e) Votive offerings and Sanctuary

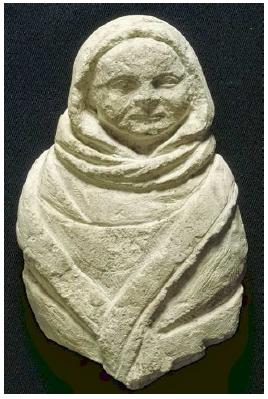

Apart from the ex-voto bearing a dedication to the goddess Sequana and the two statues, many other votive offerings were unearthed on the site, such as coins, personal offerings (rings, fibulas*, bracelets, necklaces or hairpins), reliefs* portraying swaddled babies or pilgrims and anatomic ex-votos* representing various parts of the body (legs, arms, breasts, pelvises, internal organs, etc). The series of swaddled infants (fig. 15) and full-sized male or female characters amounts to fifty-five images in stone and fifty in wood.1834 They are representations of the pilgrims who came to the sanctuary to honour and pray to Sequana for their vows to be fulfilled. The reliefs* generally portray them wearing the bardocucullus* (fig. 16), or holding symbolical offerings, such as a piece of fruit, a dog, a rabbit, fowl or a purse, in their hands (fig. 17).1835Some of them are also pictured with a ‘straps-and-medallion’ motif on chest and back, a garment which might have been a kind of talisman specifically worn for the pilgrimage to the sacred site (fig. 17).1836

The impressive series of anatomic ex-votos*, consisting of 319 pieces in stone, 247 in bronze and 253 in wood, proves that Sequana was worshipped as a healer.1837 People would come to the shrine and deposit a representation of the body part which was sore or diseased for Sequana to cure it. Sequana was not specialized in curing particular ailments, since all the parts of the human body are represented: heads and busts (127 in stone, 80 in wood, 5 in terracotta); torsos, trunks, pelvises (39 in stone, 120 in bronze, 13 in wood); legs and feet (100 in stone, 4 in bronze, 45 in wood) (fig. 20); arms and hands (43 in stone, 11 in wood) (fig. 20), eyes (119 plaques in bronze) (fig. 18) and internal organs (4 in bronze, 53 in wood) (fig. 19). Sculpted faces with half-closed eyes may be representations of blind people, while distorted legs, arms or feet may point to particular disabilities.1838 As for the internal organs, such as pharynxes, larynxes, lungs, open or closed ribcages, intestines and kidneys, they are ‘stylized’ representations which do not accurately reproduce the internal human body. Gaulish people actually had little knowledge of the shape and functions of the internal organs, because they did not dissect human beings.1839

The impersonality and similarity in the 119 bronze plaques picturing eyes and the ninety-one representing pelvises tend to indicate that the ex-votos were mass-produced and sold on the site. Very few anatomic ex-votos* indeed bear a name, apart from the bronze plaque with eyes signed by a Celtic woman Matta(fig. 21)1840 and the plaque with breasts offered bySinuella (fig. 8). They were probably made by artisans who used local materials, such as the oolitic limestone of the surrounding cliffs and the oak growing on the plateau, which were easy to extract and shape.1841 Their workshops were certainly situated inside the sanctuary so that the pilgrims could buy their offerings on the spot.

It is interesting to note that about 2,000 bone fragments belonging to around 193 domestic and wild animals, such as oxes, pigs, sheep, goats, horses, dogs, chickens, stags, boars, foxes and hares, were also discovered by Deyts in the marshy area of the sanctuary.1842 Wild animals are on the other hand very little represented. Pig and the sheep predominate among the domestic animals. This evidences that animals were sacrificed and that religious rites aiming at honouring the goddess must have been held on the site.

Although the waters of the River Seine had no mineral or therapeutic virtues, these anatomic ex-votos* prove that Sequana was a salutary goddess who was prayed to and worshipped for her healing powers.1843 Deyts, who proposes a reconstitution of the sanctuary in Gallo-Roman times (fig. 22), explains that sick pilgrims would come to the sanctuary, perform ablutions* in one of the sacred springs and stop at the temple - the fanum* discovered by Martin – to pray to the goddess for help.1844 They would buy an image of their diseased body part in a stall situated in the enclosure of the sanctuary and offer it to the goddess while making a vow of recovery. The ex-votos may have been heaped up onto shelves or placed on the floor in the gallery of the temple, under the portico or maybe in the open air. From the layout of the sanctuary, Deyts infers that there may have been an incubation portico, that is a place where the sick people would spend the night in order to encounter the deity in their dreams and thus recover more quickly.1845

The priests, who were regarded as intermediaries between the gods and the pilgrims, would interpret the dreams, treat the sick people, and offer them advice and remedies in the name of Sequana. The tradition of incubation is not originally Celtic and was certainly brought from ancient Greece, where it was particularly in use, such as at the 6th-century BC sanctuary of Epidaurus, situated in the north-east of Pennopolese, which was one of the most famous healing centres of Greece dedicated to the god-physician Asclepius.1846 After the whole ritual of ablutions*, prayers and deposit of ex-votos, the pilgrims would later come back to the sanctuary and bring various kinds of offerings to thank the goddess for accomplishing their vows. Dedications to Sequana bearing the votive formula v(otum) s(olvit) l(ibens) m(erito), ‘(the dedicator) paid his vow willingly and deservedly’ indeed indicates that vows had been granted by the goddess.

The sanctuary, which dates from the 1st c. AD, is Gallo-Roman. Coins discovered on the site prove that it was still in use in the 4th c. AD.1847 Yet, it is clear that the goddess and the place of worship predate Gallo-Roman times, since Sequana’s name is Celic. Moreover, a significant number of the dedicators are peregrines bearing Celtic names, such as Sinuella, daughter of Vectius, and Dagolitus, the sculptor. Others are peregrines bearing Latin names but their father’s names are Celtic: Lucius, son of Nertecomaros and Mariola, daughter of Maiumilus or Mattuus. The fact that the father chose a Latin name for his son or daughter shows his desire to become Romanized. Nonetheless, despite his Romanization, the dedicator honours a Celtic deity, which proves his attachment to his original roots and cults. Similarly, Clementia Montiola, who bears the duo nomina of Roman citizens, must be of Celtic origin, since her second name is Gaulish. As for Rufus and Hilaricus, they definitely have Latin names, but their unique names indicate that they are not Roman citizens. Accordingly, all of them, except for Flavia Favilla, are peregrines of Celtic origin in the process of Romanization. Furthermore, it can be noted that none of the dedicators held official functions in Roman Gaul. From this, it follows that the sanctuary was mostly frequented by local people in Gallo-Roman times and that it must originally have been an indigenous place of devotion.