b) Inscriptions

Until the end of the 18th c., Luxovius and Bricta were known only by a lost inscription, reproduced in an 8th- or 9th-century manuscript of the Abbey of Luxeuil, entitled Homilia SS. Patrum in Evangelia quattuor.2126 This inscription was discovered again together with a second dedication, coins and potteries, during excavations carried out in 1777 around the present-day yard of the thermal establishment. The stone was not linked at once to the inscription mentioned in the manuscript, which is why they used to be understood as two different inscriptions. The now lost dedication, probably dating from the 3rd c. AD, reads: Luxovio et Brixtae C(aius) Jul(ius) Firmanius v(otum) s(olvit) l(ibens) m(erito), ‘To Luxovius and Brixta, Caius Julius Firmanius paid his vow willingly and deservedly’.2127 The dedicator is a Roman citizen, for he bears the tria nomina. The votive formula v.s.l.m. indicates he is grateful to the divine couple for granting his vow.

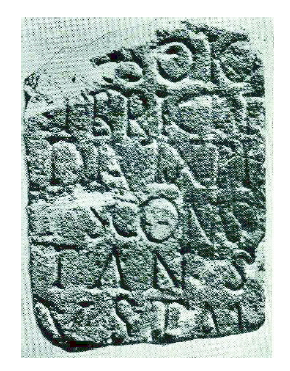

The second inscription, now housed in the ‘Château de Filain’, is the following: [Lus]soio et Brictae, Divixtius Constans, v(otum) s(olvit) l(ibens) m(erito), ‘To Luxovius and to Bricta, Divixtius Constans paid his vow willingly and deservedly’ (fig. 50).2128 The dedicator bears the duo nomina of Roman citizens, but his gentilice* Divixtius is a typical Celtic name, based on divic-, ‘to avenge’.2129 In keeping a Celtic name, the dedicator shows that, despite his Romanization, he remains attached to his indigenous origins. In this inscription, the name of the god is spelt Lussoius instead of Luxovius, which is not surprising, as the letters x and ss were interchangeable in the Roman epigraphy.2130

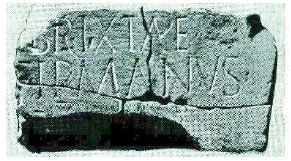

The last stone inscription, probably dating to the 1st c. AD, composed of four fragments, was fortuitously found in 1938 during earthworks undertaken to the west of the thermal establishment, where it can be seen nowadays. It reads: Brixtae Firmanus [v(otum) s(olvit) l(ibens)] m(erito), ‘To Brixta, Firmanus paid his vow willingly and deservedly’ (fig. 51).2131 The dedicator Firmanus is certainly the same person who dedicated the first inscription. He may thus have been a pilgrim returning to the water sanctuary at Luxovium.

It should be pointed out that the inscription mentioning a temple erected in honour of the goddess Brixia in the reign of Caesar Augustus and the consulate of Tiberius and Cneius Calpurnius Pison, found in 1781 near the Roman baths, is an ‘inscription falsae’, that is a fake inscription made by a forger: Divæ auxiliari Brixiæ, regnante Cæsare Augusto, consulibus Tiberio et Pisone dedicatum templum.2132 It was discovered with a statue of a ‘Cavalier à l’anguipède’ type, representing a Gaulish Jupiter holding a cart-wheel in his left hand and riding a horse trampling on a human head.2133 The meaning of this representation is still obscure, but it definitively has a connection to the worship of water and the sun.2134