c) The Tomb-Boat in the River: Funerary Dimension

As mentioned above, the river simultaneously symbolizes life and death. The mother-river is the one who gives birth and maintains people alive thanks to her waters, but she is also the one who takes life back when she decides to flood inhabitants, crops and livestock: human beings metaphorically return to her womb, representing thus the eternal cycle of renewal. This concept is illustrated by various proto-historical ‘coffin-pirogues’ found in the bed of some rivers. Those tomb-boats, called Todtenbaum, i.e. ‘Tree of Death’ by Joseph Xavier Boniface Saintine, a 19th-century philosopher, consisted of a hollowed tree trunk serving as a boat where the corpse of the deceased was placed before abandoning it to the river’s current.1859

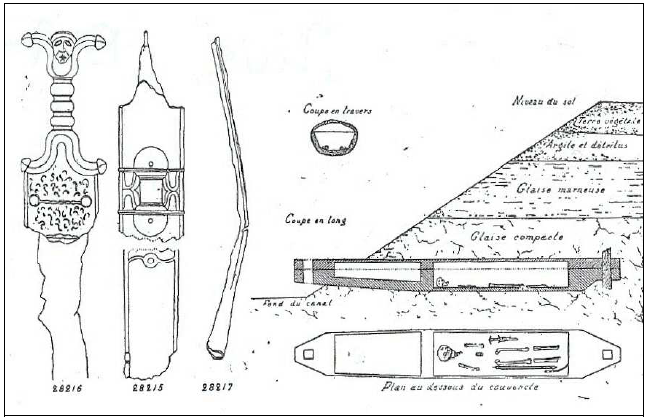

Saintine reports the discovery of tree trunks containing the remains of human beings in 1560 in the Zuyder Zee, an inlet of the North Sea in the north-west of the Netherlands, but he does not give his references. This practice is proved by several examples of ‘tomb-boats’ discovered in Gaul. The most illustrious instance is the boat-tree found during repair works in the canal connecting the Marne to the Rhine at Chatenay-Mâcheron (Haute-Marne), a place situated 5 kilometres from Balesmes-sur-Marne, where the river rises.1860 The monoxylic pirogue* is 5-metre long and carved out in an oak trunk (fig. 25 and 26). It is composed of two parts: a lid and a hollowed part which contained a human skeleton and three weapons, which are an iron sword in an ornamented scabbard, an iron spear and an iron dagger with a bronze handle representing a human head, called ‘anthropoid dagger’. This wooden vessel, dating to the 3rd-1st century BC, was therefore used as a sarcophagus. The weapons tend to prove that the deceased was an honoured prince or warrior. Three similar pirogues, probably dating from the Late Bronze Age or La Tène period, containing skeletons wearing copper rings, and another one enclosing a human skull and two thighbones, were discovered in 1780-1781 and 1787 on the bed of the River Orne, at Mondeville (Calvados), and in Caen, near the bridge of Vaucelles (Calvados).1861 In Le Havre (Seine-Maritime), between 1788 and 1800, a thirteen-metre long monoxylic pirogue* containing human remains was found in the ornamental lake of La Barre during repair works.1862 Finally, a four-metre long hollowed oak tree containing a whole skeleton was dredged from the bed of the River Saône at Montseugny (Haute-Saône).1863 Apart from the coffin-pirogue from Chatenay-Mâcheron (Haute-Marne), now housed in the Musée des Antiquités Nationales (Saint-Germain-en-Laye), the other ones were unfortunately left in open-air when discovered and crumbled into dust a few weeks later.

Those boat-sarcophagi point to a funerary rite which consisted of returning the deceased to the bosom of the ‘mother-river’ who would ensure his rebirth in the afterlife. As Gaston Bachelard, a renowned French philosopher of the first half of the 20th c., explains, the river and the tree are two powerful maternal symbols; the combination of the two elements thus enhances the funerary dimension:

‘Water, substance of life, is also the substance of death for ambivalent reverie. In order to interpret the Todtenbaum, the Death Tree, accurately, we must keep in mind with Carl Gustav Jung, that “the tree is, above all, a maternal symbol”; since water is also a maternal symbol, a strange image of the encasing of seeds may be grasped in the image of the Todtenbaum. By placing the dead person in the interior of a tree and entrusting the tree to the breast of the waters, one doubles the maternal powers; the myth of the doubly, Jung tells us, because we imagine that “the dead person is given back to his mother to be borne again.” Death in water will be, for this reverie, the most maternal of deaths. The desire of man, says Jung in another place, “is that somber waters of death may become the waters of life, that death and its cold embrace may be the maternal bosom [...]”.1864 ’This funerary practice is redolent of the belief in the voyage to the Beyond: the boat symbolically brings the deceased to the otherworld, which was believed to be situated under the waters of rivers and lakes.

This tradition, which goes back to prehistory, is practiced among certain present-day peoples, such as the Toradja of central Sulawesi (Indonesia), who called it a bangka (‘boat’) or jomu (‘covering’),1865 and the Jivaro Achuar and Canelos of Ecuadoran Amazonia.1866 Speaking of the ‘tomb-boat’ funerary custom of the Canelos, Raphael Karsten explains that they believed “the deceased […] ought to make his last journey in a canoe”.1867 This ancient belief has survived in the folklore of the west of France. Paul Sébillot reports that in the swamps of the province of Poitou,1868 a mysterious boat covered with a white sheet resembling a pall, called niole blanche (‘white skiff’), or la niole de l’angoisse (‘the skiff of anguish’), was believed to appear in the canals of the marshes.1869 It was steered by a ghost called the tousseux jaune(‘the yellow coughing one’), who would bring death to any person catching sight of him. The death-boat is a particularly recurrent theme in the oral tradition of the coast of Brittany. Sébillot, relating a legend recorded by the Byzantine historian Procopius in the 6th c., describes boats loaded with souls of deceased people seen at night crossing the sea:

‘The legend of the boat of the dead was one of the first to be formulated on our shores; it no doubt existed here well before the Roman conquest, and in the sixth century, Procopius reported it in these terms: The fishermen and other inhabitants of Gaul who are across from the island of Britannia are entrusted with passing souls over to it and are thus exempt from paying tribute. In the middle of the night, they hear a knocking at their door; they get up and find strange boats along the shore in which they can see no one but which, nevertheless, seem so loaded down that they are about to sink and their gunwales scarcely a thumb’s width above the water. An hour suffices for the crossing, although with their own boats they have difficulty making it in a whole night.1870 ’The motif of the death boat is also found in the folklore of Ireland. There are traditions in many coastal parts of Ireland concerning phantom ships or boats seen at sea.1871 They can be seen before some sea-disaster, as if they have come to take away the people who are destined to be drowned. Also they can be seen after a shipwreck, in which case they are definitely taking away the souls of the drowned people. These phantom vessels are sometimes lit up. Ó hÓgáin relates that in the Irish-speaking parishes of An Rinn and An Seana-Phobal, on the coast near Dungarvan in County Waterford, in the south of Ireland, people talk of a phantom ship called Bád na Soilse, literally ‘the Boat of Lights’, which is much feared.1872

Those discoveries thus prove that the river-goddess, in addition to her virtues of fertility and healing, must have had a funerary function. As a mother, she protected her people both in life and in the afterlife, and ensured their voyage to the otherworld.