B) Figurations on Coins: Human or Divine Warrioresses?

Several figurations on Gaulish coins are worth studying and analyzing. They all represent naked women who ride galloping mounts and possess martial attributes, such as the cart, the shield, the spear and the hilt of a knife. The certainty of the femininity of those riders resides in the fineness of the torso, the thinness of the arms and the round breasts, which clearly appear on the facsimiles.

A golden coin, probably dating from the 2nd c. BC, from the département of Loire, in the territory of the Turones, bears the representation of a woman, hair streaming in the wind, who stands on a cart, symbolized by a wheel, and holds the reins of a galloping horse (fig. 13).1451 The female charioteer wears a small skirt and brandishes an unidentifiable stick, probably a weapon, towards the front of the steed. Because of the gonfalon* flying on the right of the horse, Duval asserts that the charioteer is depicted entering the fray.

Third-century BC golden coins from the area of Rennes (Ille-et-Vilaine), in the territory of the Redones, have a naked woman riding a galloping steed without a saddle on the obverse (fig. 14).1452She brandishes a shield in her left hand, and a spear with two heads or a thunderbolt with three flashes of lightning in her right hand. The female rider is thus clearly a warrioress charging at the enemy. Similar types appear on other coins of the Redones, dated to the 2nd c. BC, where the naked female warrioress rides a charger with no saddle, holds a shield in her right hand and vertically brandishes the hilt of a knife or sword in her left hand (fig. 15).1453Under the horse appears a lyre.

A golden coin from the area of Amiens (Somme), in the territory of the Ambiani, probably dating from the 2nd c. BC, also has a naked female rider on the reverse (fig. 16).1454The woman rides two horses and is turned towards the onlooker. Her hair is done in two tousled buns on each side of her head and she wears a belt and a shoulder-cover. She holds a shield in her left hand and a huge torque* in her right hand. A long palm is represented flying over the shield. She does not have any offensive weapons and is not represented charging at the enemy: she rather seems to march past or parade. The shield is a symbol of war, while the palm is a symbol of glorification. As for the torque*, it is indicative of the divine nature of the rider or it accounts for the spoils of war she has brought from the battlefield. Jewels and weapons were indeed collected from the dead enemies at the end of a battle, because it was a symbol of the fighter’s valour.1455 They were generally taken and deposited in the sanctuary of the martial deity to thank him for his support and to honour his potency. As Brunaux explains, each warrior despoiled his victims of his possessions and usually brought them back to the city, proudly and solemnly marching past to the sound of songs of triumph.1456 This female rider must be an illustration of such a tradition. She appears indeed as the representation of a triumphant and glorified warrioress, coming back from the battlefield and showing her spoils of war.

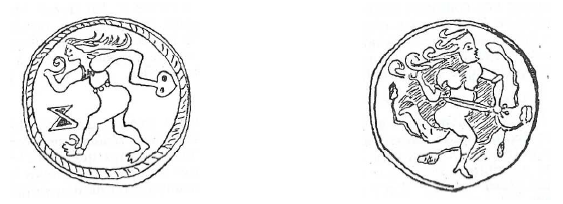

Finally, two golden coins from Ancenis (Loire-Atlantique) and Falaise (Calvados) have the figurations of running naked women holding offensive weapons in their hands. The coin from Ancenis, dated to the 3rd c. BC, has the representation of a naked woman with long hair walking fast and holding a sort of sickle in her right hand and an undetermined object in the other (fig. 17).1457 The second coin, dated to the 3rd c. BC, depicts a woman with long curly hair streaming in the air. The character is frantically racing and holds a two-edged sword in her left hand (fig. 17).1458 According to De Vries, they are the portrayal of women at war or martial goddesses.1459

The nudity of those war-like women can be explained by the fact that Celtic warriors were often seen entering the fray all naked with only weapons in their hands.1460This idea is attested by some iconographical devices1461 and Classical accounts. In The Library of History, Diodorus Siculus describes the helmets and weapons of the Celtic warriors and indicates they went into battle naked:

‘Some of them have iron cuirasses, chain-wrought, but others are satisfied with the armour which Nature has given them and go into battle naked. In place of the short sword they carry long broad-swords which are hung on chains of iron or bronze and are worn along the right flank. And some of them gather up their shirts with belts plated with gold or silver.1462 ’Similarly, Polybius (203-120 BC), in a passage of The Rise of the Roman Empire, which tells of the battle of Telamon in 225 BC opposing the Romans to an alliance of Gauls (Insubres, Boii, Taurisci and Gaesatae), recounts that the Gaesatae combatted naked. This is the reason why they were defeated by the Roman javelin-throwers:

‘[…]For their part the Romans felt encouraged at having trapped the enemy between their two armies, but at the samee time dismayed by the splendid array of the Celtic host and the ear-splitting din which they created. There were countless horns and trumpets being blown simultaneously in their ranks, and as the whole army was also shouting its war-cries, there arose such as babel of sound that it seemed to come not only from the trumpets of the soldiers bt from the whole surrounding countryside at once. Besides this the aspect and the movements of the naked warriors in the front ranks made a terrifying spectacle. They were all men of splendid physique and in the prime of life, and those in the leading companies were richly adorned with gold necklaces and bracelets. The mere sight of them was enough to arouse fear among the Romans, but at the same time the prospect of gaining so much plunder made them twice as eager to fight.However, when the Roman javelin-throwers, following their regular tactics in Roman warfare, advanced in front of the legions and began to hurl their weapons thick and fast, the cloaks and trousers of the Celts in the rear ranks gave some effective protection, but for the naked warriors in front the situation was very different. They had not foreseen this tactic and found themselves in a difficult and helpless situation. The shield used by the Gauls does not cover the whole body, andd so the tall stature of these naked troops made the missiles all the more likely to find their mark. […] In this way the martial ardour of the Gaesatae was broken by an attack with the javelin.1463 ’

By comparison with Polybius’ account, the various coins referred to above give the representations of two running female warrioresses holding weapons, a female charioteer and three different riders charging at the enemy and brandishing weapons: shields, spears, hilts of knife or sword. Those are clearly representations of warrioresses taking part in combat. The last figuration is that of a warrioress coming back from the battlefield, showing her spoils of war and glorified for her deeds. The female riders are not representations of the goddess Epona, who is portrayed riding a horse peacefully and is never associated with war aspects. Are those woman riders at full gallop representations of human or divine warrioresses? To answer that question it is first necessary to determine whether the Classical texts tell of Celtic women taking up arms and fighting side by side with men. While Irish mythology offers colourful descriptions of war-goddesses, data concerning possible Gallo-British divine warrioresses are near inexistent and sparse. As we have seen, Irish mythology does not tell of armed divine female riders taking part in battle, but of horrifying unarmed fighting ladies who take the shape of a crow, terrorize their foes and falter their courage by their appearance, shrieks and incantations, so could those female riders then be the figurations of Gaulish war-goddesses? The etymological, epigraphic and iconographical facts evidencing such a cult must therefore be analyzed.