4) Coventina’s Well at Carrawburgh (Northumbria)

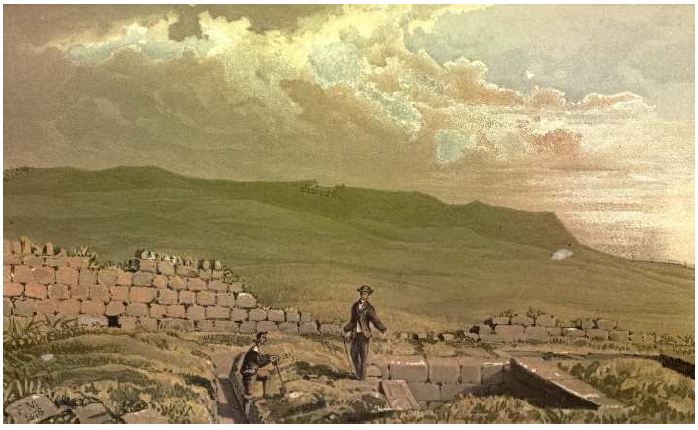

Coventina is a goddess known by twelve inscriptions unearthed in a well excavated from 1876 by John Clayton to the west of Carrawburgh Fort, near Hadrian’s Wall (Northumbria), in Britain (fig. 35).1974 To the south-east of the well were unearthed a Mithraeum* and a Nympheum*.1975 Lindsay Allason-Jones has given a comprehensive study of the well and its contents.1976 Coventina remains an enigmatic goddess. Various etymologies have been proposed for her name, but it remains difficult to determine its significance and whether it is Celtic or not. Alfred Rivet and Colin Smith linked Coventina to Latin cum, ‘with’ and vent, ‘market’ or ‘sale’, and demonstrated that it was not derived from the Indo-European language and could not be related to any Celtic derivations.1977At the end of the 19th c., Dr. Wake Smart proposed to relate it to the Welsh word gover signifying ‘a rivulet’ or ‘a head of rivulet’, while Dr. Hoopell assumed it was based on cov, ‘memory’ or cofen, ‘memorial’, and concluded that the reservoir was a cenotaph*. This theory however clearly does not suit the nature and structure of the shrine.1978 Charles Roach Smith then supposed the name was composed of convenio, ‘a coming-together’ and tina, which refered to the River Tyne quoted by Ptolemy.1979 According to him, Coventina’s name would refer to the confluence of the north and south rivers, but Allason-Jones rightly points out that it is located some distance away from Carrawburgh.1980 Hylton Dyer Longstaffe, taking up Smith’s idea, added that the first part of her name was composed of two parts con and went, which could refer to the stream Con and the River Went, which flow in Yorkshire.1981 In his view, Coventina was the name of three goddesses: con-went-tina, pictured as three Nymphs on a relief* discovered in the well (fig. 38); a theory which has no basis in the archaeological evidence. Finally, Norah Joliffe suggests that Coventina could be a goddess of a conventus, that is a community of German soldiers implanted at the Fort, but Allason-Jones argues that that is rather unlikely.1982 Allason-Jones concludes that the significance of Coventina’s name is undeterminable, but is undeniably Celtic.

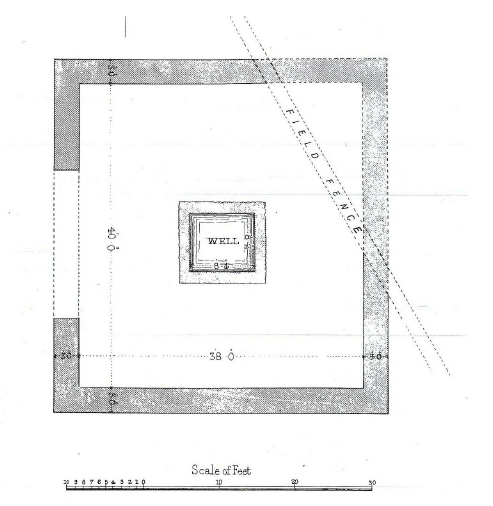

Coventina’s shrine consists of a large rectangular stone enclosure with a west door, in the centre of which is situated a rectangular reservoir, receiving the waters of several springs (fig. 36). The springs do not have particular medicinal properties and the votive offerings discovered in the reservoir do not point to a healing cult: anatomic ex-votos*, similar to those found at the Sources-de-la-Seine, have not been found. The various offerings are composed of inscriptions honouring the goddess; sculptures; jewellery such as brooches (10), finger-rings (14), hairpins (2), bracelets (5) and glass beads; animal bones; lead; leather and other objects. These clearly evidence that the waters were worshipped and placed under the patronage of Coventina.1983 The 16,000 coins fished up in the well prove that the shrine was visited from 128-130 AD until 378-388 AD.1984

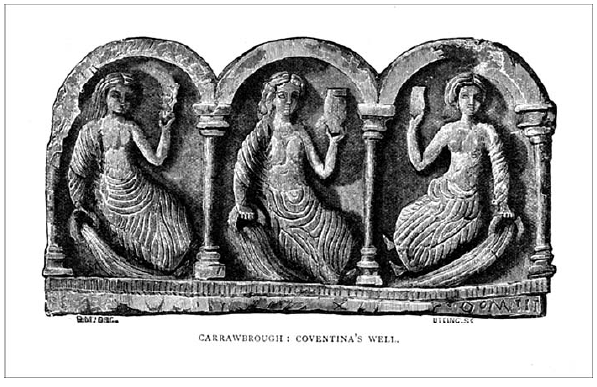

The inscriptions to Coventina are twelve in number. They are all listed and studied by Allason-Jones in her catalogue of sculpted stone and inscriptions.1985 One of them is particularly interesting, for it is combined with a representation of the goddess: Deae Couuentinae T(itus) D(...) Cosconianus Pr(aefectus) Coh(ortis) I Bat(auorum) l(ibens) m(erito), ‘To the goddess Covventina, Titus D(...) Cosconianus, prefect* of the First Cohort of Batavians, willingly and deservedly (fulfilled his vow)’ (fig. 37).1986 The dedicator bears Latin names and is a prefect*, that is a commander of the Cohors I Batavorum equitata, which came from Germany and was stationed at Carrawburgh in the 3rd c. AD.1987Coventina is pictured half-naked with a cloth around her hips, holding a leaf in her right hand and lying on an upside down urn from which water flows.1988 The position, the garment and the water-pitcher are typical attributes of water-goddesses and nymphs. This representation is very similar to the relief* discovered at the springs of Allègre-les-Fumades (Gard) in Gaul,1989 and to the other relief* discovered in the well, representing three Nymphs holding vases and pouring water from overturned pitchers (fig. 38).1990 Those Nymphs might be a figuration of Coventina in triple form but, as the stone is anepigraphic, it cannot be stated with certainty. It is more likely that the relief represents the Nymphs of Carrawburgh, who had a shrine dedicated to them near Coventina’s Well.

Out of the twelve inscriptions, Coventina is given the title of deae ten times, nymphae twice and sanctae once. This proves that she was a water-goddess presiding over the springs of Carrawburgh and that she was held in high respect by the population who came to visit the shrine and pray to her. Seven of the dedicators are Roman soldiers bearing Latin names: one is a decurio*;1991 two are prefects* of the First Cohort* of Batavians;1992 one is in the First Cohort* of Cubernians, which came from the Lower Rhineland and was garrisoned at Newcastle in the 3rd c.;1993 one is an optio* of the First Cohort* of Frixiavones;1994 and one is a soldier in an undetermined Cohort*.1995 As for Aurelius Crotus, who declares himself as a German, he bears Latin names and the duo nomina of Roman citizens.1996Two dedicators specify that they are German people,1997 and four dedicators are peregrines in view of their unique name: Vincentius bears a Latin name,1998 Madutus a German name,1999 and Vinomathus (?) and Bellicus have Celtic names.2000 It seems thus that Coventina was particularly celebrated by Roman soldiers, some of whom were of Germanic origin. The peregrines are far less represented and very few bear Celtic names.

On account of her name and of her devotees, Coventina’s Celtic character is therefore questionable. Given the various votive offerings discovered in the well, it remains clear, however, that she was a goddess presiding over the springs of this locality. Allason-Jones, referring to two inscriptions unearthed in Spain, in Os Curvenos2001 and Santa Cruz de Loyo,2002 and a dedication discovered in France, in Narbonne (Aude),2003 believes that Coventina was worshipped on a larger scale.2004 However, it must be borne in mind that those inscriptions are obscure and the relation with British Coventina doubtful.