c) Protection of the City

Bibracte

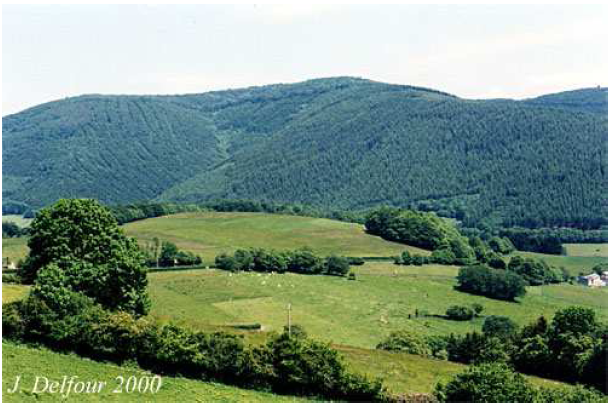

While Dunisia and Ratis are the personifications and protectresses of Celtic fortified cities in general, some other goddesses are embodiments and guardians of particular oppida* and cities. Such is the case of the goddess Bibracte, the eponymous goddess of the chief city of the Aedui, mentioned by Caesar in De Bello Gallico and by Strabo in his Geography.1491 In the middle of the 19th c., the emplacement of this important Gaulish oppidum* was a controversial issue and brought into vehement conflict the scholars of the time. C. Rossigneux maintained that Bibracte was Augustodunum (Autun), while Jacques-Gabriel Bulliot claimed it was located on Mont-Bevray (Saône-et-Loire) (fig. 21).1492 The excavations carried out by Bulliot and Joseph Déchelette on this site from 1867 to 1907, resumed between 1984 and 1995, revealed the traces of an ancient occupation and definitely settled the question over the location of Bibracte.1493 These archaeological discoveries showed that settlement on Mont-Beuvray went back to the Neolithic Period. It also evidenced the presence of the Aedui from the end of the 2nd c. BC to the end of the 1st c. BC, when, becoming allied with the Romans, they left their ancient hill fort to settle twenty kilometres away in the new city of Augustodunum (Autun).1494 The oppidum* of Bibracte, which gave its name to Mont-Beuvray, covered an area of 200 hectares and was fortified by a double rampart enclosing a complex inside organisation, with aristocratic residences, a gigantic astronomically oriented basin, a market, arts and crafts districts and sanctuaries located in the highest part of the plateau.1495

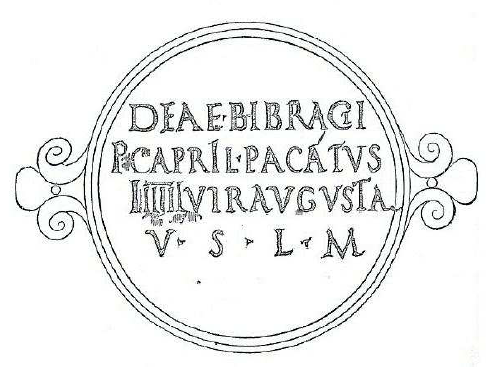

Three late inscriptions, probably dating from the 4th c. AD, discovered in Autun (Saône-et-Loire), are dedicated to the goddess Bibracte. The first inscription, discovered in 1679 in an ancient well, is engraved on a circular medallion in silver-plated brass, the authenticity of which was challenged by some specialists, who considered it to be the work of a forger.1496 Those doubts, arising due to the argument over the emplacement of the Aedui hill fort, have apparently been settled. The inscription reads: Deae Bibracti P. Capril(ius) Pacatus IIIIIIvir Augustal(is) v(otum) s(olvit) l(ibens) m(erito), ‘To the Goddess Bibracte, Publius Caprilius Pacatus, augustal sevir, paid his vow willingly and deservedly’ (fig. 22).1497 The dedicator bears the tria nomina of Roman citizens and is an augustal sevir, i.e. a freed slave designated for the year to supervise the Imperial cult of the city. Two other fragments of inscriptions mentioning the goddess were discovered in Autun but are now lost.1498 The first one read Bibracti (as)signatum, ‘attributed to Bibracte’, while the other one was engraved on the socle of a statue, the two feet of which only remained: Deae Bibracti, ‘To the Goddess Bibracte’.

The etymology* of Bribracte remains controversial today. On the one hand, most scholars admit that Bibracte is to be related to Celtic bebros, bebrus signifying ‘beaver’ - cf. Latin beber.1499 It is worth noting that some Celtic peoples bear that name, such as the tribe of the Bibroci, situated in the south of Britain (Berkshire, west of modern London), and the Pyrenean tribe of the Bebruces, who had for King Bebrux ‘Beaver’. The Mont-Beuvray or Bibracte can be thus glossed as ‘the Beaver-Mount’, which may indicate that the hill was inhabited by beavers in ancient times, but this remains to be proved. On the other hand, other specialists, such as Olmsted or Lacroix, side with Vendryes, who analyzes Bibracte as bi-bracto-, a reduplicated form of the past participle bract-, similar to Greek phráktos, phrássō, ‘fortified’ or ‘to fence, to wall something in’, and suggests that Bibracte might mean ‘The Very Fortified (Mount)’.1500 This etymology* is enticing, for Bibracte is actually a fortified mount, the ramparts of which may be of very ancient date, predating the Aedui.1501 Nevertheless, it remains dubious for most specialists of the Gaulish language.

Finally, some have tried to relate her name to the Latin root biber signifying ‘drink’, to justify her divine attachment to the numerous springs and rivers of Mont-Bevray. From this, Vendryes infers that Bibracte was originally a personification of the springs, which are numerous on the site of the oppidum*, and Bulliot adds that she must have had the functions of a healer like Sequana.1502 Yet, as Christian Goudineau rightly points out, Bibracte is certainly more a deification of the mount than the springs, for it is the mount which stands out in the landscape of the Morvan and must have originally been worshipped.1503 The cult may nonetheless have later extended to the springs of Mont-Beuvray. Excavations carried out at the Fontaine Saint-Pierre, dated 1st c. BC, revealed much archaeological material, attesting to a healing cult. An ear in bronze echoes the anatomic ex-votos* unearthed at the Sources of the Seine, but this does not prove that Bibracte was specifically viewed as a healing goddess.1504 At the summit of Mont-Beuvray, not very far away from this spring, was unearthed what Goudineau defines as “a proto-historic religious enclosure” surrounded by a ditch, where two vases dating from the end of the 1st c. BC were found. 1505 According to him, this enclosure could be interpreted as a place of devotion for the goddess Bibracte, but this theory remains speculative.

Bibracte must originally have been the deification of the sacred mount and must have represented its highness and force. When the powerful sept* of the Aedui chose to settle and build their fortress on the plateau of Mont-Beuvray, her name was given to the fortified city and she became its representative and patroness, bringing well-being and protection to her people.