3) Inscriptions from the Continent

a) The Comedovae (Matrae, Dominae)

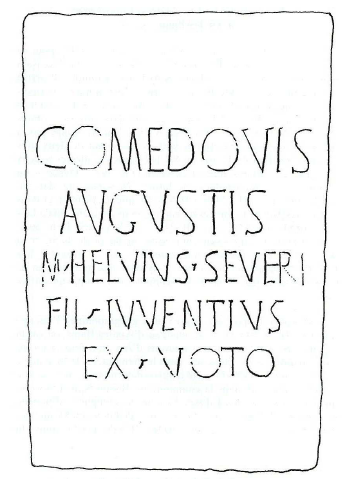

An inscription, dedicated to the Comedovae, was discovered in Aix-les-Bains (Savoy) - the date and place of discovery are unknown. In the 16th c., Alphonse Delnène, a local historian, pointed out that the inscription was embedded in the wall situated to the right of the castle - which is today the town hall -, not very far away from the Gallo-Roman ‘Temple de Diane’, probably originally dedicated to an indigenous healing deity presiding over the curative waters of Aix-les-Bains, that is Borvo or the Comedovae.2339 In 1838, the inscription was brought to the property of the Marquis d’Aix-les-Bains in Sommariva, located in Piémont (Italy). The stone, lost for a long time, was rediscovered a few years ago by Giovanni Mennella in Sommariva Bosco, where it was embedded in one of the outside walls of the castle.2340 The inscription is the following: Comedovis Augustis M(arcus) Helvius Severi fil(ius) Iuventius ex voto, ‘To the August Comedovae, Marcus Helvius Iuventius, son of Severus, in accordance with a vow’ (fig. 8). The dedicator has Latin names and bears the tria nomina of Roman citizens.

Various etymologies have been proposed for the theonym Comedovae. Rémy and De Vries have argued that their name is based on a theme *med- which can mean ‘to judge’, ‘to think about’ or ‘to recover (health)’.2341 Accordingly, the Comedovae may have been healing water-goddesses presiding over the thermal spring of Aix-les-Bains. Delamarre and Olmsted have suggested that it is a compound *co-medovis, composed of the Celtic suffix co meaning ‘with’, ‘together’ or ‘similar’ and of the Celtic root *medu, ‘mead’.2342 The suffix co probably emphasizes the fact that these mother goddesses were envisaged as similar figures, deeply interrelated in their function of intoxicating, which tends to increase the image of their power. The Comedovae could therefore mean ‘the Ones who all together intoxicate by means of mead’. Finally, Lambert, who disagrees with Delamarre’s etymology, has demonstrated that the divine name Comedovae (*kom-med-wōs) is based on the theme *med- meaning ‘to govern’ or ‘to command’.2343 According to him, the Comedovae may be ‘the Ones who Rule’, that is the ‘Sovereign’. As explained above, these last two etymologies are acceptable, since *med- and *medu- are derived from two homonymic roots, respectively referring to intoxication and sovereignty; notions which were interrelated.

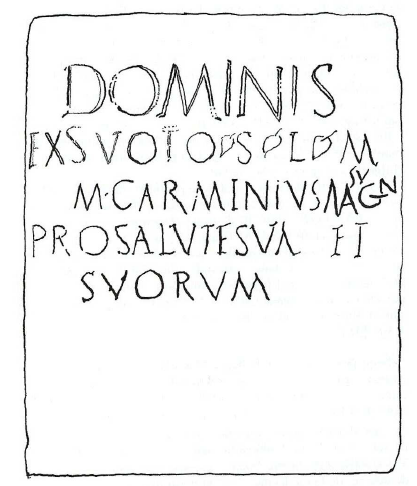

The Comedovae can be linked to the other two inscriptions discovered in Brison-Saint-Innocent - a village next to Aix-les-Bains -, honouring the Dominae and the Matrae. The inscription dedicated to the Dominae was discovered in the wall of the cemetery of Brison-Saint-Innocent. It reads: Dominis, exs voto [v(otum)] s(olvit) l(ibens) m(erito), Marcus Carminius Magnus pro salute sua et suorum, ‘To the Dominae, Marcus Carminius Magnus, paid his vow willingly and deservedly, for his salvation and (that of) his family’ (fig. 9).2344 The dedicator has Latin names and bears the tria nomina of Roman citizens. In Latin, the word domina refers to the woman in charge of the domestic aspects and means ‘housewife’ or ‘mother’, as well as ‘ruler’ or ‘sovereign’. It is an epithet expressing affection and profound respect, usually employed for a queen or a housewife. The Dominae are thus the ‘Rulers’ or ‘Sovereigns’, which directly links them to the Comedovae. Lambert explains that their name is certainly the Latin translation of the Gaulish theonym Comedovae.2345 This translation process, which aimed at replacing the names of indigenous deities by Latin names of the same meaning, is attested in other parts of Gaul and has been studied by Fleuriot.2346 Lambert adds that the Dominae are very likely to be the same divine figures as the Comedovae, because the two stones are of same style and dimension, and come from the same stone carving worshop.

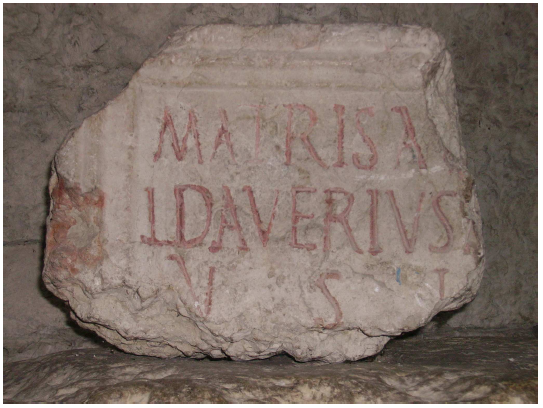

The inscription dedicated to the Matrae, probably dating from 2nd c. AD, was discovered in 1866 in the steeple of the Church of Saint-Innocent. It reads: Matris Au[gustis], L. Daverius […] v(otum) s(olvit) l(ibens) [m(erito)], ‘To the August Mother Goddesses, Lucius Daverius […] paid his vow willingly and deservedly’ (fig. 10).2347 The dedicator has Latin names and is a Roman citizen, for he bears the duo or tria nomina. As explained in Chapter 1, an epithet, endowing the mothers with a specific location, status or function, was often attached to the title Matrae or Matronae, such as in Moutiers, where a dedication to the Matronae Salvennae have been unearthed.2348 As a consequence, Comedovae could be envisaged as the epithet of the Matrae revered on that very inscription, giving Matrae Comedovae.2349 Therefore, Comedovae, Dominae and Matrae are certainly different names used to refer to the same mother goddesses.