3) Mogontia (Le Sablon?)

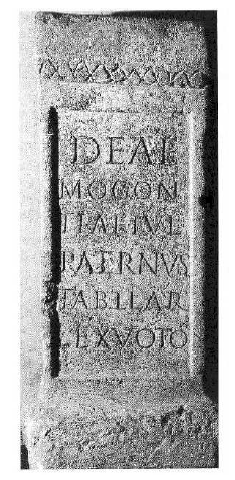

The goddess Mogontia is known from a single inscription engraved on a small quadrangular altar in white stone, found in 1880 in the sand quarry of Mey, situated about 100 metres to the west of the octogonal well of Le Sablon dedicated to goddess Icovellauna, in the territory of the Mediomatrici.1955 The altar was discovered among tiles, remains of the roof of an ancient public lavatory, vermiculated bricks, fragments of plaques, remains of the pavement of a temple, fragments of black and white marble and a winged statue representing the Roman goddess Victory.1956 The inscription is very well preserved and must date from the time of Titus Aelius Antoninus Pius, which is to say from the middle of the 2nd c. AD. The inscription reads: Deae Mogontiae Julius Pa[t]ernus tabellarius ex voto, ‘To the goddess Mogontia, Julius Paternus, tabellarius, offered (this)’ (fig. 34).1957 On the altar, above the inscription, there is an oblong cavity (24 cm x 8cm) with round tips, in which an undetermined object was apparently fixed by three tenons* - the holes can still be seen.

The dedicator Julius Paternus bears Latin names. He is a tabellarius, that is a messenger or bearer of letters.1958 The tabellarii were generally men from a very modest background, such as slaves or emancipated slaves, who held a public or private position. The public tabellarii were hired by the tax department, either to work for the postal service - since its reorganization by Augustus - or in the service of some public offices, while the private tabellarii were servants, working for the emperors or particular people. Contrary to the private messengers, the public messengers generally bore a qualification indicating their specific role and position. As Julius Paternus does not have a particular qualification, he certainly belonged to the private class of the tabellarii and was the messenger of some private individual. It is worth noting that the name Paternus appears again on one of the stairs of the sacred well of Le Sablon presided over by Icovellauna – his name was roughly engraved, probably with a knife.1959 Thus, Paternus was undeniably a faithful pilgrim coming regularly to the religious shrine of Le Sablon to venerate and pray to the local goddesses.

Olmsted proposes that Mongotia is based on a Celtic element mogu-, mogo-, a byform* of magu-, steming from the IE *magho-, signifying ‘boy’ or ‘youth’.1960 Accordingly, Mongotia would mean ‘the Youthful’. She has some analogies with the names of certain British and Gaulish gods.1961 In Britain, she is etymologically related to the godMongoti venerated at Old Penrith, Plumpton Wall (Cumbria),1962 the god Mongoti Vitiris honoured at Netherby, Longtown (Cumbria),1963 the god Mogunti worshipped at Chesterholm (Northumbria) and at Old Penrith (Cumbria),1964 the god Mogonitus or Mogunus mentioned in inscriptions from Risingham (Northumbria),1965 and the god Moguntibus known from a dedication from High Rochester (Northumbria).1966 In Gaul, she may be etymologically cognate with the god Apollo Grannus Mogounus honoured in Horburg, near Colmar (Alsace),1967 the god Mogounus revered in Ronchers (Meuse),1968 and the god Mounus, who is mentioned in dedications from Beugnâtre (Pas-de-Calais) and Lezoux (Puy-de-Dôme) and from Risingham.1969 Being recorded in northern Britain and in the centre, east and north of Gaul, the cult of the god Mogons, whose name has a wide variety of spellings, was clearly widespread. This convinces some commentators that Mogons was a title applied to several deities rather than the signifier of a single god.1970 Scarcely anything is known about his possible attributes. As he is associated with Apollo Granus in one inscription, he might have been a healing god, but this remains to be proved. The god cannot thus shed light on the possible functions and character of the goddess Mogontia.

Mogontia is also cognate with the Mogontiones, who are honoured in a dedication engraved on a quadrangular stone found in Agonès (Hérault), now used as a base of a cross in the Church of Saint-Saturnin. The inscription is the following: [Matris? M]ogontionibus Ocrac[ius] Fronto Ocraci f(ilius) posuit, ‘To the Mogontiones Ocracius Fronto son of Ocracius erected (this monument)’.1971 The dedicator’s father is a peregrine* with a Celtic name. According to Delamarre, Ocracius may be broken down as *Au-crac and mean ‘Spotless’.1972 The dedicator bears the duo nomina of Roman citizens. It is interesting to note that his gentilice* is the name of his father, while his cognomen* Fronto is Latin. In keeping the name of his father and in paying homage to Celtic goddesses, the dedicator shows that despite his Romanization he is still attached to his ancient cults and beliefs.

The place of discovery of the inscription and the dedication itself do not bring any significant information on the character of the goddess Mogontia. It is therefore difficult to determine what her functions were in ancient times. As the inscribed stone was unearthed near to the water shrine of Le Sablon, it is possible that both Icovellauna and Mongotia were worshipped at this spring. Mongotia could therefore have been a goddess of salutary waters. Her name signifying ‘youth’ might be evocative of such a cult, since waters were believed to be regenerative and to conserve youth and life, as the archetypal ‘Fountain of Youth’ illustrates. As for Jullian, Holder, Bourgeois and Olmsted, Mongotia would have been the eponymous goddess of the city of Mogontiacum, later called Mogontia (the present-day Mayence, in Germany), which is located about 200 kms from Metz.1973 This is a possiblity, for some goddesses were indeed the personification and patroness of important cities, e.g. Bibracte, the eponymous goddess of the capital of the Aedui (Mont Beuvray, in Saône-et-Loire), or Tutela Vesunna, the eponymous goddess of the city of the Pertrocorii (Périgueux, in Dordogne).