b) Inscriptions and Places of worship

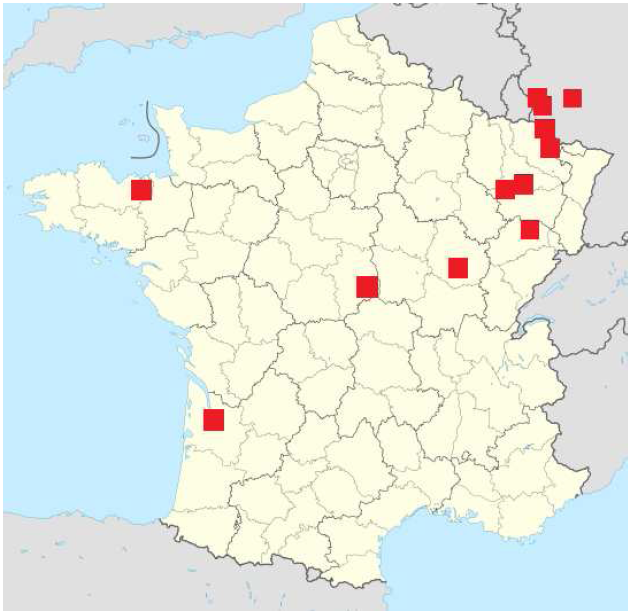

Sirona was particularly worshipped in the north-east of Gaul, as inscriptions discovered in the départements of Moselle (1), Meurthe-et-Moselle (1), Vosges (1), Haute-Saône (1) and Côte d’Or (1) illustrate. Dedications to her have also been discovered in Germany, in the territory of the Treveri, notably in Trier (1), Mainz (1), Bitburg (1), Nietaltdorf (1) and Hochscheid (1), where a shrine linked to a spring was excavated. Her cult was probably extended to the whole of Gaul, since a dedication comes from the département of Cher, in the centre of Gaul, another from Côtes d’Armor, in the north-west of Gaul, and a last one from Gironde, in the south-west of Gaul.

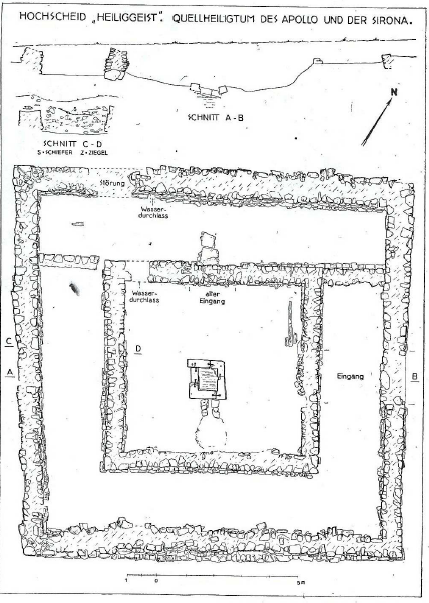

In the Treveran territory, the close relationship between Sirona and curative waters stands out. In Bitburg, a dedication in two fragments reading In h(onorem) d(omus) d(ivinae) Apollin[i Granno] et Siro[nae], ‘In Honour of the Divine House, to Apollo Grannus and Sirona’, was discovered in 1824 near a perennial spring.2160 The formula in h.d.d. indicates the inscription is from the 3rd c. AD.2161 The most significant example is the water sanctuary of Hochscheid, where representations of Apollo and Sirona and dedications to them were discovered. Hochscheid is situated between Mainz and Trier, where an inscription was also found: D(e)ae Sirona[e] L(ucius) Lugnius, ‘To the goddess Sirona Lucius Lugnius’.2162 The dedicator is a Roman citizen, for he bears the duo nomina, but his cognomen* Lugnius is Celtic: it seems to be based on lugu-, found in the name of the Celtic god Lugus.2163 The shrine at Hochscheid, probably dating from the 2nd c. AD, was composed of a portico surrounding a square cella*, where the waters of the nearby spring were collected in a small central basin (fig. 56).2164 The temple was apparently built over an enclosure in wood predating Roman times.2165 The inscription to the divine couple is engraved on an altar: Deo Apollini et Sancte Sirone R. C. Pro Con[…], ‘To the god Apollo and to Sacred Sirona R. C. Pro con (?) […]’.2166 In the sanctuary were discovered various votive terracotta figurines picturing an Apollo with a lyre, a Silvanus, a Minerva, a Venus, a Diana, a Fortuna with a patera*, and seated single mother goddesses with a diadem, a baby or an animal.2167 A statue of Classical type, representing a standing goddess wearing a dress and a diadem and holding a patera* in her left hand, was also unearthed (fig. 57).2168 The snake curled around her right forearm relates her to the bronze group from Mâlain: Sirona is depicted with the features of Hygeia, the Roman goddess of healing. The water sanctuary and the representation of the goddess clearly prove that Apollo and Sirona were associated with the spring gushing forth near the shrine and its possible curative virtues.

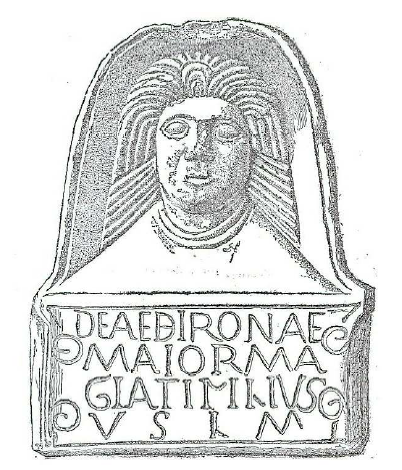

In the territory of the Mediomatrici, an inscription to Sirona, probably dating from the 2nd c. AD, engraved under a schematized representation of the goddess, was discovered in 1751 on the bank of a pond in Sainte-Fontaine, near Saint-Avold (Moselle), where a sacred spring used to flow (fig. 58).2169 The stele* was destroyed in the 1870 fire at Strasbourg Library, but casts are housed in the museums of Metz, Nancy, Epinal, Saint-Germain-en-Laye and Orléans. The dedication is the following: Deae Đironae Maior Magiati filius v.s.l.m., ‘To the goddess Sirona Maior son of Magiatus paid his vow willingly and deservedly’.2170 The dedicator and his father are peregrines bearing Celtic names. Maior may be based on the same root magio-, ‘big’ as his father’s name Magiatus – but Maior can be envisaged as a Latin name too.2171 The goddess is pictured with bulging eyes and wears her hair loose in Egyptian style. The two circles around her neck may represent a necklace or the collar of her dress.2172 The seventeen fragments of lapidary monuments and dedications unearthed in the area - such as the statue of a naked man; a head of a young beardless man; an inscription to the god Apollo; and a headless and footless statue of a draped goddess holding a snake in her left hand, possibly representing Hygeia or Sirona - may indicate evidence of a place of devotion to Sirona and Apollo. However, the foundations of a potential temple dedicated to the divine couple have never been excavated.2173

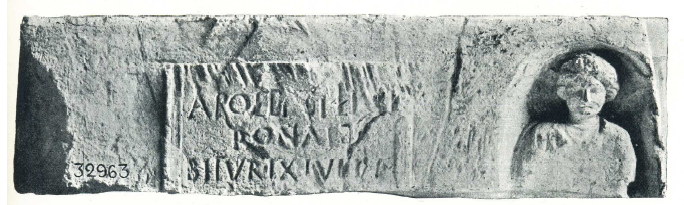

In the territory of the Leuci, a 2nd-century inscription, engraved on a stele* broken on the left, dedicated to Sirona and Apollo was discovered in 1823 at a place known as ‘La Fontaine des Romains’, 300 metres to the south-east of the village of Tranqueville-Graux (Vosges). It reads: Apollini et Sironae Biturix Iulli f(ilius) d(onavit), ‘To Apollo and Sirona, Biturix, son of Jullus offered (this altar)’.2174 The dedicator and his father are peregrines and bear Gaulish names. Iullus is known from an inscription discovered in Reims,2175 while Biturix, composed of bitu-, ‘world’ and rix, ‘king’, is a typical Celtic name meaning ‘King of the World’.2176 On the right hand-side of the inscription, a bust of Sirona appears in a niche (fig. 59). Her representation is classical - she wears a dress and her hair is done into a bun. The bust of Apollo must have originally been carved in another niche, the remains of which appear on the left-hand side of the inscription. Together with the stele* was unearthed a ten-metre basin containing a large amount of Roman coins and a fragment of sculpture representing seven heads, possibly symbolizing the seven days of the week.2177 In view of those discoveries, it is clear that Sirona and Apollo presided over the waters of a fountain which used to flow in this basin. The name of the place ‘La Fontaine des Romains’ is beside indicative of a spring worshipped in Gallo-Roman times.

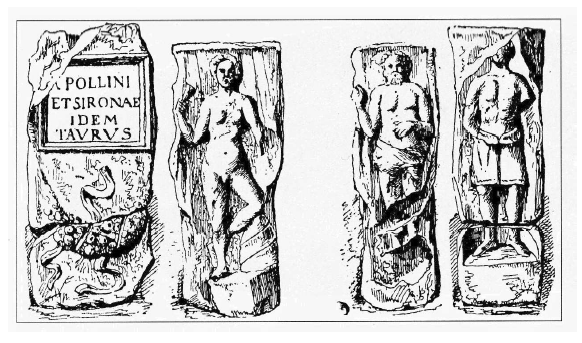

In the territory of the Sequani, a dedication to Apollo and Sirona engraved on an altar in two fragments was unearthed in 1858 in the garden of the thermal establishment at Luxeuil (Haute-Saône), the healing waters of which were presided over by Luxovius and Bricta in Gallo-Roman times: Apollini et Sironae idem Taurus, ‘To Apollo and Sirona, Taurus the same’ (fig. 60).2178 The dedicator is a peregrine* bearing a Latin name; he is thus in the process of Romanization. The word idem at the end of the inscription indicates that Taurus had already previously made an offering to the gods. Emile Espérandieu and Charles Robert argue that the relief* carved under the inscription is not a snake but a wreath entwined with a ribbon, called a lemniscus*.2179 On the back panel can be seen a representation of Apollo standing naked, possibly holding a plectrum*, with a lyre at his feet, while the lateral panels contain carvings of two gods, both bare-chested; one bearded and one clean-shaven.

In the territory of the Lingones, a bronze group representing a half-naked goddess holding a snake in her right hand and a naked god holding a plectrum* in his right hand and the remains of a three-stringed cithara* in his left hand was discovered in 1977 in a hiding place, built around 280 AD, situated in an out-building adjoining a house, at a place known as ‘Champ Marlot’, in Mâlain (Côte d’Or), 300 metres to the west of a temple excavated in 1969 by Louis Roussel.2180 It was found together with seven other bronze statues, representing a winged Victory, a young Bacchus, a standing Mercury, a lunar deity, a seated Fortuna and a group of Juno and the Genius. On the socle of the bronze group is engraved an inscription which identifies the couple as Apollo and Sirona: THIRONEAPOLLO, ‘Sirona (and) Apollo’ (fig. 61).2181 On account of the snake she holds in her hand, Sirona can be compared to Hygeia, the Roman goddess of health and hygiene, whose main attribute was the snake.2182 Deyts nonetheless points out that Hygeia is never pictured half-naked in the Roman iconography.2183

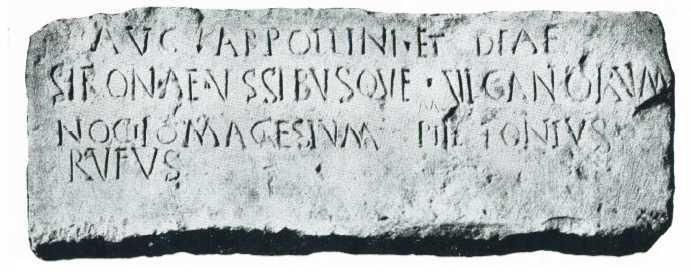

In the centre of Gaul, in the territory of the Bituriges Cubi, a 2nd-century inscription, honouring Sirona and Apollo, was discovered in 1954 in the wall of a house located at a place known as the ‘Hameau des Bertrands’, in Flavigny (Cher).2184The dedication reads: Aug(usto) Apollini et deae Sironae ussibusque vicanorum Nogiiomagie(n)suim M. Piieionius Rufus, ‘To the August Apollo and to the goddess Sirona, for the benefit of the inhabitants of the vicus* of Negeomagus, M. Pieionius Rufus reverently (erected) this monument’ (fig. 62).2185 The dedicator, who bears the tria nomina of Roman citizens, offered an edifice in honour of the divine couple and for the usage of the inhabitants of a vicus*, the site of which remains undetermined.2186Paul Cravayat, who studied the dedication in 1955, assumed that the worship of Apollo and Sirona was linked to a neighbouring fountain. After investigating the area, he discovered two springs, called ‘Grivin’ and ‘Monconsou’, respectively emanating 1,200 metres and 700 metres to the north of the hamlet.2187 Interestingly, the waters of those springs have some thermal virtues and continue to flow profusely. Moreover, fragments of pottery, Roman coins and stone seats, possibly dating from Gallo-Roman times, were discovered in the 19th c. in the fountain of ‘Monconsou’, which could indicate evidence of a cult devoted to the spring.2188 In 1882, remains of foundations of a building and architectural fragments, notably comprising a piece of a capital, a drum of a column and a hand of a statue, were unearthed about a hundred metres to the north-west of Flavigny.2189 Those remains might have belonged to a religious edifice. Even though those various discoveries are of interest, there is no tangible proof of a temple erected for Apollo and Sirona in the area. Indeed, there is no clear evidence of any kind confirming their worship at the spring of ‘Monconsou’ or ‘Grivin’.

In the north-west of Gaul, in Corseul (Côtes-d’Armor), the county town of the civitas* of the tribe of the Coriosolites created by Augustus, an inscription dedicated to the goddess Sirona was discovered in 1834 in re-employment* in the chapel of the Castle of Montafilan: Num(ini) Aug(usti) De(ae) Đirona(e) Cani(a) Magiusa lib(erta) v.s.l.m., ‘To the divine power of Augustus and to the goddess Sirona, Cania Magiusa freed. She paid her vow willingly and deservedly’.2190 The use of the formula dea indicates that the dedication is not prior to the mid-2nd c. AD. The dedicator is a woman and a freed slave, who bears Celtic names: Cania is based on Gaulish cani-, probably meaning ‘good’, ‘beautiful’, and Magiusa derives from magio-, ‘big’, ‘field’.2191 Because of the re-employment* of the stone, it is impossible to determine its origin and, thus, in which context Sirona was worshipped.

In the south-west of Gaul, in Bordeaux (Gironde), an inscription engraved on an altar in hard stone, probably dating from the beginning of the 1st c. AD, discovered in 1756 in re-employment* in the foundations of a hotel, reads: Sironae Adbucietus Toceti fil(ius) v(otum) s(olvit) l(ibens) m(erito), ‘To Sirona, Abducietus, son of Tocetus, paid his vow willingly and deservedly’.2192 The devotee Adbucietus and his father Tocetus are peregrines bearing Celtic names – Tocetus might come from tucca, tucetta, ‘bottom’ or togi-, ‘oath’.2193 Another altar found in Bordeaux, carved on four panels, might be dedicated to Sirona. Nevertheless, as the beginning of the inscription is unreadable, the name of the goddess ending in [...]onae could be dedicated to Divona, whose fountain in Bordeaux was famous in antiquity.2194

From this, it follows that the Celtic goddess Sirona was particularly worshipped in the north-east of Gaul, notably in the Treveran territory, but not confined to it, as the inscriptions from Flavigny (Cher), Corseul (Côte d’Armor) and Bordeaux (Gironde) show (fig. 63). Being partnered with Apollo (Grannus), the god of healing springs, and being revered in connection with curative waters - such as in Luxeuil (Haute-Saône) – or with springs and fountains - such as in Bitburg (Germany), Hochscheid (Germany), Saint-Avold (Moselle), Tranqueville-Graux (Vosges) and possibly Flavigny (Cher) - Sirona appears as a goddess presiding over waters in general - waters with or without curative properties. Outside Gaul, Sirona also protects salutary waters, such as in Nierstein (Germany), where a dedication to her and Apollo was discovered near sulphur springs;2195 and in Wiesbaden (Germany), where an inscription, mentioning the offering of a temple by a Roman curator, was unearthed in the ruins of the Roman thermal establishment.2196 It is interesting to note that in Gaul, she is mostly worshipped by people of Celtic stock. This is significant, for it proves that her cult pre-dated the Roman conquest and that it was still extant among the local population in Gallo-Roman times. Most of them are peregrines bearing Gaulish names, such as Biturix, son of Iullus, in Tranqueville-Graux, Abducietus, son of Tocetus, in Bordeaux and Maior, son of Magiatus, in Saint-Avold. In Luxeuil, Taurus bears a Latin name but is a peregrine*. By invoking a Celtic goddess, he shows that, despite his Romanization, he is still attached to his original cults. Others, such Cania Magiusa in Corseul and Lucius Lugnius in Trier, are Roman citizens who have Celtic names. This proves their desire to display their attachment to their indigenous origins and their profound respect for their ancient deities, whom they continued to honour and to pray to in spite of their Roman citizenship.