2) Martial attributes: Strength, Courage and War Fury

Other goddesses may pertain to combat and war, for their names imply feelings of rage and fury and denote war-like qualities, such as force, bravery and valour.

a) Belisama (‘the Most Powerful’?)

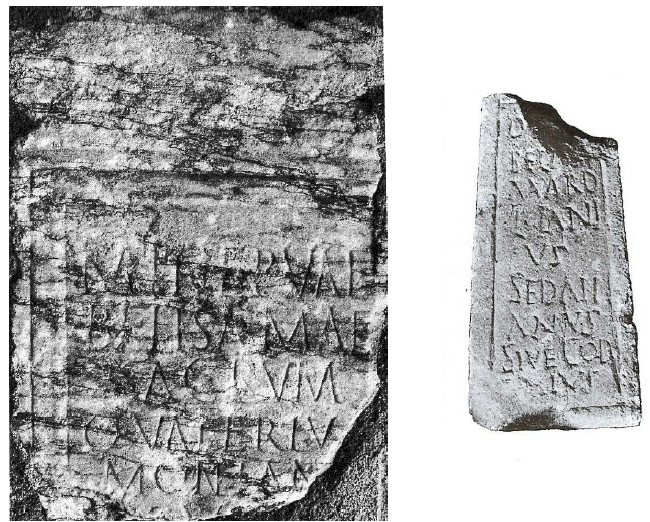

Belisama is known from two inscriptions of completely different origin, which indicates that she is not a topical* goddess presiding over a specific area or sept*. The first dedication is engraved on an altar in white marble with blue-grey veins, discovered in re-employment* in the bridge of Saint-Lizier (Ariège), which was the main oppidum* of the Consoranni tribe. The inscription associates her with the Roman goddess Minerva: Minervae Belisamae sacrum Q(uintus) Valeriu[s] Montan[us e]x v(oto) [s(uscepto)], ‘Sacred to Minerva Belisama, Quintus Valerius Montanus (offered this monument) in accomplishment of his vow’ (fig. 32).1540 Contrary to what Raymond Lizop maintains, there is no archaeological evidence testifying to a sanctuary to Belisama in the upper part of the town.1541

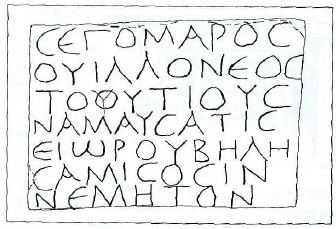

Belisama is not a mere epithet given to Minerva, since she is venerated on her own in another dedication, discovered in 1840 in Vaison-la-Romaine (Vaucluse), the chief city of the Vocontii tribe.1542 The inscription is of great interest, for it dates from around the 2nd or 1st c. BC and is in the Gaulish language and Greek lettering: σεγομαρος / ουιλλονεος / τοουτιους / ναμαυσατις / ειωρου βηλη- / σαμι σοσιν / νεμητον, ‘Segomaros son of Villū, citizen of Nîmes, offered this sacred enclosure to Belesama’ (fig. 33).1543 The name of the dedicator, Segomaros (‘Great Strength’ or ‘Great by his Victories’), and the name of his father, Villoneos, the meaning of which is unknown, are Celtic.1544 Segomaros offers the goddess a nemeton, that is a ‘sacred enclosure’, ‘sacred grove’ or ‘sanctuary’.1545 The nemeton was a sacred place of cult and veneration reserved to a deity, where human beings, apart from the initiates, were not allowed. Generally of quadrangular form, dotted with trees and a hollow altar in its centre, its limits were marked out on the ground by a ditch and sometimes enclosed by a fence.1546 Segomaros, a peregrine* bearing a typical Celtic name, coming from the city of Nîmes, had thus a sanctuary erected in honour of a Celtic goddess in the 2nd or 1st c. BC, which shows the importance of Belisama’s worship and the attachment of the indigenous people to their beliefs and cults.

Belisama undoubtedly bears a Celtic name, the significance of which remains much debated. On the one hand, it can be related to an IE theme *bhel-, which is usually translated ‘white’ or ‘brilliant’ but actually denotes ‘force’.1547 Delamarre explains that the fanciful and inaccurate interpretation of *bhel- as ‘brilliant’ comes from the fact that the Gaulish god Belenus/Belinus, who is known from fifty-one dedications coming from southern and central Gaul and Aquileia (North Italy), is equated with the Roman solar god Apollo in nine of the inscriptions.1548 In fact, his association with Apollo is certainly not due to a solar imagery but to common healing functions. It is indeed clear that Belenus is a curative god, for he is attached to various water sanctuaries, such as the sacred medicinal springs at Sainte-Sabine (Côte d’Or).1549 Belenus / Belinus is to be understood as ‘the Master of Power’ or ‘the Powerful One’ rather than ‘the Bright One’. Belisama being its superlative form, her name thus means ‘the Very or Most Powerful One’ and not ‘the Most Brilliant’ as many scholars maintain.1550

On the other hand, Lambert specifies that her name may be derived from the verbal theme *gwel- signifying ‘to pierce’, ‘to kill’.1551 It appears thus that the two suggested etymologies refer to the notion of power, strength and killing. Belisama might thus be envisaged as a goddess related to war and combat. This idea is highly likely, since Belisama is associated with Minerva in the dedication from Saint-Lizier, and, as is well-known, Minerva has pronounced war-like functions among others.1552 As the two inscriptions were discovered at the location of the ancient chief fortified cities of the Consorani and the Vocontii, her powers may have been invoked to protect the place and the inhabitants in time of trouble.

The irrelevant etymology* of Belisama as ‘Most Brilliant’ has given rise to inappropriate theories concerning her functions. Some scholars suggest that Belisama could symbolize lightning or the fire of the forge of Vulcan and be connected to Irish Brigit, who is the patroness of smithcraft and is often assigned fire and shining aspects - these attributes actually characterize more the Saint than the goddess.1553 As for Lacroix, he proposes to compare Belisima’s name to the Greek proper name Hellène meaning ‘Mistress of Light’. According to him, Belisama could personify the rising sun and be a goddess of the dawn or spring.1554

De Bernardo Stempel and Delamarre notice that Belisama may be etymologically related to the goddess Belestis (*Bel-isto = Bel-isamo?),1555 honoured in St. Leonhard (Austria): Belesti Aug(ustae) T(itus) Tapponius Macrinus et Iulia Sex(ti) l(iberta) Cara cum suis vslm, and Unterloibl: Belesti Aug(ustae) sac(rum) Latinus Tapponi Macrini ser(vus) vslm.1556 De Bernardo Stempel may however be mistaken when she translates Belestis as ‘the Most Brilliant’ and assumes that she is a Moon goddess, as Sirona is a Star goddess.

Other specialists regard Belisama as a water-goddess because Ptolemy gave her name to the River Ribble in north-west England (Lancashire).1557 Another river, Le Blima, a small tributary of the Dadou in Tarn (France), might be derived from her name too.1558 As there is no archaeological material evidencing a water cult attached to Belisama – the inscriptions were not found in or near water sanctuaries, ex-votos proving a healing cult were not discovered either – those names of rivers do not produce proof of such a function. The fact that the god Belenus is often associated with healing water sanctuaries does not support that idea either, since Belisama’s name is not the feminine version of Belenos but of Belisamarus. This god is mentioned in an inscription engraved on a prismatic altar discovered in Châlon-sur-Saône (Saône-et-Loire), in the territory of the Aedui. The dedication is the following: De[o] Beli[s]amaro L(ucius) Lanius Sedatianus sive Cod[on]ius, ‘To the god Belisamarus, Lucius Lanius Sedatianus or Codonius’ (fig. 32).1559 The dedicator bears the tria nomina of Roman citizens. His nomen*, cognomen* and ‘nickname’ (Codonius) are Latin.1560