A) The deposition of votive offerings in watery places

A certain number of studies have demonstrated that the deposition of artefacts in ‘wet places’ - sites linked to water - was a particularly widespread custom in the Bronze and Iron Ages.1656 Aidan O’Sullivan, speaking of Ireland and Britain, explains that ages can be differentiated with regard to the evolution of the practice.1657 In the Middle Bronze Age, it was mainly weapons and tools, such as dirks, rapiers and axes, which were deposited in rivers. From the Late Bronze Age, the ritual phenomenon developed considerably: hoards of weapons, tools, personal ornaments and musical instruments were placed in watery places. In the Iron Age, the deposition of swords, spearheads, spear-butts, jewels, bronze cauldron and horse trappings predominated.

What emerges from the comprehensive analysis of Richard Bradley in the Passage of Arms is that the deposition of weaponry and personal ornaments in rivers, lakes and bogs is not meaningless and insignificant.1658 The large number of artefacts constently deposited in specific areas of rivers, lakes and bogs, from the Bronze Age onwards, throughout Ireland, Britain and Gaul, shows that those items were not accidentally dropped or lost. Bradley draws the conclusion that those deposits were votive offerings, which were part of religious rites fulfilled in honour of deities inhabiting the waters; a theory with which O’Sullivan, Eogan, Herity, Green among others have concurred.1659 This is all the more probable as many of the metal materials had been previously damaged or destroyed before being deposited. Destroying the weapons before offering them to the gods is a practice known from Prehistoric and especially Celtic times.1660 The war sanctuary of Gournay-sur-Aronde (Somme) is a good example of this ‘rite of passage’ aiming at honouring the gods by offering them unusable weapons.1661

Examples of such deposits of offerings in lakes, bogs and rivers are multiple. In 1942, a hoard of 150 objects, dated 2nd c. BC to 1st c. AD, consisting of weapons, shields, tools, cauldrons and chariot-fittings, was dredged from Llyn Cerrig Bach, a small lake situated in the north-west of the island of Anglesey (Wales).1662 In Scotland, no less than fifty-three Late Bronze Age weapons were recovered from Duddingston Loch in 1778.1663 In Ireland, collections of metal materials, dating from the Late Bronze Age, were found in Lough Érne (Co. Fermanagh), Lough Gur (Co. Limerick) and Mooghaun Lough (Co. Clare).1664 Similarly, on the Continent, a large assemblage of weaponry, jewellery, tools and perishable organic materials, dating from the 3rd c. BC onwards, was retrieved from Lake Neuchâtel in Switzerland.1665 In Duchcov (Czech Republic), a huge 4th-century BC bronze cauldron containing about 2,500 La Tène jewels was discovered in a thermal spring called Obří pramen, ‘The Giant’s Spring’.1666 The archaeological discoveries of hoards in lakes are evidence in support of the accounts of the Greek geographer Strabo and the Roman historian Justinus, who relate that the Volcae Tectosages had flung a huge treasure composed of silver and gold into the Lake of Toulouse to appease the gods’ wrath.1667 It is said that the Roman consul Quintus Servilius Caepio, who seized and plundered the city in 106 AD and fished up the gold in the sacred lake, was doomed to a tragic end. In The Geography, Strabo recounts the testimony of the Greek philosopher Poseidonius:

‘ And it is further said that the Tectosages shared in the expedition to Delphi; and even the treasures that were found among them in the city of Tolosa by Caepio, a general of the Romans, were, it is said, a part of the valuables that were taken from Delphi, although the people, in trying to consecrate them and propitiate the god, added thereto out of their personal properties, and it was on account of having laid hands on them that Caepio ended his life in misfortunes — for he was cast out by his native land as a temple-robber, and he left behind as his heirs female children only, who, as it turned out, became prostitutes, as Timagenes has said, and therefore perished in disgrace. However, the account of Poseidonius is more plausible: for he says that the treasure that was found in Tolosa amounted to about fifteen thousand talents (part of it in sacred lakes), unwrought, that is, merely gold and silver bullion [...] But, as has been said both by Poseidonius and several others, since the country was rich in gold, and also belonged to people who were god-fearing and not extravagant in their ways of living, it came to have treasures in many places in Celtica; but it was the lakes, most of all, that afforded the treasures their inviolability, into which the people let down heavy masses of silver or even of gold.1668 ’As for Justin, he relates the same story about the treasure deposited in the Lake of Toulouse:

‘The Tectosagi, on returning to their old settlements about Toulouse, were seized with a pestilential distemper, and did not recover from it, until, being warned by the admonitions of their soothsayers, they threw the gold and silver, which they had got in war and sacrilege, into the lake of Toulouse; all which treasure, a hundred and ten thousand pounds of silver, and fifteen hundred thousand pounds of gold, Caepio, the Roman consul, a long time after, carried away with him. But this sacrilegious act subsequently proved a cause of rain to Caepio and his army. The rising of the Cimbrian war, too, seemed to pursue the Romans as if to avenge the removal of that devoted treasure.1669 ’The authenticity or otherwise of this story and the actual nature of the gold of Toulouse is not the point here.1670 The interesting thing is that this account evidences the sacred quality of lakes and exemplifies the tradition of depositing hoards and treasures in water to propitiate the gods.

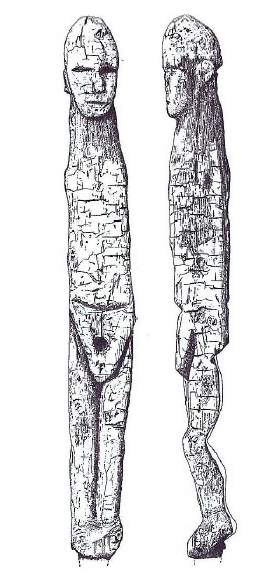

In Ireland, many discoveries of this type have been made in bogs. In the course of the 18th and 19th c., at least sixty-three types of swords, spearheads, gold bowls and gold dress-fasteners, dated 900-600 BC, were discovered in the Bog of Cullen (Co. Tipperary).1671 From the Bog of Dowris (Co. Offaly), an impressive 7th-century BC hoard of swords, chapes, spearheads, socketed axeheads, knives and gouges, razors, buckets, cauldrons and horns, was dredged (fig. 1).1672 As for the bog site at Lisnacrogher (Co. Antrim), it revealed an important range of personal ornaments and weapons.1673 Finds of great interest are the Bronze and Iron Age anthropomorphic* wooden figures, possibly representing a deity, respectively dug up at the Bog of Ralaghan (Co. Cavan) (fig. 2),1674 in Lagore Lake (Co. Meath)1675 and on trackways in Cloncreen Bog at Ballykilleen1676, at Kilberg (Co. Offaly)1677 and at Corlea (Co. Longford).1678

The deposition of votive offerings is attested in rivers too. Archaeological discoveries have shown that hoards were generally dropped at specific areas, such as fords. The only difference between river and lake/bog deposits is, as O’Sullivan explains, that “weaponry is dominant in rivers, while ceremonial items (cauldron, horns, gold) tend to be mostly found in bogs”.1679 In Gaul, a significant number of Late Bronze Age swords were discovered in the River Loire,1680 and numerous 2nd-Iron Age spearheads and swords were recovered from the River Saône, more specifically at fords.1681 From the River Thames in Britain, spearheads, swords, pieces of armour and defensive weapons have been dredged since the 19th c. These include the two Wandsworth shield bosses, dating to the 3rd c.-1st c. BC, the 1st-century BC horned helmet (chapter 3, fig. 24) and the bronze shield inlaid with enamel, dated to the beginning of the 1stc. AD (fig. 3).1682 Similarly, in Ireland, swords, dirks and rapiers, dating from the Bronze and Iron Ages, were found in the beds of the River Shannon, the River Bann, the River Barrow and the River Érne at particular places.1683

The deposition of votive offerings in water in Gallo-Roman and Romano-British times is particularly attested at the sources of rivers, thermal springs and fountains. Such offerings to the gods, generally known as ex-votos for this period, are of different types. They can be in wood, stone, bronze, gold, iron or in sheet metal1684 and may consist of representations of the pilgrims themselves, swaddled babies and protective deities. For instance, Venus Anadyomene* or Mother Goddesses; personal ornaments such as fibulas*, brooches, rings, bracelets and hairpins; coins; potteries; epigraphic altars and anatomic ex-votos* i.e. images of painful or deceased body parts, such as legs, breasts, eyes, arms, heads, feet and internal organs.1685 Such ex-votos have been discovered in great quantity at the Sources-de-la-Seine (Côte d’Or), Chamalières (Puy-de-Dôme), Bourbonnes-les-Bains (Haute-Marne), Luxeuil-les-Bains (Haute-Saône) in France and at Bath (Somerset, GB), etc. Healing springs were generally in the hands of a specific deity, whose name could be identified when dedications were discovered on the site. The Sources-de-la-Seine was presided over by the goddess Sequana, Bath by Sulis, Luxeuil by Brixta and Luxovius, while the ‘Source des Roches’ in Chamalières - where numerous coins, potteries and thousands of ex-votos in wood testifying to a curative cult were unearthed - was apparently under the patronage of the god Maponos, invoked in a magical text in the Gallo-Latin language.1686

In Gallo-Roman times, archaeology thus evidences how sites linked to water were worshipped. Pilgrims came to springs to have their pains soothed and prayed to the deity inhabiting the healing waters. It is interesting to note that the religious rites would have involved two stages. Sick pilgrims must have first come to the site to invoke and ‘sign a contract’ with the deity. A gift was generally made to the deity with the aim of earning its benevolence. The anatomic ex-votos* were probably deposited on the first visit to the shrine. In leaving a representation of the deceased body part in the hand of the deity, the pilgrim was thought to journey back without pain or illness. Such votive offerings can be called ‘ex-dono’.1687 They are different in nature from ex-votos, insomuch as ex-votos were offered once the vow had been fulfilled. To thank the deity, pilgrims would go back to the place of devotion and offer another gift to the deity: a jewel, coins, a vase or a dedication ending with the abbreviated votive formula VSLM, i.e. v(otum) s(olvit) l(ibens) m(erito), i.e. ‘(the dedicator) paid his or her vow willingly and deservedly’.1688 This phrase indicates that the vow had been granted and expresses the sincere gratitude of the dedicator. Votive offerings were thus either propitiatory or testimonies of gratitude, though it is not always possible to determine whether the offering was made before or after receiving divine grace. What is clear, however, is that in Gallo-Roman and Romano-British times, springs, rivers and fountains were believed to be the dwellings of gods and goddesses, who personified the water and exercised their curative and salutary virtues over the people.

People deliberately cast metalwork into water as a gift to the supernatural powers, probably to earn their benevolence and gratitude. This would mean that waters were believed to be personified and inhabited by divine entities, and this idea is confirmed by the meaning of certain hydronyms*, which directly refer to the preternatural character of the river or spring.