3) Stanna / Sianna (?)

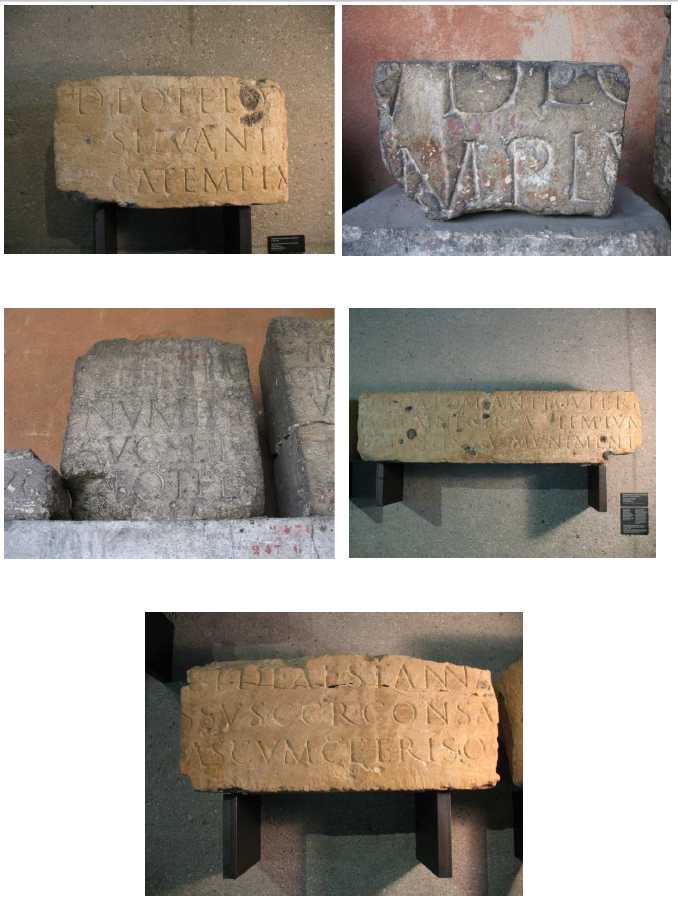

The goddess Stanna is attested by an inscription composed of five fragments discovered in the buildings of the ‘Vieilles Casernes’ in Périgueux (Dordogne), in the territory of the Petrocorii, where she is partnered with the god Telo (fig. 48). Thanks to the comparison of the various fragments, the suggested restoration is certain, except for the end of the first line and the beginning of the second line: Deo Telo et deae Stannae, solo A(uli) Pomp(eii) Antiqui, Per…ius, Silvani fil(ius) Bassus, c(urator) c(ivium) r(omanorum), consaeptum omne circa templum et basilicas duas, cum ceteris ornamentis ac munimentis, dat, ‘To the god Telo and to the goddess Stanna, Per[…]ius Bassus, son of Silvanus, curator of the Roman citizens, offers, at his own expense, this entire wall erected around their temple on the land of Aulus Pompeius Antiquus, and these two basilicas with the other embellishments and accessories’.2086 This inscription is of great interest, for it mentions the existence of a temple dedicated to Telo and Stanna. The dedicator Per[…]rius Bassus is a Roman citizen and holds official functions. He is a curator, which means he had been appointed by the emperor to manage and supervise the finances of the city. He offers a wall, two basilicas, ornaments and accessories extending and embellishing the sanctuary, which is built on the property of the Roman citizen Aulus Pompeius Antiquus. This wall and basilicas may correspond to the Gallo-Roman remains excavated in the surroundings of the ‘Tour de Vésone’, which was the temple dedicated to Tutella Vesunna, the eponymous goddess of the city (see Chapter 3).2087 The re-use* of the stone does not allow us to identify the origin of the inscription. The archaeological context and the possible functions of Telo and Stanna in Périgueux remain thus undeterminable.

The god Telo is known from another inscription discovered in Périgueux.2088Telo and Stanna seem thus to be topical* or local deities. Telo’s name nowadays survives in the name of a village situated 3 kms from Périgueux, called Le Toulon, which takes its name from a nearby spring gushing forth from an abyss. This spring was anciently named ‘Fountaine de Toulon’ and is known today as ‘Fontaine du Cluseau’ or ‘Fontaine de l’Abîme’.2089 Telo must have been originally a deity presiding over water. This is probably the reason why rivers and towns situated near a stream or a spring bear that name. According to Paul Aebischer, rivers and places named Toulon or Touron are derived from the same root as the name of the god. Those names are quite common in the toponymy* of the south of Gaul, from the Var to the Landes and from the Aude to the Périgord, where they are particularly numerous. In Dordogne, thirty-one springs, streams and places called Touron are recorded, such as the spring of the Touron, which gushes forth from a rock near the village of Font-Roquesuch, the spring of the Touron, in Saint-Sulpice-d’Eymet, and the fountain of the Touron in the village of Rouffignac.2090 In the area of Le Thonolet and Martigues (Bouches-du-Rhône), Bargème and Callians (Var) and Grasse (Alpes-Maritimes), many rivers, fountains and springs are called Touloun, Touroun, Touron, e.g. the spring of Thoulon in Martigues; the stream Toulon, a tributary of the River Touloubre in the département of the Bouches-du-Rhône; and the stream Toulou, a tributary of the River Braune in the département of Gard.2091

The meaning of Stanna’s name remains obscure. Anwyl proposes to relate it to a root sta- meaning ‘to stand’; hence Stanna, ‘the Standing or Abiding one’.2092 There is a Gaulish root sto-, derived from the IE *-sth2-o-, signifying ‘who stands’, but Delamarre does not seem to believe that Stanna is etymologically related.2093 As for Marie Durand-Lefebvre, she assumes that stanna is cognate with the Anglo-Saxon stan, Dutch steen, Icelandic stein, Danish and Swedish stenn, German stein, Gothic stains, Russian stiena and Greek στια or στιον, i.e. ‘the rock’.2094 Stanna would thus refer to the rock where the spring emanates and would have originally been the goddess embodying the mountain. Unlike the name of her partner, Stanna does not survive in the local idiom.2095 Her association with the water-god Telo in Périgueux, however, would indicate that she was a spring-goddess.

As regards the dedication engraved on an altar in white marble discovered in 1824 in the middle of the ruins of the Gallo-Roman baths excavated on the Mont-Dore (Puy-de-Dôme), in the territory of the Arverni, it is difficult to determine whether this stone is dedicated to the god Siannus or to the goddess Sianna, for the end of the name is missing. The inscription reads: Julia Severa Siann[ae] / Siann[us] v(otum) s(olvit) l(ibens) m(erito), ‘To Sianna or Siannus, Julia Severa paid her vow willingly and deservedly’ (fig. 49).2096 The dedicator is a woman, who bears Latin names and the duo nomina of Roman citizens. She thanks the deity for accomplishing a vow she had previously made. Because the inscription begins with the name of the dedicator, which was particularly in use in the 1st c. AD, the inscription must date from this time.2097 Most of the scholars, such as Jullian, Renel, Holder, Jüfer, Olmsted and Delamarre, are inclined to think that this inscription is dedicated to Siannus, because this god is known from another inscription discovered in Lyons (Rhône),2098 where he is linked to Apollo, who replaced many native healing water gods in Gallo-Roman times.2099 As the inscription was unearthed on the site of an ancient thermal establishment, it is likely that the healing god Siannus presided over the salutary springs of Mont-Dore. And yet, Vaillat and Rémy point out that the inscription was certainly dedicated to a goddess, since the sculpture of a draped and standing woman, holding an unidentified object in her left hand, was originally represented in bas-relief* right above the inscription.2100 Sianna may in fact be a variant of Stanna and refer to the same goddess, for the letters I and T, being very similar in shape, can be easily confused.2101 Before the last inscription was discovered, the goddess Bricta/Brixta in Luxeuil was for instance miscalled Bricia or Brixia, because the T was misread as an I.2102 Moreover, Périgueux is situated about 200 kms from Mont-Dore, which is not far away. Contrary to what Vaillat maintains, it is thus highly likely that Sianna and Stanna are the very same divine figure.2103

Sianna might have been the goddess protecting the waters of Mont-Dore, which were known and used in Gallo-Roman times, as proven by excavations carried out on the site in 1825. When Michel Bertrand started to build a thermal establishment in 1817, he discovered the remains of huge Gallo-Roman baths, preceded by a yard surrounded by columns and composed of two spacious galleries and rooms, where the baths and swimming-pools were supplied with the waters of several hot springs, harnessed by lead pipes.2104 A rectangular temple with six columns, known as a ‘Pantheon’, composed of a first portico giving access to a cella* followed by a smaller portico, was also discovered.2105 The remains of decorations and ornaments testify that it was a religious edifice, very certainly erected in honour of the deity of the place.

The worship of the salutary waters of Mont-Dore may go back to Celtic times, for a very well-preserved quadrangular swimming-pool (4m long and 1.50m deep), made of fir-tree trunks - the bark of which had been stripped off - was excavated under the Gallo-Roman building and a thick layer of hard rock.2106 The archaeologists also found a fir-tree trunk (15cm thick and 5m long), hollowed out in the middle, harnessing the thermo-mineral spring called ‘Boyer’ to the wooden swimming-pool, which could contain up to fifteen people.2107 No other archaeological data have provided evidence of the cult of the goddess Sianna, apart from a lost sculpted socle which had a woman with a vestal costume surrounded by seven genii. Durand-Lefebvre suggests that the woman could be the representation of the main spring, and the seven genii the embodiment of the seven secondary springs. 2108 The genii are indeed often associated with mother goddesses and water on iconographical devices, but this theory remains conjectural.2109

On account of her association with the god Telo, who was certainly attached to water, and the inscription to Sianna discovered in the Gallo-Roman thermal building of Mont-Dore, it can be suggested that Stanna/Sianna was a goddess presiding over salutary waters in south-central Gaul in ancient times.