4) ‘Intoxicating’ Containers: Yew and the Eburnicae

Finally, intoxication could be reached through the absorption of decoctions, that is infusions of plants, or of fermented drinks - various plants or honey being left to macerate and ferment in some liquid. Before going into more details about sacred beverages, it is worth noting that the nature of the container, in which the drink was left to macerate, must have played a very important role in the composition and preparation of the drink itself, for it must have added some other intoxicating or visionary properties to it.

According to Matthieu Poux, more than 90 % of the wooden buckets used for the mix of the alcoholic beverages were made of yew (taxus baccata).2273 And it is noteworthy that buckets made of yew were excavated either in tombs or in ‘offering wells’ (sometimes 10-metre deep) on sacred Gaulish sites, such as the two yew buckets, probably dating from the end of the 2ndc. BC, discovered on the plateau of the Ermitage (Gaulish oppidum* of the Nitiobroges), in Agen; and the bucket, dating from the 2nd or 1st c. BC, which was part of a wine service, excaveted on the site of Vieux-Toulouse (territory of the Tolosates).2274 Modern scholars agree that the votive deposits in ‘offering wells’ are the reflection of ancient magic-religious rites in honour of the gods.2275 Consequently, it is clear that the yew buckets discovered in sacred places contained sacred intoxicating beverages. As the choice of oak wood in the making of votive statues dedicated to water-goddesses was certainly not done by chance, the use of the yew in the making of bucket containing sacred liquids is certainly not insignificant.

Yew was known in ancient times for its healing powers as well as for its dangerous psychotropic and poisoning properties, and thus played an important role in various magic-socio-religious rites and medicine of the time.2276 The toxicity of the yew was known from the Celts, for Caesar reported that the chief of the Eburones, called Catuvolcus, poisoned himself with yew, preferring death to surrender to the Romans.2277 Pliny also alludes to the fact that its toxic sap was used in the making of specific ointments applied at the end of the spears or arrows of the Celtic warriors to create lethal weapons, like they did with datura stramonium.2278

As regards the buckets, the yew was used on account of its solidity, longevity, and imputrescibility, which allowed for the preserving of liquids. Beyond the technical approach, it is also possible that yew, the psychoactive effects of which are mentioned in the classical texts and attested by recent research, played a part in the making of some divine beverages.2279 If a beverage is made to ferment in a bucket of yew, it is, scientifically speaking, quite possible that the visionary properties of the wood are released in the drink. This possibility is attested by Pliny who denounced the specific intoxicating effects of wine preserved in barrels made of yew:

‘Similis his etiamnunc aspectu est, ne quid praetereatur, taxus minime virens gracilisque et tristis ac dira, nullo suco, ex omnibus sola bacifera. mas noxio fructu; letale quippe bacis in Hispania praecipue venenum inest, vasa etiam viatoria ex ea vinis in Gallia facta mortifera fuisse compertum est.2280Not to omit any one of them, the yew is similar to these other trees in general appearance. It is of a colour, however, but slightly approaching to green, and of a slender form; of sombre and ominous aspect, and quite destitute of juice: it is the only one, too, among them all, that bears a berry. In the male tree the fruit is injurious; indeed, in Spain more particularly, the berries contain a deadly poison. It is an ascertained fact that travellers’ vessels, made in Gaul of this wood, for the purpose of holding wine, have caused the death of those who used them.2281 ’

Marguerite Gagneux-Granade explains that the lethal alkaloid of the tree would have had a limited effect on a beverage contained in a yew bucket, given that it was made of cut-down wood.2282 Therefore, it can be suggested that an intoxicating beverage (mead, beer, wine), prepared for a religious occasion, is highly likely to have been left macerate in a yew bucket on purpose, for it to become infused with the psychotropic substances contained in the wood.

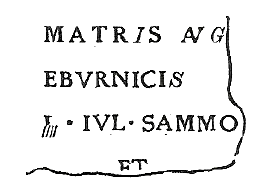

Interestingly, an inscription, engraved on a Gallo-Roman altar, discovered in Yvours-sur-le-Rhône, near Lyons (Rhône), in the territory of the Segusiavi, is dedicated to the Matres Eburnicae (‘Mother Goddesses of the Yew’): Matris Aug(ustis) Eburnicis Jul(ius) Sammo[…] et […], ‘To the August Mother Goddesses Eburnicae, Julius Sammo[…] and […]’ (fig. 6).2283 The first dedicator has Latin names and is a Roman citizen, for he bears the duo nomina.

Their name is based on Gaulish eburos signifying ‘yew’, similar to Old Irish ibar, ‘yew’, Breton evor and Welsh efwr, ‘alder buckthorn’.2284 The Celtic word is found in names of Celtic tribes, such as the Eburouices (‘Combatants of the Yew’)2285 or the Eburones (‘People of the Yew’)2286 in Gaul, and the Eόganacht (‘People of the Yew-Tree’) in Munster, Ireland,2287 and in toponyms*, such as Eburo-briga (‘Hill of the Yew’) - modern Avrolles (Yonnes, France) - and Eburo-dunum (‘Fort of the Yew’) - modern Yverdon (Switzerland). It is besides interesting to note that there may be a homonymy between the place-name Yvours (*Eburnicum, ‘Place planted with Yew Trees’?) and the divine epithet Eburnicae. Finally, the word is also found in proper names, such as in the Irish mythical name Eógan, which derives from a Celtic Iwo-genos, literally meaning ‘yew-conception’, ‘conceived by the yew-tree’ or ‘born of the yew’ (éo is ‘yew’) indicates a divine filiation.2288

Olmsted considers these mother goddesses to be simple protective mothers venerated by the Eburones, and justifies the location of the inscription (Lyons) by the mobility of local peoples in Gallo-Roman times.2289 There may be an alternative explanation, for these mothers were certainly the very personification of the yew tree, which was highly revered by the Celts and used in war, social and religious contexts.2290 They must also have embodied the powerful intoxicating properties of the tree, as its wood was used in the making of ritual buckets, which were part of religious rites of intoxication in order to make contact with the divine. From all of this, it follows that the Matres Eburnicae could have had the functions of Intoxicating Goddesses.