B) Numinous rivers or springs: deva, divonna, banna

Alfred Dauzat explains that most ancient river names are mere ‘generic names’ describing the appearance, nature and quality of the river, such as the ‘slow water’, the ‘black, green, white or red water’, the ‘slow or fast-flowing water’, or of the surroundings through which it flows, such as the ‘water of the woods’, ‘stream of the mount’, ‘torrent of the cliff’, etc.1689 In Gaul, the name of the River Doubs, which rises in Mouthe (Doubs) and joins the River Saône at Verdun-sur-le-Doubs (Saône-et-Loire), was anciently called Dubis (‘the Black (Water)’), derived from a Celtic word dubnos meaning ‘deep, black’.1690 The River Thève, which flows through Seine-et-Marne, Oise and Val d’Oise, originally bore a Celtic name Tava signifying ‘the Tranquil or Quite One’, from a Celtic root tavo- < tauso-, ‘tranquil, quite’.1691 As for the Glanis, a non-identified river flowing in the Ardennes, it is derived from a Celtic root glano- meaning ‘pure, bright’.1692 In Ireland, the name of the two rivers an Abhainn Mhór in Ulster (erroneously anglicized as the Blackriver and the Blackwater) signifies ‘Great River’, while the name of the river an Abhainn Dubh in Co. Cavan (Ulster) means ‘Black River’, and the name of the river an Uinsinn (the Unshin) in Connacht meant ‘the River of the Ash Tree’.1693 These names are thus descriptive and involve no particular religious tradition.

Other river names, based on deva and divona, are numinous names clearly reminiscent of the sanctity and divinisation of rivers in ancient times. They are derived from an old IE root *deivo, *deiva, ‘divine’, which gave the forms devos in Gaulish, dia in Old Irish, duy in Old Cornish and duiu, duw, dwy in Welsh.1694 The word divona is a derived form of deva and must have originally designated a ‘sacred spring’.1695

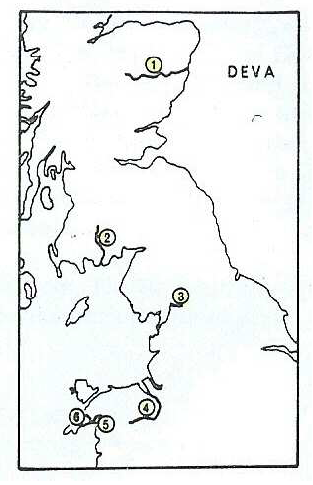

Many river names in Britain, Scotland, Wales, Ireland, Gaul, Belgium and Spain stem from the ancient form deva, ‘divine’, ‘goddess’. Such is the case of the Irish River Dee, which flows into the Irish Sea, north of Annagassan (Co. Louth); of the British River Dee, which flows into the Irish Sea in Cheshire (fig. 4: n° 3); and of the Welsh rivers Afon Dwyfawr (‘Big Dee’) and Afon Dwyfach (‘Small Dee’) which unite below the village of Llan Ystumdwy in the Lleyn Peninsula (Gwynedd) (fig. 4: n°4, 5 and 6). In Scotland, two rivers Dee are recorded: the one which flows into the Irish Sea in Kirkcudbright (Dumfries and Galloway) and the one which joins the North Sea at Aberdeen (Aberdeenshire) (fig. 4: n°1 and 2).1696 In Gaul, there is important evidence of ‘deva’ rivers: La Dieue, a tributary of the River Meuse in Dieue (Meuse); La Dive, a tributary of the River Thouet in Saint-Just-sur-Dive (Maine et Loire); La Dive, a tributary of the River Vienne in Salles-en-Toulon (Vienne); La Dive, a tributary of the River Bouleur in Voulon (Vienne); La Dive, a tributary of the River Orne in Peray (Sarthe); La Dives, which flows into the English Channel in Dives-sur-Mer (Calvados); La Dives, a tributary of the River Oise (Oise); La Die, a tributary of the River Drac (Isère); La Divatte, a tributary of the River Loire in La Varenne (Maine et Loire); La Divette, a tributary of the River Dives in Cabourg (Calvados); La Divette, which flows into the English Channel at Cherbourg (Manche); La Diosaz, a tributary of the River Arve in Servoz (Haute-Savoie), etc.1697 In the North West of Spain, two coastal rivers, called la Deba - situated to the west of Saint-Sebastian - and la Deva - flowing west of Santander - are also ‘divine’ rivers.1698 In Belgium, there are also occurrences of the name, such as the River Dievenbeke in Ingelmunster, the ancient River Dieve in Rotselaar (now the name of a fief) and the River Dieversdelle in Uccle-lez-Bruxelles (today’s Diesdelle).1699

Other river- or spring-names are derived from an ancient divona, ‘divine (spring)’.1700 In Britain, the River Devon, a tributary of the River Trent (Nottinghamshire), and in France, the brook Devon which flows in Mayenne, are reminiscent of such an appellation. Springs sometimes transmitted their name to the cities where they were located. For instance, the town of Cahors (Lot) was called Doueona in the 2nd c. by Ptolemy and Divona in the 4th c. on the Table de Peutinger.1701 This name originally designated the famous Gallo-Roman ‘Fontaine des Chartreux’ in Cahors, situated at the entrance of the capital city of the Cadurci.1702Similarly, Divonne-les-Bains (Ain) got its name from the spring Divonne, famous for its curative virtues, which gushes forth in the city.

Divonna is not attested as a goddess by votive inscriptions. Nonetheless, an obscure text of magical character, dating to the 3rd or 4th c. AD, engraved on the face A of a lead plaque and found in 1887 in a well of a Gallo-Roman villa in Rom (Deux-Sèvres), might be addressed to the goddess.1703 It was found together with fifteen other anepigraphic lead plaques. The origin and meaning of this text remains contested and obscure, because of the uncertainty of the language (Gaulish? Latin? Greek? Pictish?), the identification of the letters and the segmentation of the text. Lambert, in La langue gauloise and RIG II, sums up the various erroneous, fanciful and imaginary readings, transcriptions and translations which have been proposed.1704 The text given hereafter is from RIG II; but no relevant translation has been proposed yet:

‘apecialligartiestiheiontcaticato (or caticno?)

atademtissiebotu

cnasedemtiticato (or titicno?)

bicartaontdibo

nasociodecipia

sosio pura sosio

eoẹ….eiotet

sosiopurah…..

suade…ix.o.cn

auntaontiodiseịạ’

According to Lambert, the theories of Egger Rudolf and Otto Haas, who believe it to be a defixio* written against enemies, are unconvincing.1705 Edward Nicholson claims the text is in Pictish and suggests it is a litany addressed to a spring-goddess to prevent her from drying up, while John Rhŷs thinks that the authors of the magic formula are a married couple, Atanto and Atanta, who begged the goddess Divona to give them a child.1706 The significance of this tablet-inscription remains then quite enigmatic. It seems nonetheless probable that this magical message is addressed to the goddess Dibona (=Divonna).

The poet Ausonius, in his 4th-century AD De claris Urbibus, who sings the beauty and purety of the Fountain of Bordeaux, reported that it was presided over in Celtic times by a goddess called Divona, whose name meant ‘divine’:

‘Salve, fons ignote ortu sacer, alme, perennis,vitree, glauce, profunde, sonore, illimis, opace

salve, urbis Genius, medico potabilis haustu

Divona Celtarum lingua, fons addite divis.

Hello, fountain the spring of which is unknown, holy fountain, beneficial, inexhaustible, crystalline, azure, deep, murmuring, limpid, shaded; Hello, Genius of the town, who pours us a salutary drink, Divona, which means divine fountain in the language of the Celts. 1707 ’

In the time of Ausonius, the fountain apparently flowed out from twelve taps into a basin in marble, but today the spring is no longer visible and its location is uncertain.1708 Robert Etienne has suggested it was situated at Saint-Christoly.1709 There is no archaeological evidence proving the worship of the goddess Divona in Bordeaux, apart from an altar bearing the inscription […]onae, which Jullian reconstructed as [Div]onae, but it could also be [Sir]onae, who is mentioned in other inscriptions from Bordeaux.1710

An altar discovered in 1849 on the oppidum* of Laudun, situated near Bagnols-sur-Cèze (Gard), bears the following inscription: Diiona, which could be read either Deona or Divona.1711 This would be the ancient name of the stream L’Andiole, called La Vionnein the 18th c., which rises in the commune of Saint-Marcel-de-Carreiret (Gard) and flows into the river Cèze at the Moulin Bez, in the commune of Sabran (Gard).1712 The inscription could thus be a proof of the cult of the goddess Divona.

Finally, in Ireland, it is interesting to note that the names of several rivers are derived from the Old Irish Bandea or Bandae and Modern Irish Bandia, composed of ban (‘woman’) and dia (‘deity’), that is ‘the Goddess’. These include the River Bann (an Bhanna) in Ulster, the River Bann (an Bhanna) in Co. Wicklow, the River Banna (an Bhanna) in North Antrim and the River Bandon (an Bhanda) at Kinsale in Co. Cork.1713 The construction Bandae, being a compound, replaced the earlier Celtic form Deva in the early Old Irish period.

All those deva, divonna, banna names, generally given to rivers and springs in Ireland, Britain and Gaul, clearly evidence that water was regarded as sacred in ancient times and deified as a goddess inhabiting its bed; the concept being significantly attested in Irish mythology.