3) The River Saône: Souconna

The River Saône, which has its source in Vioémnil, at the foot of the Monts Faucilles (Vosges), and flows into the river Rhône in Lyons (Rhône), had two different names in ancient times: Arar and Souconna.1873 Greek and Latin authors, such as Pliny, Silius Italicus, Seneca, Tacitus, Caesar, etc., refer to the River Saône as a calm river which they call Arar, Araris and Araros.1874 The name Souconna appears in a 1st-century AD votive inscription dedicated to the goddess of the River Saône. Around 360 AD, Ammianus Marcellinus, one of the last Roman historians of Antiquity, reports that “the Arar is called Sauconna” (Ararim quem Sauconnam adpellant).1875 It can be noticed that in the 4th c. AD, the form Souconna had changed into Sauconna. The name then evolved into Saogonna or Sagonna in the 7th c., Saone in the 12th c., Soone in the 14th c. and Sone in the 15th c and gave the present-day name of the River Saône.1876

The meaning of Souconna remains obscure. According to Olmsted, Souconna is derived from an IE root *sūk- signifying ‘juice, sap, moisture, rain’, ‘to suck’ and means ‘the Suckler’, ‘the Flowing One’, but this etymology* remains conjectural and uncertain.1877 Evidence of her cult was found in two different places: on the bank of the River Saône, in Chalon-sur-Saône (Saône-et-Loire), and near the spring of the brook of the Sagonin, in the village of Sagonne (Cher).

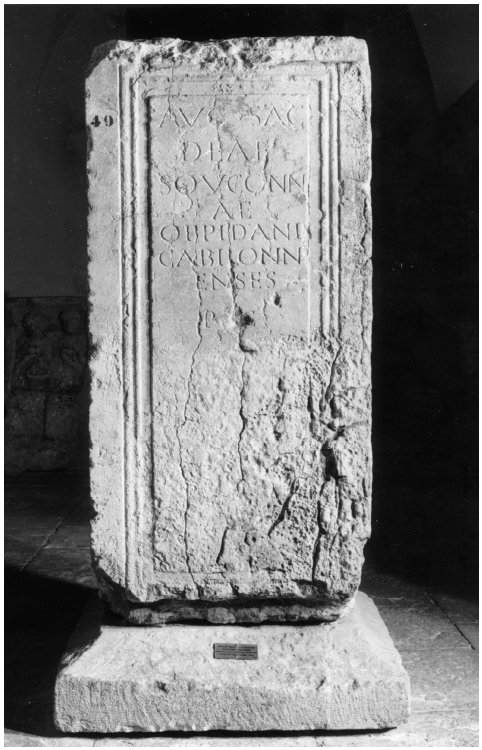

The inscription from Châlon-sur-Saône is engraved on a pedestal in limestone, probably dating to the end of the 1st c. AD, found in 1912, in re-employment* in the 3rd or 4th-century wall of the city.1878 The inscription is the following: Aug(usto) sac(rum) deae Souconnae oppidani Cabilonnenses p(onendum) c(urauerunt), ‘Sacred to Augustus, to the goddess Souconna, the inhabitants (oppidani) of Chalon took care to build (this monument)’ (fig. 27).1879 This dedication is offered by the inhabitants of the Gaulish oppidum* of Chalon-sur-Saône, called Cabilonnum.1880 Chalon-sur-Saône was probably the second chief oppidum* of the tribe of the Aedui after Bibracte (see Chapter 3).1881 As the inscribed pedestal was originally associated with a statue representing the goddess, it was assumed that before being re-employed in the wall of the city, it belonged to a temple. Excavations carried out in 1852 at a nearby place known as Châtelet, which revealed various architectural fragments, led some scholars to think that a temple dedicated to Souconna had been erected there, but there is actually no cogent evidence supporting such a hypothesis.1882

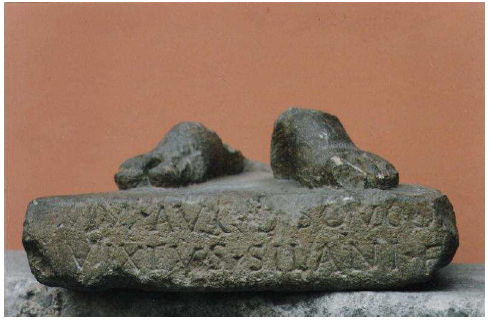

A second inscription dedicated to the goddess Souconna was found in 1899 at a place known as ‘Les Maisons Neuves’, in the village of Sagonne (Cher), near the place where the brook called the Sagonin has its source.1883 The inscription is engraved on a small pedestal in stone, where only the naked feet of the goddess remain: [N]um(ini) Aug(usti) D(eae) Souco[nae Di]vixtus Silani f(ilius), ‘To the divine power of Augustus, to the goddess Soucona, Divixtus, son of Silanus (offered this)’ (fig. 28).1884 The dedicator Divixtus and his father Silanus have Gaulish names - Divixtus means ‘to avenge’, ‘to punish’.1885 Furthermore, they bear the unique name, which means that they are not Roman citizens but peregrines. This tends to prove that the cult of the goddess Souconna was prior to the Roman invasion. It is interesting to note that Soucona, Saucona and Sagona are variants of the same name, which would explain why the goddess Souconna was honoured in the village of Sagonne, near the brook of the Sagonin.1886 As the dedication was discovered near the source of the brook, it can be assumed that Souconna was the personification and protectress of the spring. At this place, archaeologists also unearthed a bronze Gaulish coin, with a curly head on the obverse and an eagle on the reverse, five small bronze coins with the effigies of Tetricus (271-273 AD), Constantinus I (306-337 AD), Valentinienus I and his brother Valens (364-378), fragments of sculpted stones, statues and several hands and arms, which might point to a healing cult, but this remains hypothetical, since the objects are now lost.1887

A relief* discovered near Seurre (Côte d’Or) might be a figuration of Souconna (fig. 29).1888 The goddess is represented standing with a diadem and a pleated tunic falling under her right breast. A small boat, an upside-down urn with water flowing from it, and a trident, are situated at her feet on the right-hand side. On account of those attributes, which symbolize water, the goddess is clearly the personification of a river. As Seurre is situated on the bank of the River Saône, Claude Bourgeois thinks she is its embodiment.1889 It is not possible to affirm that this relief* is definitely a portrayal of Souconna, since it is not combined with an inscription identifying the goddess. Espérandieu suggests that she might have been the tutelary goddess of Seurre, personifying and protecting the city.1890