A) Fountain-Goddesses

1) Acionna and the Fountain l’Etuvée (Loiret)

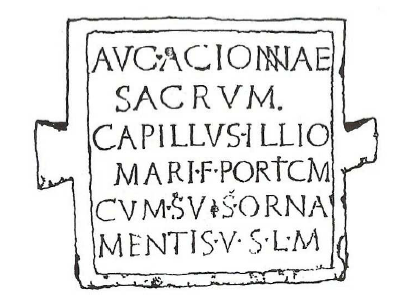

The goddess Acionna is known from an inscription discovered in 1823, thirty-five-metres deep in a well, called the ‘Fontaine l’Etuvée’, situated at a place known as the ‘Clos de la Belle-Croix’, 2.5 kms from Orléans (Loiret), in the territory of the tribe of the Carnutes.1908 The inscription, engraved on a quadrangular block, reads: Aug(ustae) Acionnae sacrum, Capillius Illiomari f(ilius) portic[u]m cum suis ornamentis, v(otum) s(olvit) l(ibens) m(erito), ‘Sacred to the August Acionna, Capillius, son of Illiomarus, (offered) this portico with its ornaments and paid his vow willingly and deservedly’ (fig. 32).1909

According to Jean-Baptiste Jollois, the stele* must date from the 1st c AD.1910 The two tenons* on the two sides of the stone indicate that the stele* was hung up or embedded in a wall.1911 It was a common tradition to hang up inscribed stones or bronze plaques on the wall of a temple or of a well in Gallo-Roman times to pay homage to a deity. This inscription mentions that the dedicator had a portico built in recognition of the fulfilment of a vow. The portico might have been part of a religious edifice erected in honour of Acionna, but no archaeological data provide evidence of such a monument in the area. The dedicator Capilliushas a Roman name, but is not a Roman citizen, since he bears the unique name. As for his father, he has a Gaulish name: Illiomarus, which is composed of illio- (?) and marus, ‘great’ - also known in the form Ibliomarus.1912 The fact that the Celt Illiomarus chose a Latin name for his son reflects his wish to become Romanized. In paying homage to a Celtic goddess, Capillius however shows his attachment to his indigenous roots and cults.1913

The ‘Fountain l’Etuvée’, commonly called ‘de Lestuvée’, ‘de l’Estuif’ or ‘de l’Estuivée’, from Old French etui(f) and English stew, signifying ‘fish-tank’, supplied all the thermal and swimming establishments of Orléans with water until the18th c., when it dried up, probably after being deliberately obstructed.1914 In 1823, Jollois decided to excavate the spring, because its profuse waters could be harnessed to supply the network of public fountains of Orléans.1915 As the spring of l’Etuvée was the result of the rains falling on the thickly-wooded plateau of Fleury, it is highly likely that the spring was copious in ancient times - forests are the main cause of the formation of fountains. The first excavations brought to light a big quadrilateral basin, a small duct harnessing the spring and a well 3.5m in depth, constructed with pieces of timber, where many Roman remains were discovered, such as fragments of tiles and pottery, a cinerary urn, clay bowls and dishes, a small flint axe, a bronze hook and the inscribed stone to Acionna.1916 From 1971 to 1989, the excavations were resumed and two square basins, one of which was surrounded by a wall, were discovered.1917

Acionna’s name is known from two other fragments found in re-employment* in the Roman wall of the city of Cenabum(Orléans) and in an ancient wall situated at the corner of the streets of the Ecrevisse and of the Hôtelleries. The two fragments being very damaged, their reconstitution is uncertain. The first one reads: [Aug. Aci]onn(a)e [ … e]t Epade[textorigi . . . ], ‘Sacred to Augustus and to Acionna […] and Epadetextorix (?)’.1918 The co-ordinating conjunction et indicates that the inscription was offered by two dedicators. Léon Dumuys reconstituted the name of the second dedicator as Epađetextorix, in view of an inscription from Néris-les-Bains (Allier) which mentions this name.1919 Delamarre proposes to break it down as *Epađ-atexto-rigi, with epađ similar to epo-, ‘horse’, atexto, possibly ‘belongings’ and rigi, ‘king’, that is ‘the king who possesses horses (?)’.1920 As for Robert Mowat, he suggests to translate his name as ‘protective lord of horses’, with epo- ‘horse’ and actetorix ‘protective chief’.1921 Since Epađetextorix bears the unique name, he is a Celtic peregrine*. The second fragment is uncertainly dedicated to the goddess: [Acionna]e sacrum, ‘Sacred to Acionna (?)’.1922

As regards Acionna’s name, it is undeniably Celtic, but its significance remains obscure. According to Delamarre, it is based on a root aci-, the meaning of which is unknown.1923 Olmsted advances that it might come from a Celtic root acio- signifying ‘water’, derived from the IE *akuio-, but Delamarre and Lambert do not list that term.1924 Even though this etymology* is dubious, it seems clear that Acionna is a goddess associated with water; since it is possible to establish a connection between her name and several names of rivers flowing near Orléans. The River Essone, which has its source in the north of the forest of Orléans and meets the River Seine at Corbeil-Essone (Essonne), was called Exona or Axonia in the 6th c. and Essiona in 1113.1925 Another river called The Esse or Stream of the Esse, which rises in the forest of Orléans and flows into the River Bionne, may be also related to the goddess name Acionna.1926 Finally, the Aisne, which rises in Sommainse (Meuse) and joins the River Oise at Compiègne (Oise), was called Axona in the 1st c. BC, Axuenna in the 3rd c., Axina in 650 and Axna in 824.1927

These various discoveries show that the fountain of L’Etuvée was worshipped in Gallo-Roman times and that it was presided over by the Celtic goddess Acionna. It is impossible to determine whether the waters of the well were believed to have medicinal properties and whether Acionna was revered as a healer, since anatomic ex-votos* evidencing such a cult were not found on the site. The phrase V.S.L.M. does not imply the fulfilment of a vow of recovery either. Moreover, the waters do not have any mineral or thermal virtues today.1928 Acionna is probably best understood as a local water-goddess, since the three inscriptions were found in and around Orléans, and since her name has survived in two rivers rising in the forest of Orléans: the Essonne and the Esse. The fact that her name can be connected to the River Aisne, situated to the north-east of Paris, might nonetheless indicate a wider cult. Acionna being honoured by dedicators of Celtic origin, such as Capillius, son of Illiomarus, and Epađetextorix, her cult was pre-Roman. It also shows that the Gaulish traditions, beliefs and deities remained still vividly alive in people’s minds for some time after the Roman conquest.