B) The ‘Queen’ Goddess: Irish Mórrígain, Gallo-British Rigana, Welsh Rhiannon

The meaning of the name of the most famous Irish war-goddess has caused a lot of ink to flow among the scholars, for its spelling differs from one text to another: Mórrígain / Mórrígu or Morrígain / Morrígu.1359 The second element of her name is unambiguous. In Old Irish, rígain means ‘queen’, like Welsh rhiain, which originally signified ‘queen’ but has today the meaning of ‘young lady, maiden, virgin’.1360 They are both derived from an old Celtic word rīgani / rīgana meaning ‘queen’, equivalent to Latin rēgīna. The endig in ‘u’ is due to analogy with other feminine words which have a genitive ending in ‘an’, as Mórrígain does (gen. sing. Mórrígan).As for the first element of her name, it is problematic, for it is sometimes written with a short vowel, i.e. mor meaning ‘phantom’ or ‘nightmare’,1361 and sometimes with an accented vowel, i.e mór meaning ‘great’.1362 This difference in spelling changes the significance of the goddess name.

Generally, the form Morrígain, that is ‘Phantom Queen’, is taken to be the earliest and primary form.1363 And yet, one is inclined to think that the form Mórrígain, that is ‘Great Queen’, is the correct spelling, given that the adjective mór is often used to qualify land-goddesses in Irish tradition, for instance Mór Muman (‘Great Nurturess’). Furthermore, it seems that the appellation ‘Great Queen’ is more suitable for a goddess than the designation ‘Phantom’, although this latter designation could refer to her link to death. The context of carnage and her function as an harbinger of death are of later date than her attributes of land-goddess, and this is the reason why we chose to spell her name Mórrígain rather than Morrígain.

Just as Irish Cath-Bhadhbh is similar to Gaulish Cathubodua, the Mórrígain is etymologically linked to the goddess epithet or name Rigani, which is attested in Latin form by three Gallo-Roman inscriptions discovered in Great Britain and Germany. The dedication found in Worringen (Germany), in the territory of the Ubii, reads: In h(onorem) d(omus) d(ivinae) deae Regin(ae) vicani se[...] Gorigienses, ‘In honour of the Divine House and of the goddess Regina, the inhabitants [...] Gorigienses’.1364 The one discovered before 1732 in Lanchester, located in the north-east of Britain, is engraved on an altar, which has a wild boar on the left side: Reginae votum Misio v(otum) l(ibens) s(olvit), ‘To the Queen-Goddess, Misio willingly fulfilled his vow’.1365 The dedicator Misio is a peregrine*, for he bears the unique name. The most interesting monument is the relief* from Lemington, a town situated a few kilometres north of Lanchester, because it offers an inscription combined with a depiction of the goddess: DEA RIIGINA.1366 The goddess is represented “with a halo coiffure and a robe reaching to the knee. In her left hand she holds a pointed staff resting on a stand, in her right hand a short staff resembling a cordoned column”.1367 These attributes bespeak her sovereignty and power, and might bear some war symbolism.

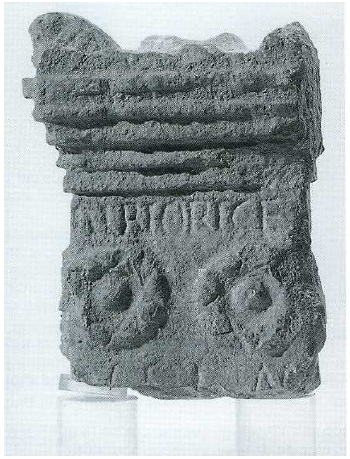

Other Gaulish goddess-names comprise the root riga, rica, ‘queen’: Camuloriga (‘Queen of the Champions’),1368 and possibly Albiorica, but her name is uncertain. An inscription engraved on a mutilated altar discovered around 1875 in Saint-Saturnin d’Apt (Vaucluse) reads: Albiorice v(otum) s(olvit) l(ibens) m(erito), ‘To Albiorice [the dedicator] paid his vow willingly and deservedly’ (fig. 10).1369 One could wonder whether Albiorice is a divine name or a proper name, but the use of the votive formula votum solvit libens merito indicates that the inscription is offered to a deity. Scholars are divided over the gender of the deity. Augustin Deloye and Otto Hirschfeld reconstruct the feminine name Albiorica, while Espérandieu, Barruol and Jacques Gascou argue that the form Albiorice stands for Albiorix.1370 While the goddess name Albiorica is not known from any other dedications, the god name Albiorix is mentioned in several inscriptions from Mont-Genèvre (Hautes-Alpes), Vaison-la-Romaine (Vaucluse) and Montsalier (Alpes-de-Haute-Provence).1371 The first element of his name albio, ‘bright’, ‘world (from the above)’ has a religious and mythological connotation and seems to refer to high places, such as mounts or mountains.1372 Albiorix (‘King of the World’) is imagistically the opposite of the proper name Dumnorix (‘King of the Under World’) which alludes to the world of darkness.1373 According to Sterckx, Albiorica may have been a healing goddess similar to the Roman goddess of health and hygiene Hygia, because her consort Albiorix is sometimes associated with Apollo in the inscriptions.1374 However, Albiorix is never attached to the god Apollo in the epigraphy,1375 and moreover, there is no archaeological data indicating a healing cult attached to Albiorica.

Rigani appears beside the name of Rosmerta on the Gallo-Latin graffiti from Lezoux either as a divine name referring to an individual goddess, or as an attributive byname* of Rosmerta, or as a word designating a real human queen.1376Regina is also given as an epithet to the goddess Epona in various inscriptions from present-day Bulgaria, Romania, Hungary and Croatia.1377 Rigani is itself cognate with god bynames*, such as Mars Rigas in Malton (GB),1378 Mars Rigisamus in Bourges (Cher) and West Coker (GB),1379 and Mars Rigonemetis (‘King of the Sanctuary’) in Nettleham (GB).1380

In addition to being mentioned in Irish mythology and Gallo-British epigraphy, the goddess termed Rigani also appears in Welsh medieval literature. One of the most important female mythological characters of the Mabinogi bears the name of Rhiannon, which comes from an old Celtic word *Rīgantonā, meaning the ‘Divine, Great Queen’.1381 The first branch of the Mabinogi, entitled Pwyll, recounts that Rhiannon, daughter of Hyfiid Hen, was given in marriage to Pwyll (‘Intelligence, Judgment’),1382 Prince of Dyfed, who had been mesmerized after seeing her riding on a white horse. His rival Gwawl, son of the goddess Clud, stole Rhiannon from him at his wedding-feast by tricking him. Pwyll then killed Gwawl to recover his fiancé. When Rhiannon’s son, Pryderi, was abducted on the night he was born (May Eve), she was accused of murdering him. He was in fact being reared by Teyrnon Twrf Liant, Lord of Gwent. Her punishment, which lasted seven years, consisted in waiting at the horse-block outside the palace gate and offering a ride on her back to any visitor. In the third branch, entitled Manawydan, Pryderi became King and Rhiannon married Manawydan after Pwyll’s death. The kingdom was then devastated by a mystical fog, which was cast by Llwyd the magician, who was seeking revenge for Gwawl’s murder. After being imprisoned in Annwyfn for a long time, Rhiannon and Pryderi were eventually freed by Manawydan. Rhiannon thus perfectly fulfils the role of sovereign implied by her name.