5) The River Wharfe: Verbeia

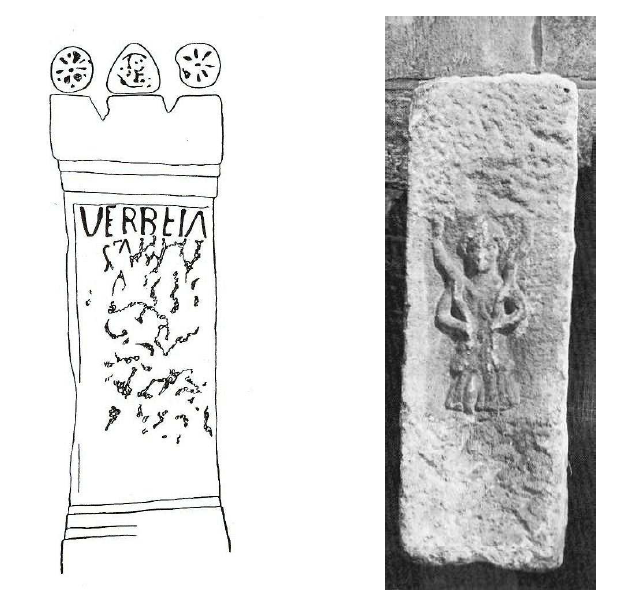

The goddess Verbeia is mentioned in a single inscription engraved on an altar, discovered before 1600 at a place known as Stubham Lodge, near Ilkley (Yorkshire, GB). On the right side of the stone is drawn a patera* and on the left side a guttus*. The inscription reads: Verbeiae sacrum Clodius Fronto praef(ectus) coh(ortis) II Lingon(um), ‘Sacred to Verbeia Clodius Fronto, prefect* of the second Cohort of Lingonians (set this up)’ (fig. 31).1901 The dedicator bears the duo nomina of Roman citizens and is prefect* (praefectus) of Cohort* II, called Lingonum, attested by other inscriptions from Ilkley and Moresby and by a Hadrianic decree.1902 Clodius Fronto pays homage to the goddess Verbeia, who is generally understood as being the personification of the river Wharfe, on which Ilkley is situated.1903

Heinrich Wagner and Anne Ross propose to relate her name to the Old Irish root ferb, ‘cattle’ and translate her name as ‘She of the Cattle’, which would link her to the Irish river-goddess Bóinn, whose name signifies ‘the Cow-White (Goddess)’, and to the Gaulish spring-goddess Damona, the ‘Cow (Goddess)’.1904 This etymology* remains conjectural.

A relief* of a goddess wearing a long, pleated sleeveless tunic and holding a snake in each hand, discovered in re-employment* in the parish church of Ilkey, could be a representation of Verbeia (fig. 31).1905 As Ross and Green point out, the snake image might point to a water cult.1906 It must nonetheless be borne in mind that there is a wide range of complex symbolism attached to this animal, which was represented in various contexts and accounted for diverse aspects. It was notably an emblem of the otherworld, death, medicine and fertility.1907 Consequently, it is impossible to determine whether the relief* is a figuration of the goddess Verbeia.

We have seen that the worship of river-goddesses in Celtic and Gallo-Roman times is widely attested in the epigraphy of Gaul and Britain, and in the ancient literature of Ireland. The fact that the goddess is eponymous of the river proves that she was envisaged as the personification of the river. The pattern of the lady drowned in the river, found in the legends of Bóinn, Sionann, Eithne and Érne, is evocative of that ancient belief. The early legend of Tochmarc Emire [‘The Wooing of Emer’], which depicts the River Boyne as the body of the goddess Bóinn, is also illustrative of this river-goddess complex. While the Irish medieval texts indicate that Irish river-goddesses incarnated wisdom and were believed to bestow mystical knowledge on the ones who drank their waters, archaeology evidences that Gaulish river-goddesses were worshipped as healers, who brought relief to pilgrims through their salutary waters. In Gaul, moreover, the healing function was not only attributed to goddesses of rivers. Many wells, fountains and springs were worshipped and put under the patronage of goddesses, who seem to have also fulfilled that role in view of the archaeological context or the curative properties of the waters.