d) Iconography

The celebrated bronze statue of Sequana, dated 1st c. AD, was discovered together with the bronze statue of a faun in a riff of the cliff overhanging the site by Corot in 1933.1825 These statues may have been hidden there in a time of insecurity, possibly when the first Barbarian invasions swept the area in 275 AD.1826

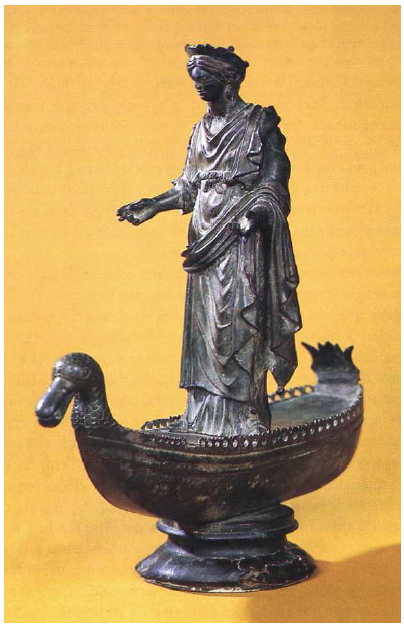

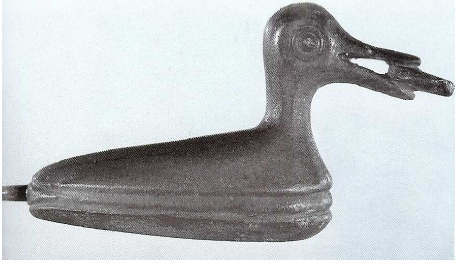

The representation of the goddess is very classical: she wears a diadem, a chiton* and a pallium* (fig. 12).1827The only element which is of indigenous character is the boat on which she stands. Its peculiarity resides in its stern which is in the form of a duck tail and in its prow which is in the shape of a duck head, holding a round fruit, a pearl, a cake or pellet in its beak.1828 Similar images of ducks with a cake or a pellet in their beak have been found at Ashby-de-la-Launde (Lincolnshire), Rotherly Down (Wiltshire) and at the Iron Age hillfort of Milber Down (Devon), where the duck is represented swimming, for the water-line is drawn along its body (fig. 13).1829 Terracotta figurines of ducks in skiffs were also discovered in Vichy (Allier) and Pourçain-sur-Besbre (Allier) in funerary tombs of children.1830 In the representation of Sequana, the duck obviously symbolizes the water of the river.1831 Deyts argues that this statue must have been offered by merchants, traders or boatmen, who wanted to honour the protectress and benefactress of water-borne trade on the River Seine.1832 This would suggest that the cult of Sequana was not related to healing only but also to commerce and waterways. She may have simultaneously presided over sick pilgrims and tradesmen.

The 1st-century AD statue in limestone, found by Baudot in 1832, representing a goddess seated in a chair and wearing a pleated tunic, might also be a representation of the goddess Sequana, for it was found in the room facing the first sacred spring (see fig. 22).1833 Moreover, the sitting position is a mark of pre-eminence generally reserved for deities. This room might thus have been a small temple or canopy* where pilgrims could come, collect their thoughts and pray to the goddess. The head and arms of the statue are now missing (fig. 14).