c) Thermal baths and Votive offerings

The ancient name of Luxeuil-les-Bains is neither mentioned in the Classical texts nor in the 4th-century Carte de Peutinger, but in The Life of Saint Columbanus, written in the 7th c. by the Italian monk Jonas de Bobbio who describes the foundation of the monastery of Luxeuil (Luxovium) by Saint Colombanus around 590.2135 He refers briefly to the worship of the hot springs by the local pagan people, who offered ex-votos in stone to the deities of the place and performed rites and ceremonies in the nearby wood:

‘Cum iam multorum monachorum societate densaretur, coepit cogitare, ut potioris loci in eodem heremo quereret, quo monasterium construxisset, invenitque castrum firmissimo munimine olim fuisse cultum, a supradicto loco distans plus minus octo millibus, quem prisca tempora Luxovium nuncupabant: ibique aquae calidae cultu eximio constructae habebantur. Ibi imaginum lapidearum densitas vicina saltus densabat, quas cultu miserabili rituque profano vetusta paganorum tempora honorabant, quibusque execrabiles ceremonias litabant; solae ibi ferae ac bestiae, ursorum, bubalorum, luporum multitudo frequentabant.2136As he was already hemmed in by the presence of many monks, he began to consider whether he might discover a suitable place in the same wilderness where he might found a monastery, and he discovered a fortress which had once been protected by the strongest of fortifications, approximately eight miles from the aforementioned place. Earlier times had called it Luxovium. There hot baths [lit. waters] had been built with considerable care; there a large number of stone images filled the neighbouring woodland: these, ancient pagan times had honoured with miserable ritual and profane rites, and for them they performed execrable ceremonies; the place was frequented only by wild animals and beasts, a multitude of bears, wolves and buffalo.2137 ’

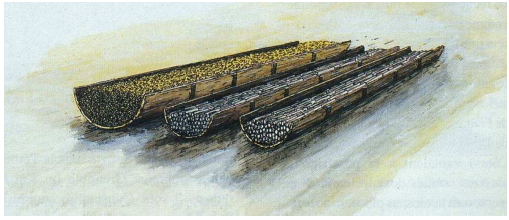

This description is significant, for it coincides with the discovery of the stone inscriptions dedicated to Luxovius and Bricta and the Gallo-Roman thermal establishment, excavated from 1775 to 1785, and from 1857 to 1858.2138 The Gallo-Roman building, situated on the site of the present baths, was composed of more than five vaulted rooms, cobbled with alabaster and adorned with mosaics, containing baths, basins and surrounded by galleries with porticos. A network of piping, including aqueducts in stone and hollowed oak trunks serving as channels for harnessing the spring water inside the establishment, was also discovered. Nearby the ferruginous springs, Félix Bourquelot unearthed remains of columns, which could indicate proof of the existence of a small temple dedicated to Luxovius and Bricta in this area.2139 It is besides interesting to note that, in the 19th c., the ferruginous springs were called ‘Springs of the Temple’.

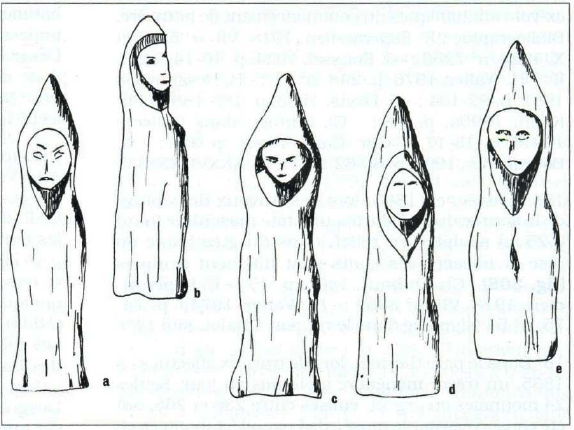

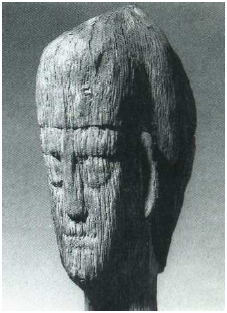

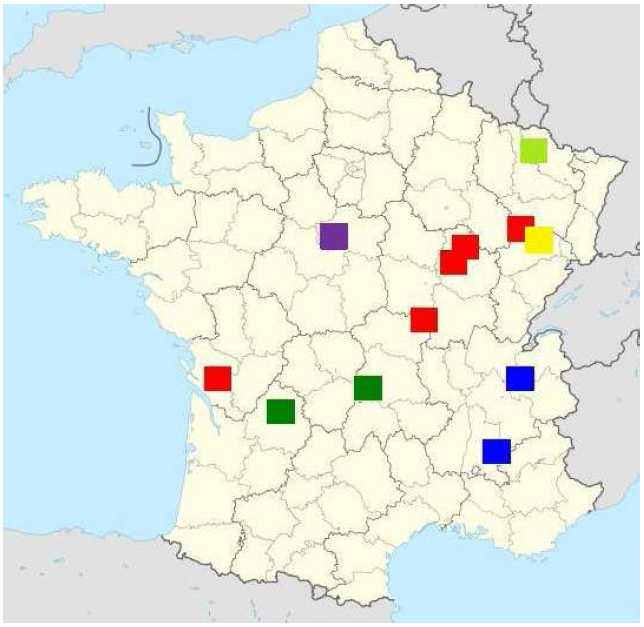

In addition to Luxovius and Bricta, Apollo and Sirona, the renowned divine couple of healing springs, were also honoured in Luxeuil, since an inscription dedicated to them engraved on an altar in white marble sculpted on three sides comes from the site.2140 Various votive offerings evidencing the worship of protective deities of the local springs have been discovered. In 1932, three wooden kegs containing about 20,000 coins in copper and silver, dating from 320 AD to 335 AD, were unearthed (fig. 52).2141 In 1865, a hundred statues in oak, representing rough heads, busts and full-scale characters, and an anatomic ex-voto* in the shape of a leg, were discovered in a layer of black earth at the spring of the ‘Pré-Martin’, situated 150 metres north of the thermal establishment.2142 Except for nine of them, the rest crumbled into dust on contact with air when they were discovered.2143 Despite the roughness and distortion of the statues, it is noticeable that some of the characters wear the bardocucullus* and the Celtic torque* around their neck (fig. 53 and 54). Those statues probably date from the end of the 1st c. BC or the beginning of the 1st c. AD, for a coin from the time of Augustus was found in the same layer of earth.2144 These votive offerings are similar to those found at the ‘Fontaine Segrain’ in Monthay-en-Auxois (Côte d’Or), at the sanctuary of the Sources-de-la-Seine (Côte d’Or), Essarois (Côte d’Or), Bourbonnes-les-Bains (Haute-Marne), Saint-Honoré-les-Bains (Nièvre), Saint-Amand-les-Eaux (Nord), Montbouy (Loiret), Chamalières (Puy-de-Dôme), etc.2145 They attest of a cult rendered to curative water deities. They indeed represent the pilgrims who came to the sanctuary of Luxeuil-les-Bains to soothe their pains in taking the salutary waters and praying to the healing deities: Bricta and Luxovius. The ex-votos were offered to earn divine benevolence, to obtain the recovery of a sick person or to express one’s gratitude after being granted a vow.