêisi kai tas en têi stoai tou Eleutheriou Dios kathelein aspidas: tote de en tais Thermopulais hoi men Hellênes meta tên machên tous te hautôn ethapton kai eskuleuon tous barbarous, hoi Galatai de oute huper anaireseôs tôn nekrôn epekêrukeuonto epoiounto te ep' isês gês sphas tuchein ê thêria te autôn emphorêthênai kai hoson tethneôsi polemion estin ornithôn.This inscription remained until Sulla and his army took away, among other Athenian treasures, the shields in the porch of Zeus, God of Freedom. After this battle at Thermopylae the Greeks buried their own dead and spoiled the barbarians, but the Gauls sent no herald to ask leave to take up the bodies, and were indifferent whether the earth received them or whether they were devoured by wild beasts or carrion birds.1346 ’

Similarly, the Greek sophist Aelien, in his De Natura Animalium (200 AD), speaking of the Vaccaei, a people from the north-east of Spain, and the Latin poet Silius Italicus in Punica (50 AD) - an important work which recounts the events of the Second Punic War, from the oath of Hannibal to the victory of Scipion at the end of the war at Zama - explain that the Celt-Iberians used to leave the bodies of the warriors killed in action on the ground in open air, so that the birds of prey, which were regarded as sacred, could eat their flesh and entrails:

‘The Vaccaei burn the bodies of those who are dead of illness on a pyre […] Those who are dead in war, and who they regard as noble men of high value, they abandon them to the vultures, which they regard as sacred.1347The Celt-Iberians came after them. Eager to die in battle, they consider it a crime to burn the body of those who die in this fashion. They believe that their souls return to the heavens and the realm of the gods, if their corpses are torn to pieces by the greedy bird of prey.1348

In Celt-Iberia, there was an ancient custom of leaving dead bodies to be devoured by the foul bird of prey.1349 ’

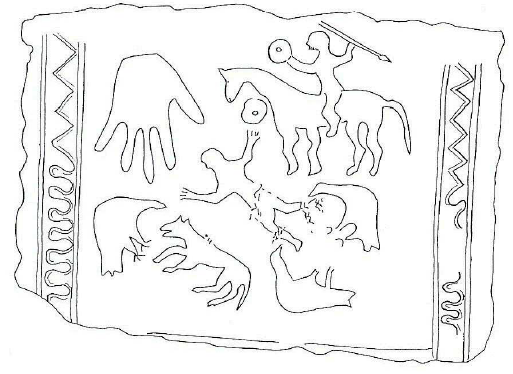

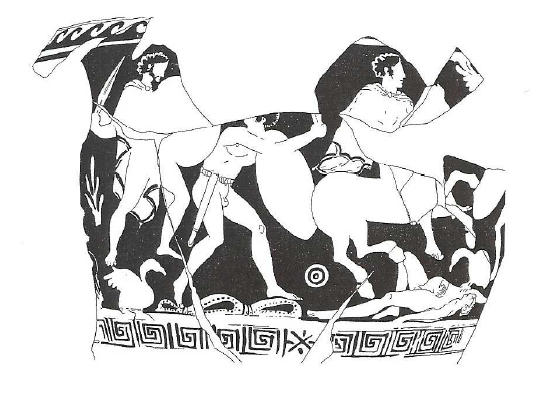

In addition to being mentioned in some passages of Classical literature, the Celtic funerary practice of exposing the bodies of the dead warriors to the birds of prey is attested in the iconography, notably from Celtiberia. A fragment of stele* discovered in Lara de los Infantes (Burgos, Museo Arqueológico) depicts a scene of war. On the left, two soldiers play music on long trumpets. On the right, from top to bottom, a spear or javelin, a standing warrior with a sword, a head of spear and a huge bird which may be a crow can be identified (fig. 7).1350 Two fragments of painted ceramic from Numantia - a city situated in the north of Spain which resisted the Romans from 143 to 133 BC - show two warriors lying on the ground flown over by birds of prey.1351 Moreover, a stele* from El Palao, in the Alcañiz region (Teruel), is of great interest, for it has a rider holding a spear in his left hand and a round object in his right hand. At his feet, the body of a dead warrior, who holds the same round object in his left hand, lies and is being eaten by two ravens (fig. 8).1352 Finally, Jean-Louis Brunaux refers to a stamnos*, dating from the 1st quarter of the 4th c. BC, housed in the Kunstmuseum in Bonn, which represents two Celtic warriors fighting two Italic soldiers (fig. 9).1353 The Celtic warriors are recognizable because they are combating naked and because they wear a belt holding a typical La Tène sheath. The one on the right is dead and lies on the ground. A bird of prey, perched on his shoulder, devours the flesh of his stomach. A second vulture, situated behind the fighting warrior, seems to be waiting for his death: the bird of prey, which is an omen of death, represents the impending death of the warrior.

This has a clear parallel with the episode of the death of the great Irish hero-warrior Cú Chulainn, recounted in a text entitled Aided Con Culainn [‘The Death of Cú Chulainn’]. The text dates from the 14th or 15th c., but the stratum of the legend is previous to the 10th c.1354 It relates that the death of Cú Chulainn was brought about by the six children of Cailitín, a warrior slain in combat by the hero. Medb had these children reared by a sorceress in the faraway regions of the world, and they returned to Ireland determined to use their magic to avenge their father’s death. One of these children was the sorceress called Badb:

‘[…] 7 do bí a inathar rena chosaibh ann sin, 7 do thúirn in branfiach Badhbha forsna hindaibh, co tarrla camlúb dona cáelánaibh fo chosaibh in brainfhiaigh, co tarrla leagad dó. 7 do maidh a gean gáire for Coin Chulainn uime sin 7 is é sin gáire deidhenach do-rinne Cú Chulainn. Et tángatar neóill in bánéga dá innsaighi ann sin 7 táinic roime chum locháin do bí a coimnesa. Do bí ’ga thonach féin as, gurob Lochán in Tonaigh ainm in locháin dá éisi.[…] and his intestines were about his legs then, and the raven Badhbh descended on the place, so that a twisted loop of the guts happened to be under the legs of the raven, so that it was knocked down. And his merry laugh came to Cú Chulainn at that, and that was the last laugh done by Cú Chulainn. And the shades of white death came over him then, and he went to a pool which was nearby. He was washing himself from it, and accordingly that pool is named Lochán an Lonaigh [i.e. ‘the Pool of the Washing’] after that.

‘Cáit a fuil Badhbh ingin Cailitín ?’ ar Medb.

‘Atú sund’, ar Badhbh.

‘Éirigh,’ ar Medb, ‘7 fagh a fis damh in beó nó in marb Cú Chulainn.’

‘Rachadsa and sin,’ ar Badhbh, ‘gidh b’é olc dogébh de.’

Is é richt a ndechaidh a richt eóin ar eittillaig annsan áer ósa chind, 7 ‘má tásan beó, marbhfaidh sé misi don chéturchar asa chranntabhull, óir ní dechaidh én ná bethidheach etorra 7 áer nar marbhfad, 7 má tá marbh, do-gén túrnamh ara chomair, 7 do cluinfid sibhsi mo chomarc.’

7 táinic a richt fuince .i. fennóigi a frithibh forarda na firmaminti ósa cind, 7 do druit anuas d’éis a chéile no co ráinic a comgaire dó, 7 do léig a trí sgrécha comóra ósa chin, 7 do thúirn arin sceich ósa comair amach, conadh sceich fuinci ainm na sceiche ar Mag Muirthemne.

Ó ’d-chonncatar fir Érenn sin, ‘is fír sin,’ ar siat, ‘is marbh Cú Chulainn 7 innsaighther dúin é.’

‘Where is Badhbh, daughter of Cailitín?’ said Meadhbh.

‘I am here,’ said Badhbh.

‘Arise,’ said Meadhbh, ‘and get knowledge for me whether alive or dead is Cú Chulainn.’

‘I will go there,’ said Babhdh, ‘even though I fare badly due to it.’

The form she went in was that of a bird flying in the air over him, and ‘if he be alive he will kill me with the first shot from his sling, for no bird or animal [ever] went between him and air that he would not kill, and if he is dead I will descend in front of him, and ye will hear my outcry.’

And she came in the form of a crow i.e. of a scaldcrow from the very high realms of the firmament over him, and she came down gradually until she came near to him, and she gave her three great screeches over him, and she descended onto the thorn-bush in front of him, so that the thorn-bush on Magh Muirtheimhne [‘the Plain of the Inundation’] is named the thorn-bush of the crow.

When the men of Ireland saw that, ‘it is true for you,’ they said, ‘Cú Chulainn is dead, and let us approach him.’1355 ’

This is a fictional development of Badb into a daughter of Cailitín, but she retains the earlier mythical connotation of the otherworld woman who is hostile to Cú Chulainn: the Mórrígain or Badb. The text is reminiscent of her early crow-shaped image and shrieks. It recounts that Badb first came to Cú Chulainn to drink his blood when he was cleaning his wounds in a lake after the fighting. She tripped over his entrails, which made him laugh one final time. Cú Chulainn strapped himself to a stone column, so that, even in death, he would face his enemies standing. Badb is then sent by Medb to check whether the great hero is dead.

This funerary custom might be also attested by archaeological discoveries. Brunaux suggests that the polygonal enclosure of the war sanctuary of Ribemont-sur-Ancre (Somme), situated about forty metres from the quadrangular enclosure, may have been used as a door towards the otherworld, where the corpses of the dead warriors of the victors were deposited in open air at the mercy of the birds of prey for their souls to be taken to the Beyond.1356 The enclosure was paved and delimited by high walls in wood and cobs. In the north part of the enclosure, a two-metre-deep hollow altar and a significant amount of carcasses of domestic animals which attest to intensive religious practices and rituals were unearthed. The excavations indicated that, after a few months, the walls had been destroyed and the trenches filled in with the remains of the pavement, burnt wood and vestiges from the enclosed area. These vestiges turned out to be a hundred human bones and weapons, which means that corpses had been left to decompose in the yard, where religious rites must have been held, before filling up the ditch. Given that some of the bones have marks of animal manducation, Brunaux assumes this might have been a death rite consisting in letting the vultures devour the flesh of the dead warriors to facilitate their travel to the otherworld.1357 Unlike the quadrangular enclosure, the bones were not those of the enemy warriors but of the winning camp. About fifty one-metre high steles* in sandstone in the effigy of warriors were indeed discovered on the site. They must have represented the hero-warriors who had courageously fought: their bravery had to be eternally glorified. This funerary rite must have been accompanied with religious ceremonies and practices, which would explain the various animal sacrifices and the hollow altar. The priests were present to establish contact with the otherworld and to ease the transition of the heroes to the supernatural world. Furthermore, offerings were made so that the gods would accept and look after them.

Therefore, it is clear that the crow shape of the war-goddess springs from the fact that birds of prey were often seen flying over the carnage at the end of a combat. It is natural for such birds to feed on the flesh of dead bodies. The birds were generally regarded as divine messengers or oracular birds commuting between the realm of the gods and the natural world, predicting events or answering the questions of the human beings.1358 In the context of war, the mediator of the gods took on funerary aspects, being then understood as a conveyor of the souls of the glorious dead warriors to the otherworld. This is attested by some Classical texts, iconographical data and possibly archaeological discoveries, such as the polygonal enclosure of Ribemont-sur-Ancre (Somme). The bird of prey was then deified as a goddess taking its shape and cries, flying over the battlefield, taking part in the carnage and exulting in bloodshed. As the Classical authors explain, it was honourable for the Celts to die in war. It was a proof of courage, valour and great merit for the warrior who gave his life for the protection of his people. Not to bury the dead heroes but to leave them in the open air was a mark of high respect, for the warriors, eaten by the crow goddess, would be taken to the divine world and eternally praised.