b) The ‘Fortress’ Goddessses: Dunisia and Ratis

The goddess name Dunisia is known from a single inscription, discovered in 1879, when the church of Bussy-Albieu, situated near Montbrison (Loire), in the territory of the Segusavi, was demolished.1475 The dedication, dating from the 1st c. AD, is very damaged, incomplete and remains somewhat obscure. The inscription associates Dunisia with the goddess Segeta, who is mentioned in two other dedications from Feurs (Loire) and Sceaux-en-Gâtinais (Loiret): (f)il(ius) A. (ci)vitat(is) (Segusiavi?) (pr)aefecto tem(puli?) deae Segetae Fo(ri) allecto aquae (te)mpuli Dunisiae (pr)aefectorio ma(ximo) ejusdem tem(puli) pag(us)…blocnus.1476

Decipherment of this dedication remains problematic and complex. It mentions a temple erected to the goddess Segeta and another one to the goddess Dunisia. The dedicator, who is anonymous, is apparently endowed with municipal honour or priesthood and seems to have been admitted in a corporation attached to temple duties (praefectus).1477 The name Fori, which follows the name of the goddess, must refer to Feurs, a village situated 16 kilometres from Bussy-Albieu, where another inscription to Segeta engraved on a weight was found in 1525.

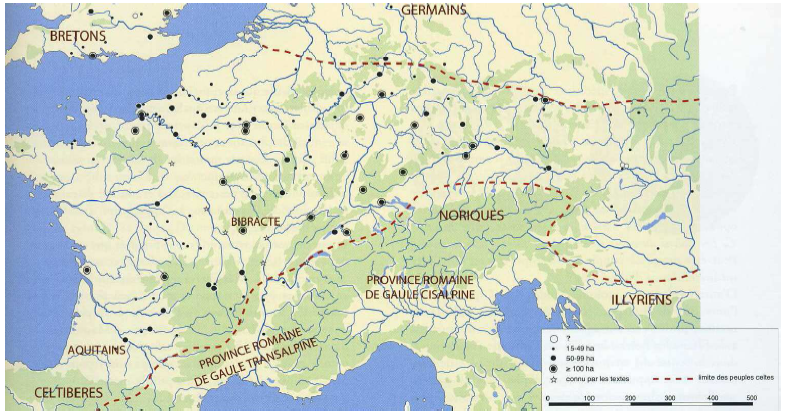

Dunisia’s name is related to the divine epithet Dunatis, given to Mars Bolvinnus in Bouhy (Nièvre, territory of the Senones)1478 and to Mars Segomo in Culoz (Ain, territory of the Ambarri).1479 Dunisia and Dunatis are both derived from the Celtic word dūnon meaning ‘hill’, ‘enclosed area’, ‘fortified town’, ‘citadel’, cognate with Old Irish dún, ‘fort, fortress’, Welsh dinas, ‘city’ and Breton din, ‘fortified town’.1480 This form, corresponding to Latin dunum, is attested by a quantity of place names in Europe, such as Lugdunum, ‘the Fort of Lugus’ (Lyons, Rhônes-Alpes), Eburodunum, ‘the Yew-Fort’ (Embrun, Hautes-Alpes), etc. These fortified cities, referred to as oppidum* in the singular form and oppida* in the plural form, developed from the beginning of the 2nd c. BC until the end of the 1st c. BC, the most important phase being the last quarter of the 2nd c. BC.1481 The phenomenon of hill-top fortified towns goes back to very ancient times. The first occurrences appeared in the 5th millennium (Ancient Neolithic) and they were particularly developed at the end of the Bronze Age (c. 900 BC) and in the first period of the Iron Age when insecurity increased, but those are smaller and somewhat different from the oppida*.1482 The oppidum* covered an area between 30 to 1,500 hectares, and was generally enclosed by ramparts and closed by ‘pincer’ doors named ‘Zangentore’.1483 They were usually situated on hills or mountains, which allowed them to dominate the surroundings and to protect themselves from the foes. Excavations carried out in the second half of the 19th c. revealed the presence of such fortified cities in a large part of Europe, Britain and Ireland (fig. 19). On account of their name, it is undeniable that Mars Dunatis and Dunisia are the embodiment of the dunum, i.e. ‘the agglomeration protected by an enclosure’ or ‘the fortified town’.1484 The fort being a place of refuge for the rural population in period of war and the centre of living, sometimes for the population of a whole territory, Dunatis (‘the Fort’) and Dunisia (‘the Fortress’) may be understood as the deities embodying and presiding over the stronghold, protecting their people and city.

This function of protectress of the fortress may be echoed in another goddess name: Ratis. She is venerated in two British inscriptions from Birdoswald (Cumbria): Deae Rati votum in perpetuo, ‘To the goddess Ratis a vow in perpetuity’,1485 and from Chesters (Cheshire): Dea(e) Rat(i) v.s.l.,‘To the goddess Ratis (someone) willingly fulfilled his vow’ (fig. 20).1486 Olmsted mistakenly relates her name to the god name Ratomatos, which he derives from a Celtic root rato-, meaning ‘grace’, ‘fortune’.1487 This god name, which is listed neither in Jüfer’s Répertoire des Dieux Gaulois nor in Delamarre’s Noms de personnes celtiques dans l’épigraphie celtique, actually does not exist. Ellis Evans specifies that this divine name mentioned by Holder is a misreading of CIL XIII, 2583 found in Mâcon: […] Diorata Mato Antullus Mutilus (….).1488 As for the goddess name Ratis, it is not based on Celtic rato-, ‘fortune’, ‘grace’. It can be related either to Celtic rate, ratis, signifying ‘wall’, ‘rampart’ and by metonymy ‘fort’ – cf. Old Irish ráith, ‘lump of earth’, ‘fort’ - or to ratis, ‘fern’, but, according to Delamarre, this latter etymology* is far less probable.1489 The goddess Ratis must therefore signify ‘the Fortress’ and possess the same functions as Dunisia. Anwyl and Olmsted suggest that her name is similar to Ratae, the ancient name of Leicester (Leicestershire), and that she must have been the eponymous goddess of the city.1490 This theory is, however, difficult to believe insomuch as the two inscriptions were not discovered in the area.