a) The inscriptions and the Nympheum*

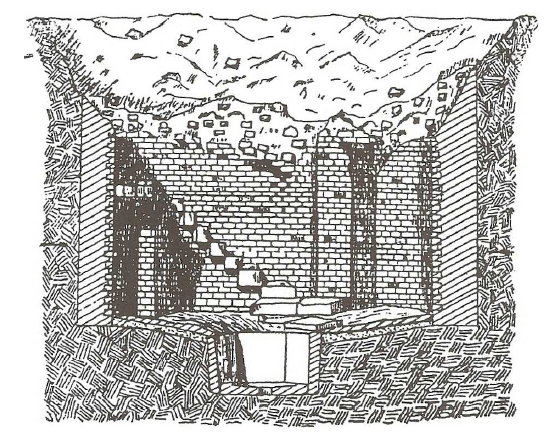

The five inscriptions to the goddess Icovellauna were discovered in an underground octagonal well, six metres in diameter, dating from the Gallo-Roman period, excavated between 1879 and 1882 in the sand-quarry of Le Sablon (fig. 33).1935 About fifty stairs went down to a spring, contained in a polygonal basin situated in the middle of the edifice.1936 Hundreds of votive offerings, such as coins, statuettes, animal bones and fragments of columns, were discovered in the rubble of the well.

The first inscription is engraved on a bronze plaque with two holes in the top left- and right-hand corners, which served to hang the plaque on the wall of the well, and leave it as an ex-voto for the goddess. It seems that it was originally gilded, but copper oxide almost entirely covered the plaque when it was discovered. The inscription is the following: Deae Icovellaunae sanctissimo numini, Genialius Satu[r]ninus v(otum) s(olvit) l(ibens) m(erito), ‘To the highly holy power of the goddess Icovellauna, Genialius Saturninus, paid his vow willingly and deservedly’.1937 A hole, in which a coin could fit, is situated directly above the inscription. It might have been the coin at the effigy of Constantine (beginning of the 4th c. AD) found near to the bronze plaque.1938 This space for fitting a coin or a medal is called ‘case monétaire’ or ‘écrin à médailles’. Examples of this type are the famous patera* in gold from Rennes or ‘the plaque of Hiéraple’ dedicated to the god Visucius.1939 The use of the votive formula dea proves that the inscription dates from the second half of the 2nd c. AD or the beginning of the 3rd c. AD.1940 The dedicator has Latin names and bears the duo nomina of Roman citizens. The phrase v.s.l.m. indicates that Genialius Saturninus is grateful to the goddess Icovellana for answering his vow and the expression sanctissimo numini attestshis profound respect.

The second inscription is very similar to the first, for it is engraved on a fragment of a bronze tablet, which also has two holes at each top corner and a ‘case monétaire’, which might have been fitted with the coin at the effigy of Crispus (beginning of the 4th c. AD) found near the dedication. The reconstitution of the inscription, which is damaged on the left side, remains tentative: [Deae] Icov(ellaunae maxi)mus Licini(us magister vic)i (?) v(otum) s(olvit) l(ibens) m(erito), ‘To the goddess Icovellauna, Maximus Licinius, Master of the vicus* (?), paid his vow willingly and deservedly’.1941 Charles Abel suggests that Maximus and Licinus are the names of two different Mediomatrici citizens, but it is more likely that they are the duo nomina of a single dedicator.1942Maximus Licinius was thus a Roman citizen and might have been in charge of governing and administering the vicus*.

Three other fragments of dedications were discovered in the nympheum*. The first one is engraved on a slab: [Deae Ic]ovellau[ae Ap]rili[s], ‘To the Goddess Icovellauna Aprilis […]’;1943 the second is engraved on a block in white stone, which seems to have belonged to a square pedestal: D[eae] Icov[ellaunae], ‘To the goddess Icovellauna’;1944 and the third one is inscribed on a piece of white marble: Deae I[covellaunae], ‘To the goddess Icovellauna’.1945

Finally, a dedication engraved on a stone was discovered in 1891 in Trier, in the territory of the Treveri, who neighboured the Mediomatrici. The inscription reads: Deae Icovel(aunae) M(arcus) Primius Alpicus v(otum) s(olvit) l(ibens) m(erito), ‘To the goddess Icovellaune, Marcus Primius Alpicus, paid his vow willingly and deservedly’.1946 The dedicator has Latin names and bears the tria nomina of Roman citizens. He offers this stele* in recognition of the fulfilment of his vow.

The dedications prove that the spring of Le Sablon was under the patronage of the goddess Icovellauna, who probably healed people through the restorative qualities of her waters. This cannot however be ascertained with certainty, since anatomic ex-votos* evidencing such a cult were not found in or nearby the well. Icovellauna’s cult was certainly quite important in the area, since a worshipper, probably a member of the Mediomatrici, honoured her in Trier. This inscription also suggests that Icovellauna was not only a local goddess protecting the spring of Le Sablon but a goddess presiding over waters in general.